A team of researchers in Belgium got more than they expected when they tried to study potato pathogens: an unwelcome contaminant, a retraction, and a new paper the authors say is “an improvement over the first.”

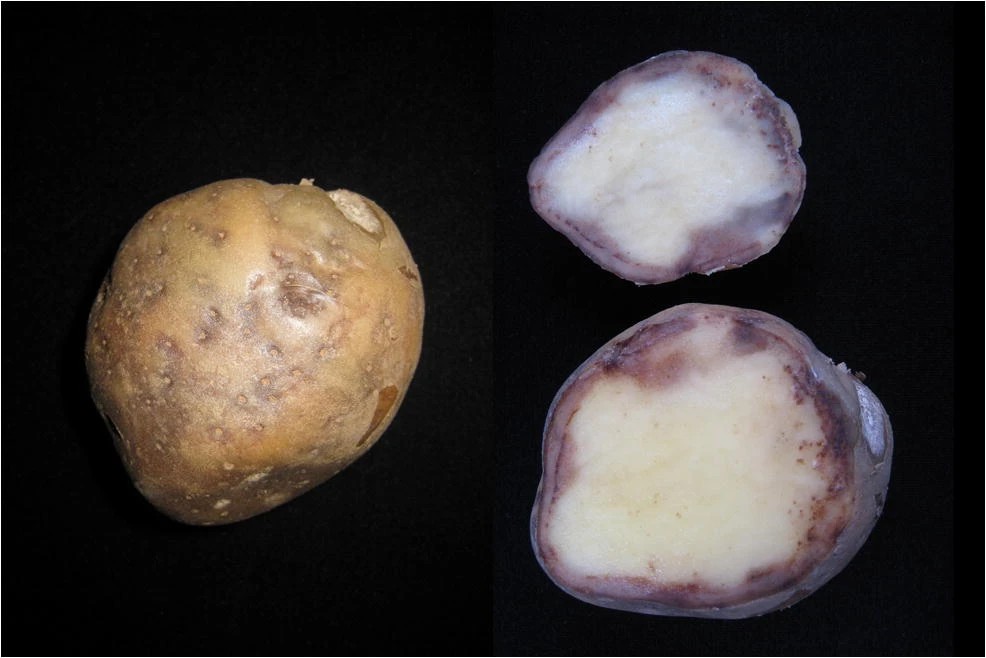

In a now-retracted paper in Metallomics originally published in January 2024, researchers at the University of Liège described how availability of nitrogen and iron changes how the bacterium responsible for potato common scab interacts with each of the two microorganisms responsible for early and late blight while infecting the same host. The results suggested the bacterium had antimicrobial properties against both microbes, with nearly all of the experiments focusing on the fungus that causes late blight.

After publication, the authors realized their strain of the late blight-causing microorganism was not the one described in the paper. While the lab originally received the correct strain, “the plates became contaminated, and the fungal contaminant eventually overgrew the strain we intended to study,” Sébastien Rigali, corresponding author and professor at the University of Liège, told Retraction Watch.

Sample contamination in the lab is an ever-present problem for researchers and has led to the retraction of multiple papers. For studies using cell lines, resources such as the ICLAC Register of Misidentified Cell Lines and Research Resource Identifiers can help scientists prevent the use of tainted cells. Fungal contamination during preparation and experiments is such a common problem that many cell culture guidelines include a section on how to handle it.

For the fungus cultures used in the Metallomics study, genome sequencing confirmed the actual strain wasn’t the one described in the paper. “Because our work focused on macroscopic phenotypes, we did not initially notice the contamination; the original strain and the contaminant looked similar on Petri dishes,” Rigali told us in an email. Later, he examined the samples using electron microscopy and “realized the morphology was not as expected.”

He and his collaborators contacted the journal to request the retraction of the paper, as “the data themselves were scientifically sound, but the biological narrative was wrong because we were unknowingly working with an unintended organism.”

“Even with great care and the best working conditions, mistakes can still occur,” said Rigali. “What would have been far worse is failing to detect the contamination and allowing an incorrect story to remain published.”

The paper was retracted in April 2024, less than four months after its publication.

“All collaborators responded unanimously that ‘these things happen,’ emphasizing that what truly mattered was that we retracted the paper almost immediately after publication and submitted a revised version, which we all agree is an improvement over the first,” Rigali said.

The replacement paper was published in Metallomics in October 2024. The retraction notice was updated in November 2025 to note the replacement, “which now accurately refers to the correct strain,” the notice states. The new paper’s “objectives and context are properly aligned and more focused on specific environmental nutrients that trigger the antifungal activity of Streptomyces scabiei”— the potato scab-causing bacteria — “through iron deprivation.”

Often the retraction, replacement, and notice are published simultaneously in cases like these, Katherine J. Franz, editor-in-chief of Metallomics, told us. “This time there was a gap between the retraction and the revised version being published, and the revised version is now available,” she said.

Franz added, “My advice to other scientists who may find similar problems is to deal with the issue professionally and honestly so as to uphold the rigor of the scientific process.”

Like Retraction Watch? You can make a tax-deductible contribution to support our work, follow us on X or Bluesky, like us on Facebook, follow us on LinkedIn, add us to your RSS reader, or subscribe to our daily digest. If you find a retraction that’s not in our database, you can let us know here. For comments or feedback, email us at [email protected].

Thank you for sharing stories about scientists who handle errors correctly. It’s good to see examples of science done right.

Indeed

It’s encouraging to see “good” retractions like this one! Kudos to the scientists who acknowledged and handled inadvertent mistakes!