Would you consider a donation to support Weekend Reads, and our daily work?

The week at Retraction Watch featured:

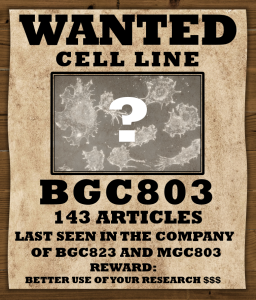

- Misspelled cell lines take on new lives — and why that’s bad for the scientific literature

- Journal blacklists doctor in Pakistan ‘out of an abundance of caution’

- Up to one in seven submissions to hundreds of Wiley journals flagged by new paper mill tool

- Rejected paper pops up elsewhere after one journal suspected manipulation

Our list of retracted or withdrawn COVID-19 papers is up past 400. There are more than 47,000 retractions in The Retraction Watch Database — which is now part of Crossref. The Retraction Watch Hijacked Journal Checker now contains more than 250 titles. And have you seen our leaderboard of authors with the most retractions lately — or our list of top 10 most highly cited retracted papers? What about The Retraction Watch Mass Resignations List?

Here’s what was happening elsewhere (some of these items may be paywalled, metered access, or require free registration to read):

Continue reading Weekend reads: A paper written by ChatGPT goes viral; the Gino misconduct investigation report; superconductivity scandal