How common are calculation errors in the scientific literature? And can they be caught by an algorithm? James Heathers and Nick Brown came up with two methods — GRIM and SPRITE — to find such mistakes. And a 2017 study of which we just became aware offers another approach.

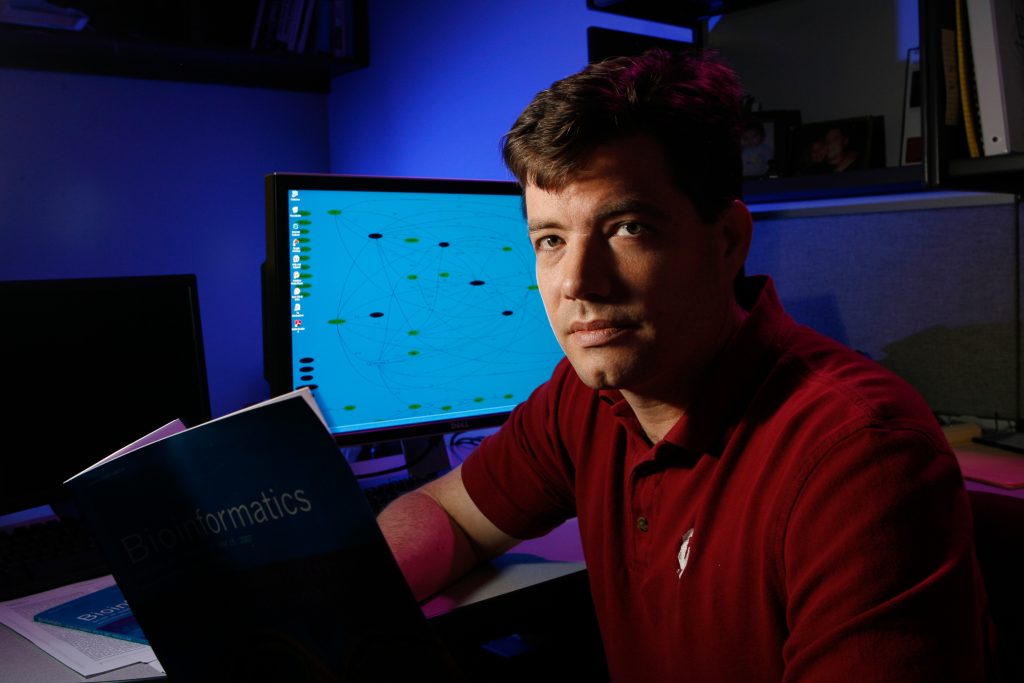

Jonathan Wren and Constantin Georgescu of the Oklahoma Medical Research Foundation used an algorithmic approach to mine abstracts on MEDLINE for statistical ratios (e.g., hazard or odds ratios), as well as their associated confidence intervals and p-values. They analyzed whether these calculations were compatible with each other. (Wren’s PhD advisor, Skip Garner, is also known for creating such algorithms, to spot duplications.)

After analyzing almost half a million such figures, the authors found that up to 7.5% were discrepant and likely represented calculation errors. When they examined p-values, they found that 1.44% of the total would have altered the study’s conclusion (i.e., changed significance) if they had been performed correctly.

We asked Wren — who says he thinks automatic scientific error-checkers will one day be as common as automatic spell-checkers are now — to answer a few questions about his paper’s approach. This Q&A has been slightly edited for clarity.

Retraction Watch (RW): What prompted you to perform your study? Continue reading Will scientific error checkers become as ubiquitous as spell-checkers?

Sometimes, corrections are so extensive, they can only be called one thing: Mega-corrections.

Sometimes, corrections are so extensive, they can only be called one thing: Mega-corrections. The authors of a 2018 paper on how noisy distractions disrupt memory are retracting the article after finding a flaw in their study.

The authors of a 2018 paper on how noisy distractions disrupt memory are retracting the article after finding a flaw in their study.  In March, a journal published a paper about blood sugar levels in newborns that caused an immediate outcry from outside experts, who were concerned it contained a sentence that could be potentially harmful if misinterpreted by doctors.

In March, a journal published a paper about blood sugar levels in newborns that caused an immediate outcry from outside experts, who were concerned it contained a sentence that could be potentially harmful if misinterpreted by doctors.  The New England Journal of Medicine has retracted a 2013 paper that provided some proof that the Mediterranean diet can directly prevent heart attacks, stroke, and other cardiovascular problems.

The New England Journal of Medicine has retracted a 2013 paper that provided some proof that the Mediterranean diet can directly prevent heart attacks, stroke, and other cardiovascular problems. Six months ago, the media was ablaze with the findings of a new paper, showing that nearly six percent of cancer cases are caused, at least in part, by obesity and diabetes. But this week, the journal retracted that paper — and replaced it with a revised version.

Six months ago, the media was ablaze with the findings of a new paper, showing that nearly six percent of cancer cases are caused, at least in part, by obesity and diabetes. But this week, the journal retracted that paper — and replaced it with a revised version.

Here’s something we don’t see that often — authors retracting one of their articles because it included new data.

Here’s something we don’t see that often — authors retracting one of their articles because it included new data.