Pro tip to would-be fraudsters: If you’re going to submit new figures to support your claims, make sure they’re not obviously fake.

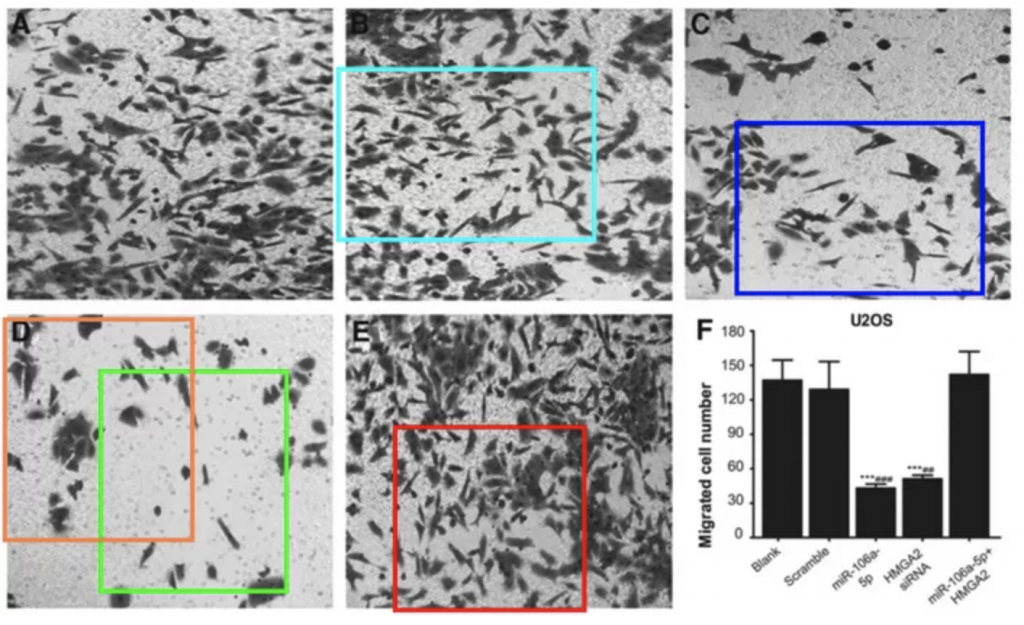

That’s a lesson a group of cancer researchers learned the hard way for their 2016 article in DNA and Cell Biology titled “miR-106a-5p suppresses the proliferation, migration, and invasion of osteosarcoma cells by targeting HMGA2.” The corresponding author was Fang Ji, of The Second Military Medical University in Shanghai.

The paper appeared on PubPeer earlier this year, where a commentor noted dryly:

Continue reading Researchers tried to correct a figure after questions on PubPeer. Then the real trouble started.