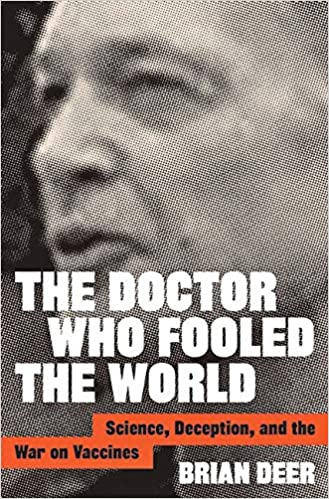

Retraction Watch readers are no doubt familiar with the case of Andrew Wakefield, the former gastroenterologist who led a 1998 paper in The Lancet — now retracted — that led him to claim a link between the MMR vaccine and autism. It was journalist Brian Deer who revealed the true details of that work, and in this excerpt from his new book, The Doctor Who Fooled the World, released today in the U.S., Deer reports on Wakefield’s formative years.

In some imaginary universe, he might be revered as Professor Sir Andrew Wakefield. Two decades before his invitation to Donald Trump’s inauguration ball, the destination he felt beckoned, like a big bony finger, wasn’t in Washington, DC, or anywhere in America, but a concert hall in downtown Stockholm. Dressed like Fred Astaire in white tie and tails, his dream, people said, was to collect a gold medal from the hands of the King of the Swedes.

“You’d hear them in the canteen,” a former colleague of his tells me. “They’d be talking about the Nobel Prize.”

But to that, or any, universe, the gateway was the same: the portal to all his possibilities. It stood then—and stands now—on Beacon Hill: high above the city of Bath, in the county of Somerset, ninety minutes by train west of London. Here you’ll find the entrance to his childhood home, and the exit to all roads he will travel.

It’s no picket gate. This isn’t Tom Sawyer. I’d guess the frame weighs more than a ton. Embracing two ten-foot Doric columns and matching pilasters, with an ornately carved frieze across a multilayered architrave, it resembles the entrance to a Victorian mausoleum, or a side door to the Colosseum of Rome. It speaks of wealth, class, authority, and entitlement. In uppercase, the lintel is lettered:

Continue reading The Doctor Who Fooled The World: An excerpt from Brian Deer’s new book about Andrew Wakefield