Background factors such as culture, location, population, or time of day affect the success rates of replication experiments, a new study suggests.

Background factors such as culture, location, population, or time of day affect the success rates of replication experiments, a new study suggests.

The study, published today in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, used data from the psychology replication project, which found only 39 out of 100 experiments live up to their original claims. The authors conclude that more “contextually sensitive” papers — those whose background factors are more likely to affect their replicability — are slightly less likely to be reproduced successfully.

They summarize their results in the paper:

…contextual sensitivity was negatively correlated with the success of the replication attempt…

The authors note:

Although the notion that “context matters” is informally acknowledged by most scientists, making this common sense assumption explicit is important because the issue is fundamental to most research.

First, three researchers with graduate training in psychology rated the 100 psychology experiments from the replication project by how much their results could be influenced by their context. Blind to whether or not a study had been replicated, the coders looked out for the

time (e.g., pre vs. post-Recession), culture (e.g., individualistic vs. collectivistic culture), location (e.g., rural vs. urban setting), or population (e.g., a racially diverse population vs. a predominantly White population).

For example, an experiment carried out in a certain country at a specific time of year by people from a certain set of beliefs, practices, or values may only be reproduced successfully within those conditions.

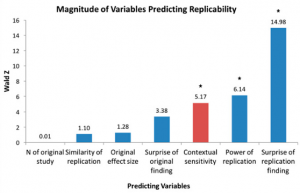

The authors then compared the likelihood of replication to the rate at which studies relied on their context, along with other possible variables, such as whether the original findings were surprising. Here’s a graph from the paper, which shows the context of the papers to be the third biggest contributor to replication success:

Lead author of the study, Jay Van Bavel, an assistant professor of social psychology at New York University, told us the results suggest that the study’s context was important to the success of its replication in a “small to moderate effect size.”

He added:

The raters were blind to the results and the design of the replication studies, which helped mitigate any bias that might have affected our results. This was an important feature of our study. I should also add that all the raters have previously worked in labs in social and cognitive psychology, so they had expertise that covered many of the topics in the Reproducibility Project. Moreover, we went through a rigorous process to ensure high inter-rater reliability prior to rating the entire set of studies.

Van Bavel went on to say that the debate around context in replication studies — or “hidden moderators” — is a “contentious” one:

We are in a bit of a quagmire. I’m a big fan of replication — [but] we need to find ways to make it easier for others to replicate our work to (a) ensure it is robust and (b) identify new boundary conditions. We are on the right track in terms of advocating for larger samples, greater transparency, and superior methods. But we can’t lose [sight] of theoretical frameworks that outline when an effect should occur and when it should not. In my view, the original authors should be more explicit about some of these boundary conditions and the replicators should be receptive to any insights the original authors might have to share about these issues.

When asked about the limitations of his paper, Van Bavel said:

Most of our limitations were redundant with the limitations of the Reproducibility Project itself — we were limited to 100 studies, some of the replications were contentious, and the co-variates were not exhaustive. As the corpus of replication studies grows, it would be fantastic to replicate our own analysis.

But Brian Nosek, a professor of the psychology at the University of Virginia who-coauthored the original psychology reproducibility paper, said he isn’t convinced that there is an influence of “context sensitivity:”

…the present study doesn’t unambiguously indicate a causal role of context sensitivity on reproducibility for two major reasons:

(1) Causal inference from correlational data is difficult. There is always the possibility that ratings of context sensitivity correlate with another variable that is actually the operative cause of the relationship. Nonetheless, they did a nice job of developing some evidence with what was available.

(2) The measure of context sensitivity was raters predictions of context sensitivity, not actual assessment of context sensitivity. It is possible that the raters have good, accurate theories about context sensitivity. It is also possible that raters’ assessments of context sensitivity assess things besides actual context sensitivity.

Gary King, a statistician and social scientist at Harvard University who co-authored a recent technical comment in Science criticizing the psychology reproducibility project (to which Nosek responded on our site), told us he agreed that the influence of context sensitivity seems “weak:”

The authors report that the correlation between replicability and contextual sensitivity is -.23. Is this big? Actually, to me it is surprisingly weak. It is in the expected direction, but I would have guessed it was higher.

King noted that it would be useful to know exactly what the authors mean by different levels (1-5) of contextual sensitivity, adding:

The authors gave it a good try, but it is very difficult with the way they operationalized this to even convey what was being measured, except at a very general level. This is not their fault, as it is clear that there is such a thing as contextual sensitivity but the 100 studies (which are observations in their analysis) are tremendously diverse and they were trying to come up with one measure that spanned them all.

King continued:

…it is crucial to not declare ‘lack of replicability’ by one author as some type of failure. The replicator doesn’t have the role of judge; it is merely a second scientific study, conducted under somewhat different circumstances. Random variabil[i]ty will explain some of the differences in results, context in others. The goal of the scientific process is to parse out which is which.

Psychologists deserve credit for taking an empirical approach to factors that lead to successful replications, said Van Bavel. And the problem of contextual factors is not limited to psychology, he added — even experiments on mice and slime moulds are riddled with some contextual limitations, which is a “natural part of science.” Van Bavel concluded:

We need to invest more time digging into these issues to understand exactly why certain effects replicate in one lab and not another. We can certainly weed out work that isn’t replicable, but we should also keep an eye toward building better theories to understand why we get effects in some contexts but not in others.

Like Retraction Watch? Consider making a tax-deductible contribution to support our growth. You can also follow us on Twitter, like us on Facebook, add us to your RSS reader, sign up on our homepage for an email every time there’s a new post, or subscribe to our new daily digest. Click here to review our Comments Policy. For a sneak peek at what we’re working on, click here.

I propose that Retraction Watch formally adopt the “best practice” standards of science and make available full “replication data sets” (e.g., King, 1995) for each of the articles they write here. I was quoted in this particular article (by Dalmeet Singh Chawla) and so have an unusual view into their journalistic practices. My own view is that the quotes Chawla selected from the longer email I sent were completely appropriate, and the article was well done, but of course any summary of information is necessarily biased against everything omitted that doesn’t exactly represent what was included. Chawla chose, by some set of unstated rules, to present some points I (and the others he interviewed) made and not others. Retraction Watch, just like any scientist summarizing data, should provide full information about the complete chain of evidence from the world, and the process by which it is distilled down to the article presented. In most cases like this, this information should include the people he tried to interview, how these people were chosen, the smaller sample of those who actually were interviewed (and the implied nonresponse rates, and likely biases induced by the particular pattern of nonresponse), all notes and emails from the conversation summarized in the article or omitted entirely, and all other information that might help a third party reproduce the substantive conclusions of the Retraction Watch article from the evidence gathered. If others disagree with the distillation process, or the conclusions, they ought to have the full chain of evidence to decide for themselves or make a different case.

One possible objection to my suggestion is that different standards apply to journalists, but in my view this is an unreasonable position. The authors of Retraction Watch are making well defined empirical claims — ones with career making and breaking consequences for individuals, and sometimes huge cross-discipline-wide impacts — on the basis of a wide variety of quantitative and qualitative data. There’s no reason why the community of those interested in this question shouldn’t have access to these data to improve inferences we all make from it; if the standards were followed, Retraction Watch and its readers would benefit just as much as when the scientific community has access to data to improve its conclusions. The community they built will then help them improve Retraction Watch even more.

Another possible answer to my suggestion is that Retraction Watch aims to publish immediately, without peer review, on a much faster timetable than is possible with the usual scientific article. This is true but doesn’t move their conclusions outside the realm of science, or scientific standards. After all, a scientific statement is not one that is necessarily accurate; it is a statement that comes with an honest estimate of uncertainty. If they publish fast, without full information, they are more uncertain and need to (and often do) express that. There’s nothing unscientific about choosing to go to press early under those circumstances. What they are doing is exactly scientific inference — or using facts they have to learn about facts they don’t have — and so the same standards for how to do this well applies as to ordinary scientific articles. If we want to get the story as right as possible, then they should be following the same standards as the best scientists. This would be unusual (although not remotely unheard of) among journalists, but Retraction Watch should lead the way in journalism as they have in reporting about retractions.

A final objection is privacy and other human subjects rules. This of course is something with which social scientists have long experience, and all the protections and procedures necessary. There are archives (such as dataverse.org, which we’ve developed at IQSS) which will be happy to permanently archive the data behind Retraction Watch articles and distribute it to only those who have signed the appropriate licensing agreements or received appropriate approvals.

Gary King

Institute for Quantitative Social Science

Harvard University

GKing.Harvard.edu

Reference

Gary King. 1995. “Replication, Replication.” PS: Political Science and Politics, 28: 444-452, September. Copy at http://j.mp/jCyfF1