I first became aware of the work of Drummond Rennie almost by accident: By borrowing his office. It was the summer of 1997, and as a rising fourth-year medical student, I was spending a month at JAMA as the co-editor-in-chief of its then-medical student section, Pulse. Rennie, who was deputy editor of the journal at the time, was mostly traveling, so the staff installed me in his office, overflowing with books and manuscripts.

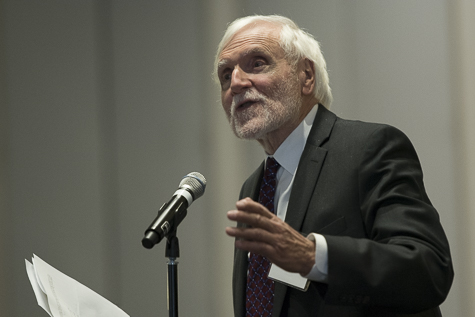

Rennie, who died on September 12, was a towering figure in scientific publishing. Trained as a nephrologist, he joined the staff of the New England Journal of Medicine in 1977, and later, JAMA, where he remained for decades. He was known for promoting improved standards in medical journals, and for organizing the first Peer Review Congress, held in 1989 and nine more times since, most recently earlier this month.

In 2013, we were just a few years into the work of Retraction Watch, and thought talking about what we’d learned so far at the Congress would be a good idea. We submitted an abstract outlining what we wanted to talk about, writing that we’d gather data by the time of the meeting.

Continue reading Drummond Rennie (1936-2025), in his own words