M.A. Oviedo-Garcia et al/medRxiv 2025

A network of peer reviewers in Italy is targeting medical journals, threatening “both the scientific record and patient safety,” a team of researchers report. Without more transparency by journals, they say, most review mills will remain impossible to detect.

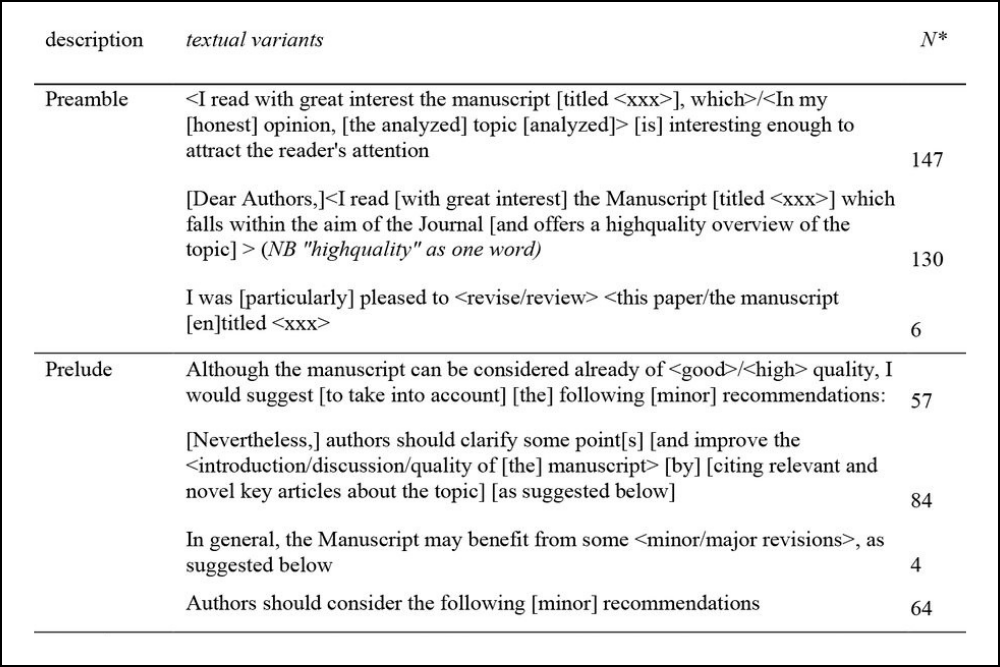

In a preprint posted on medRxiv on October 23, sleuths Dorothy Bishop, René Aquarius and Maria Ángeles Oviedo-García say they discovered the alleged review mill when they stumbled upon seemingly “boilerplate” comments in a peer review. This discovery led the trio to search for published peer reviews that shared similar terminology — work that ultimately identified 195 suspect reviews of 170 articles published between Feb. 6, 2019, and July 7, 2025. The researchers speculate the number of articles affected is likely higher given most journals do not publish their peer reviews.

The alleged mill is run by “well-established, Italian physicians in the fields of gynecology and oncology,” wrote the authors of the new study, which also noted the reviewers were refereeing papers with clinical implications, a pattern the authors called “alarming.”

Continue reading Review mill in Italy targeting ob-gyn journals, researchers allege

Peer reviewers, like authors, are supposed to

Peer reviewers, like authors, are supposed to