A 2016 paper has been retracted at the request of a company that provides geoscience solutions because the authors—who are employees of the company—included proprietary information and didn’t obtain proper permission.

A 2016 paper has been retracted at the request of a company that provides geoscience solutions because the authors—who are employees of the company—included proprietary information and didn’t obtain proper permission.

Often in extenuating circumstances such as publishing something without permission, the article is taken offline. But this article, which according to the retraction notice “contains information, data and intellectual property belonging to the company and its client,” remains available. What’s more, the authors seem to think they had the company’s okay to publish.

Here’s the complete retraction notice for “High resolution seismic imaging of complex structures: a case study of the South China Sea data” published by Marine Geophysical Research:

Continue reading Geoscience paper pulled over apparent lack of company consent

Around two years ago, when mathematics researcher

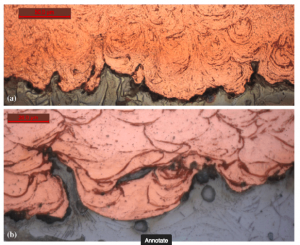

Around two years ago, when mathematics researcher  A pathology journal is retracting two papers after an investigation at the last author’s institution in Germany found evidence of scientific misconduct.

A pathology journal is retracting two papers after an investigation at the last author’s institution in Germany found evidence of scientific misconduct.