[This post has been updated since publication; see update note at end for details.]

In July 2019, Kevin Hall, of the U.S. National Institutes of Health, and colleagues published a study in Cell Metabolism that found, according to its title, that “Ultra-Processed Diets Cause Excess Calorie Intake and Weight Gain.”

A year and a half after its publication, the paper is the subject of two critical blog posts, one by Nick Brown and one by Ethan and Sarah Ludwin-Peery. In the days since we first shared embargoed drafts of those posts with Hall, he and the sleuths engaged in a back and forth, and Brown and the Ludwin-Peerys now say they are satisfied that many of the major issues appear to have been resolved. They have also made changes to their posts, including adding responses from Hall.

In short, it seems like a great example of public post-publication peer review in action. For example, the Ludwin-Peerys write:

When we took a close look at these data, we originally found a number of patterns that we were unable to explain. Having communicated with the authors, we now think that while there are some strange choices in their analysis, most of these patterns can be explained…

In a draft of their post shared with us early last week — see “a note to readers” below — the Ludwin-Peerys said that some of the data in the study “really bothered” them. In particular, they write, the two groups of people studied — 20 received ultra-processed foods, while 20 were given an unprocessed diet — “report the same amount of change in body weight, the only difference being that one group gained weight and the other group lost it.” They were also surprised by the “pretty huge” correlation between weight changes and energy intake.

Brown’s draft post, which digs into the data, concludes:

Hall et al.’s article seems to have had a substantial impact on the field of nutrition research. However, both Ethan & Sarah’s post and this one raise a number of concerning questions about the reliability of this study. There seem to be problems with the design, the data collection process, and the analyses. I only looked at about half of the 23 data files, so there may be other problems lurking. I hope that the authors and the editors of Cell Metabolism will take another look at this study and perhaps consider issuing a correction of some kind.

In a document we’ve uploaded here, Hall responded point-by-point to a draft of Brown’s post we shared with him last week week (see “a note to readers”):

As previously noted, a correction was issued in October of 2020 regarding an error that we independently discovered. Many of the other questions raised above are the result of misinterpretations of the data and we hope that we have now clarified these issues. Several remaining questions have been raised that we have yet to be able to address due to the limited amount of time provided because the authors of the blogs wanted to publish without allowing us the opportunity to fully respond.

We’d suggest reading both Brown’s and the Ludwin-Peerys’ updated posts in full.

Hall also sent these comments about the draft of the Ludwin-Peerys’ post we sent him:

[T]hey begin by noting some data reported in the abstract that “really bothered” them. In particular they note that it is unlikely for the reported standard errors to be the same for the weight changes during the two diet periods. A similar concern was raised in the online Comments section of the Cell Metabolism publication, where another researcher noticed equal reported SEMs between the groups. We replied with the following explanation:

As described in the Quantitative and Statistical Analysis section, we used the general linear model (GLM) procedure as implemented in SAS to analyze the data and we reported the least square means and standard errors. One of the common assumptions of the GLM procedure is the homogeneity of variances between groups and therefore it should not come as a surprise that the reported least square mean and standard errors have equivalent standard errors between groups when N is identical. Differing reported standard errors in the Tables occurred in the rare instances of missing data.

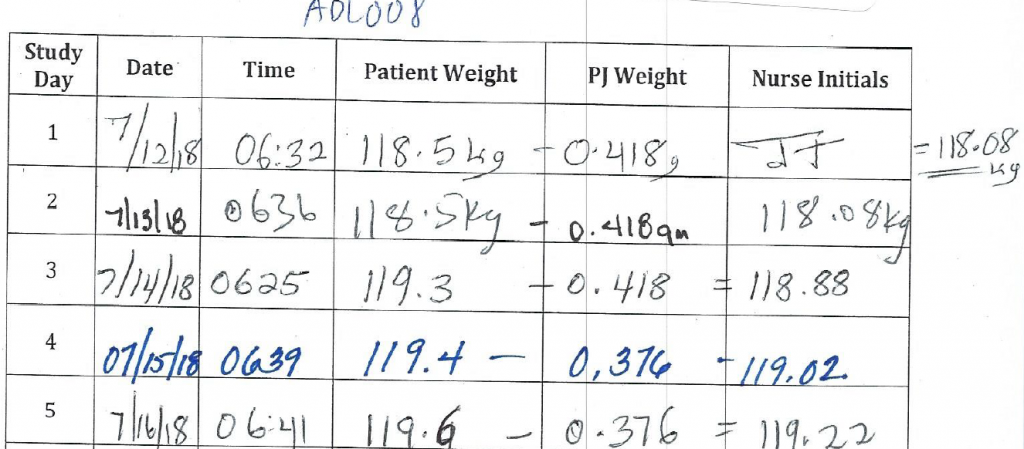

Much of the rest of the blog by Ethan and Sarah Ludwin-Peery involves the body weight measurements in our study and the apparently implausible precision of these measurements and the improbable frequency distribution of the trailing x digits in the reported 0.0x and 0.00x kg body weight measurements. While we have not addressed every single instance in the subsequent ~10 pages of analysis, the explanation appears to be rather straightforward. The Method Details section of the manuscript states that “Daily body weight measurements were performed at 6am each morning after the first void (Welch Allyn Scale-Tronix 5702; Skaneateles Falls, NY, USA). Subjects wore hospital-issued top and bottom pajamas which were pre-weighed and deducted from scale weight.”

Below is an excerpt from the body weight log of one example subject ADL008 who was weighed to 0.1 kg precision in their pajamas (PJ) whose weight was subtracted resulting in an apparent body weight of high precision. Because the same PJs were worn for multiple days during the weigh in, the trailing high precision digits repeat in a manner that is not random. In this example below, the same PJs were worn on days 1-3 and then new PJs were worn on days 4 and 5.

It should also be pointed out that the pre-specified primary aim of the study was to measure differences in mean ad libitum energy intake between the diet periods. Thus, it is misleading for these blog authors to claim that “weight change is the primary dependent variable for this study”. The clinical protocol available on the OSF website states that body weight and composition changes were the third exploratory aim of the study.

I hope that our response helps clarify much of the confusion expressed by the authors of these blogs. We will continue to work to provide answers to the other questions raised that we have not yet had time to address.

Update, 0140 UTC, 1/23/21: Following the publication of this post, Hall sent us an updated response to the two blog posts. Brown updated his post, as well:

Update 2021-01-22 23:21 UTC: I have received an extensive response from Kevin Hall, the lead author of the study under discussion here. This addresses the great majority of the points that I raised in this post. I will attempt to incorporate a version of those responses in a forthcoming update, but I wanted to get this acknowledgement of that response out there as soon as possible.

Ethan Ludwin-Peery also tweeted:

A note to readers

For transparency, we should provide some background on how we reported on this story. In late December, Ethan Ludwin-Peery contacted us to say that he and colleagues had found potential problems in the paper, and asked for our advice. We told him that, for reasons described in our FAQ, we can’t give advice, but would be happy to take a look to see if there was a potential story for us to cover. We also asked if we could send his analysis to other experts for their opinion.

Ethan Ludwin-Peery agreed, and we forwarded his notes to Brown and James Heathers, two “data thugs” whose names will likely be familiar to Retraction Watch readers. Since we considered this a potential story, we asked that we be given the opportunity to report on it. Brown began taking a look, and asked if he could contact Ludwin-Peery, which was fine with Ludwin-Peery. Late last week, Brown said he was basically done with his analysis, a draft of which he sent us, and Ludwin-Peery sent us his — which Brown’s post suggests readers look at first — on Monday. They said they planned to post them both this week, likely today.

We explained that we would need to share them with Hall for his response before we were able to publish, which they were fine with, so first thing Tuesday morning we sent both draft posts to Hall for comment. He responded right away, and we had an exchange over a few days in which he shared his findings as he reviewed the critiques. We shared many of those with Brown and Ludwin-Peery for their response, and they said they were considering incorporating some of them in their posts.

Given the deadline of today’s posts to respond, Hall pointed out that yesterday was a U.S. federal holiday (the Presidential inauguration) and said that his response would be even more full sometime next week, after a key staff member had undergone a scheduled procedure. We relayed these points to Brown and Ludwin-Peery, who said they wanted to stick to their original plan of posting today, and we’re posting this now to coincide with those posts and to provide Hall a chance to respond at the same time. Brown and Ludwin-Peery both felt that it was best if these kinds of discussions happened in public, and while we agree, we also feel it’s important to give researchers a reasonable chance to respond. “It is disappointing that the authors of these blog posts are unwilling to wait for us to be able to fully respond to the issues raised,” Hall told us.

We will continue to follow the story.

Update, 1430 UTC, 1/29/21: In addition to the updates marked in the text above, the headline of this post has been changed to note Hall’s responses, and material has been moved into a new second paragraph to reflect this evolving story.

Like Retraction Watch? You can make a tax-deductible contribution to support our work, follow us on Twitter, like us on Facebook, add us to your RSS reader, or subscribe to our daily digest. If you find a retraction that’s not in our database, you can let us know here. For comments or feedback, email us at [email protected].

My memory of using significant figures is that you can’t substract a more precise measurement from a less precise measurement and make the less precise measurement more precise. So, the final number should only have been calculated/rounded to a single decimal point; not to 2 decimal points.

When I was doing A-level science, we were issued with a “data sheet” that had among other things are list of melting and boiling points of certain substances. The syllabus had recently gone over to SI units, so the temperatures were all in Kelvin. It was noticeable that although they were all given to two decimal places, the figures after the point were always either .15 or .65. In other words, it was originally a list given to the nearest half degree Centigrade, with 273.15 added to everything.

When I see terms like ultra-processed, I get that tingle that tells me I’m dealing with someone I can’t trust. My first hit on a search for the definition of the term – https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6389637/

gives me this: “there is little consistency either in the definition of ultra-processed foods or in examples of foods within this category.”

‘Ultra-processed’ food goes with ‘Big’ oil, and ‘Big’ pharma, and any other enemy speech of the day. ‘Ultra’ is not a technical term in nutrition science – assuming there is any such thing as a contemporary ‘science’ of nutrition worth the name.

“I only looked at about half of the 23 data files”

Wow, nothing says “in-depth investigation” like only looking at half of the data. I think Nick and friends are making a mountain out of a molehill. The significant figures thing is a bit silly, but doesn’t invalidate the findings at all–just round to the nearest integer when assessing the final results, like any normal person would do. Actually, I remember being told in high school not to round until the very end, so the authors probably did the right thing by sharing the “full precision” raw data, even if the last few digits are a bit spurious.

This RW post completely lacks journalist integrity. It links to 2 “must read” blog posts, as if these “data thugs” have discovered some treasure trove of critical errors and inconsistencies in Dr. Hall’s work (plot twist: turns out they didn’t). More bizarrely, although the paper in question was published in *July 2019*, and the bloggers had contacted RW about this paper in DECEMBER, there becomes this sudden urgency to post their allegations on the seemingly arbitrary date of Jan 21. Per the “Note to readers” account, the bloggers will not wait for KHall to respond in full, despite his immediate and reasonable request for a few more days. Was it a total coincidence that the sudden rush to post on Jan 21 also happened to be the embargo date for KHall’s next high-profile feeding trial results being published in Nature Medicine? Why couldn’t a post about an 18 month old study wait a few more days to be thoroughly verified by RW before endorsing its contents on their far-reaching platform? Very sloppy Ivan Oransky. Even sloppier, many of the blogger’s issues that “really bothered” are easily resolved by actually reading the paper or having some subject matter knowledge. So now KHall has responded in full, point-by-point, wasting God knows how many tax-payer dollars (he’s a NIH employee) to point all of this out. RW – how about you take this post down until it can be re-written with more integrity. Retracting erroneous investigation is the mission of this website after all.

wasted almost as many tax-payer dollars as the study itself! lol

While I am a fan of “data thugs” and have absolutely no problem with them investigating this researcher’s work based on what appeared to be some weird-looking data, I do agree that this matter could have been better handled privately with the author, or at least could have been posted after all responses from the author were received. In fact, I think this could have been presented as sort of a case study demonstrating that sometimes weird-looking data make perfect sense once you look further into it. As Hall mentions in one of his responses, the limitations of details that can be included in a Methods section can lead to confusion or incorrect assumptions (e.g., the pajama situation). Data that are fairly improbable (e.g., having the same magnitude of mean and SE for change in weight in both conditions) aren’t impossible.

I have no information or understanding regarding the particular timing of the blogs and how it was related to an embargo date, so I don’t know whether that was done in bad faith. But I do think it was bad practice to not have given Dr. Hall a chance to fully respond to the seeming data anomalies rather than shooting first and asking questions later.

With respect to RW, I don’t think they did anything wrong. They didn’t use a clickbaity headline…they descriptively reported that that a paper was being examined, with no statement indicating that the paper was flawed. They published Dr. Hall’s responses. I guess to some extent anything published in this blog comes with an assumption that something is wrong. I’m not an expert on journalistic ethics, but I think Ivan has been doing excellent work for a long time, and so I give him the benefit of the doubt that there is nothing untoward here.

So in the end, I don’t doubt anyone’s motives, but I think the situation could have been handled much better to be fair to Dr. Hall. But, hopefully everyone learned something from this that can be used to do better going forward.

You don’t seem to understand the statement, “In short, it seems like a great example of public post-publication peer review in action.”

It’s very clear early on this isn’t some sort of take down but a case where some data that looks suspicious was cleared up through an open peer review. Maybe you don’t think it’s such a great example of such review but your comment doesn’t reflect that.

Aaron, I appreciate the incisive analyses and tactfulness of your posts.

Given the unknown contamination sources, lack of disclosure for experimental substances, and non-transparent procedures, the Hall study produced nothing but noisy data that defies replication and certainly does not imply causation.

Noise is inevitable in most human investigations, but it’s unacceptable not to take some basic, obvious measures to reduce the cacophony.

A lot of money and effort was squandered on an investigation that was sloppy both in design/execution and reflected a lack of scientific understanding of the basic issues of the science.

For details, please see: https://www.stealthsyndromesstudy.com/?p=2610

I’m not sure they could have avoided it being a noisy study without changing the N substantially.

They could have avoided writing it up like it was the definitive study on the matter regardless.