Ever wanted to hone your skills as a scientific sleuth? Now’s your chance.

Thanks to the American Society for Biochemistry and Molecular Biology (ASBMB), which is committed to educating authors on best practices in publishing, figure preparation, and reproducibility, we’re presenting the twelfth in a series, Forensics Friday.

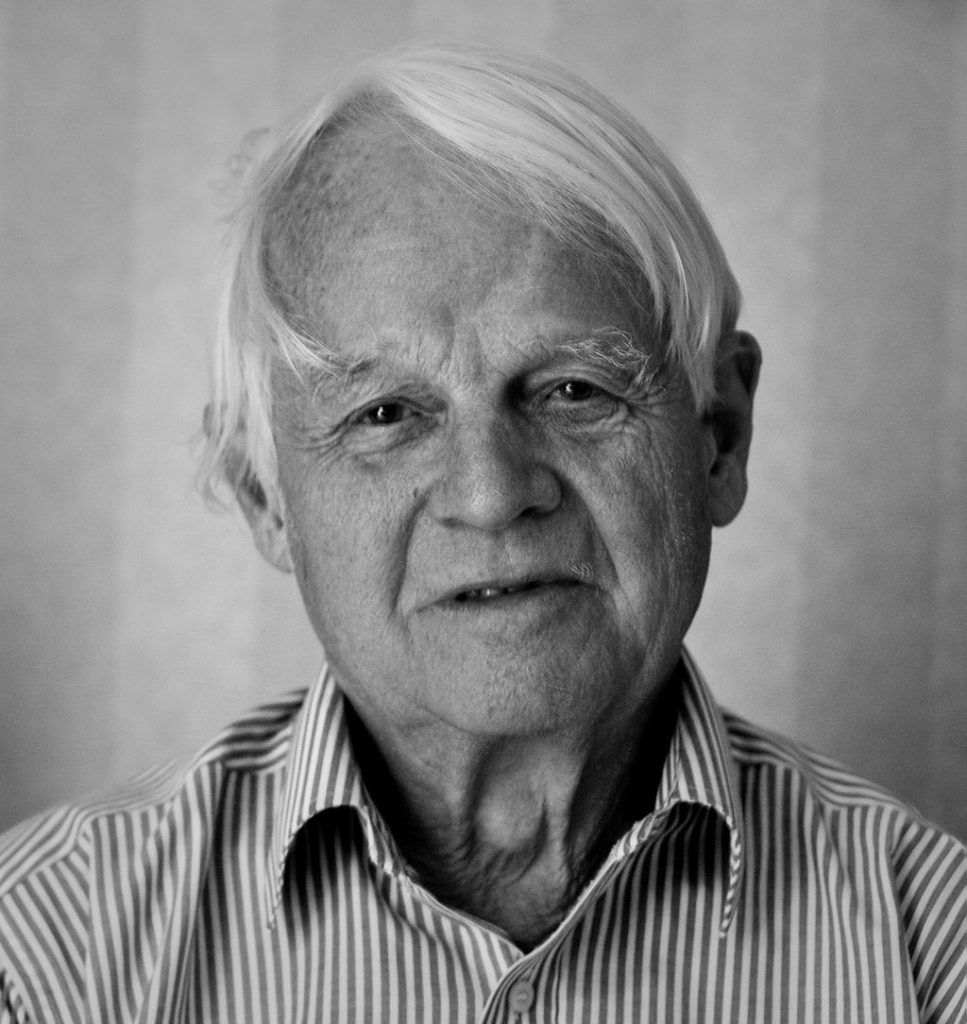

Take a look at the image below, and then take our poll. (We recommend using the Chrome browser.) After that, click on the link below to find out the right answer.

Continue reading Forensics Friday: You’re the reviewer. What do you recommend for this panel?