Rolf Marschalek was on vacation when he saw a new paper had been published in the journal Autoimmunity. Marschalek, a biochemist at Goethe University Frankfurt in Germany, was “very upset,” he told Retraction Watch – because he’d peer-reviewed the manuscript and had recommended against publication.

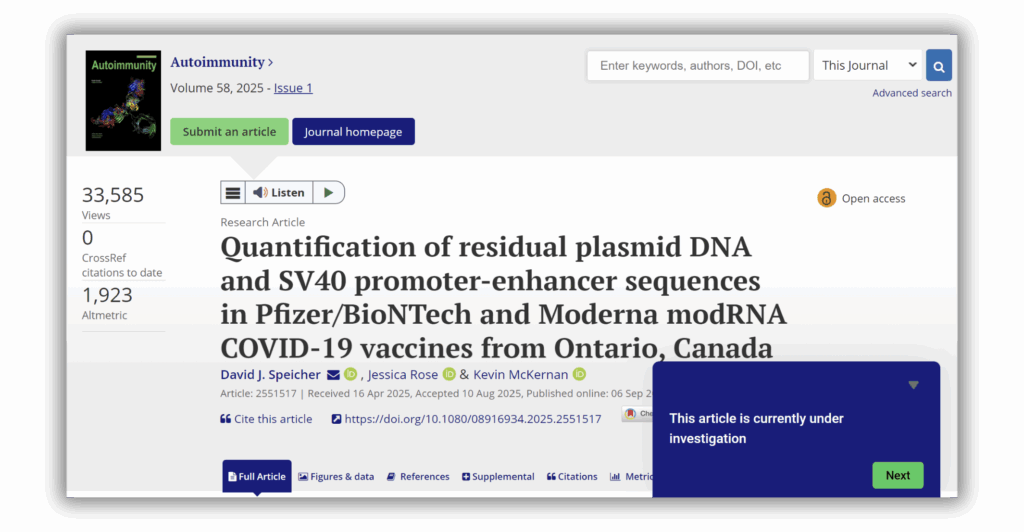

The authors of the paper claimed to find DNA in mRNA-based COVID-19 vaccines above regulators’ suggested amounts. The article appeared online September 6, and within weeks the publisher began an investigation into concerns about its content, as we reported previously.

In Marschalek’s initial review, which he provided to us, he detailed how Qubit fluorometry, one of the methods the authors used to measure the amount of DNA in the vaccine vials, was “not suited” for use when samples contain much higher amounts of RNA than DNA, as is the case with mRNA-based COVID-19 vaccines. He cited a paper he and colleagues had written about methods of quantifying amounts of RNA and DNA in mRNA vaccine vials, including Qubit.

The authors reported using the RNase A enzyme to break down RNA before measuring the amount of DNA, they wrote in the paper. According to Marschalek, the treatment time was too short to fully eliminate RNA in the samples.

He also singled out Figure 2 in the paper, which depicts the amount of DNA in a vaccine lot alongside the number of adverse events reported for each lot. The figure “clearly tells the reader that there is no correlation” between side effects and DNA content, Marschalek wrote in the review.

The authors — David J. Speicher of the University of Guelph in Ontario, Canada; independent researcher Jessica Rose, and Kevin McKernan of the Beverly, Mass.-based company Medicinal Genomics — submitted a revision, which Marschalek reviewed in July. “They didn’t change all the things I recommended,” he told us, and he wasn’t satisfied with the revisions.

“Thus, the revised version of the authors have strengthened my opinion that the whole paper is ‘a mission’ for the ‘anti-vaxx community’ and not a scientific paper,” he wrote in his review of the revision. He again recommended against publication.

Only one other time in his career has Marschalek recommended rejecting a paper and seen it published, he said.

He complained to the editor of Autoimmunity, who told him he could submit a letter to the editor, he said. He did so, but it was not published, because the journal does not publish letters to the editor, a representative of Taylor & Francis, which publishes the journal, told him. However, the publisher began an investigation of the article soon after. Scientific sleuth Kevin Patrick had also contacted the publisher with critiques of the article he had posted on PubPeer.

In his letter, Marschalek summarized the critiques in his reviews and concluded:

If the scientific community does not collectively act to counter such pseudoscientific narratives, the proliferation of misinformation threatens to erode public trust and compromise the integrity of biomedical research.

Paolo Casali, editor in chief of Autoimmunity, confirmed Marschalek did review the paper. But initially he said he was “confused” by our request for comment on the decision to publish the paper. Marschalek “did not recommend rejection of the paper,” Casali said.

According to the associate editor who handled the manuscript, Casali said, Marschalek recommended “major revision,” which the authors performed. The revised manuscript and authors’ letter “were deemed by the AE to have properly addressed the issues” raised by the original reviews, Casali said.

A representative of Taylor & Francis later got in touch with us and offered to provide a statement about “the current situation.” The statement provided on November 24 did not address our question about the review process. Because a “thorough investigation” including “additional independent expert assessment and review of associated editorial processes” is ongoing, “we cannot comment further about the article at this stage,” it said.

Rose, one of the authors of the paper, declined to discuss with us the methodological critiques in Marschalek’s reviews or letter to the editor. But she did question how we obtained the peer reviews, which she called “confidential documents.”

She later posted on Substack that our obtaining the reviews would be “a serious ethical breach.”

Many journals now publish peer reviews online with articles, a practice which falls under the umbrella of “open peer review.”

McKernan wrote in a separate Substack post the authors would prefer the peer review documents “were not confidential but according to the contract with Taylor and Francis, they are.” He also disputed Marschalek’s statement that the RNase A treatment wasn’t enough to get rid of all the RNA in the vaccine samples.

McKernan acknowledged some of the vaccine lots with the most DNA did not have the most adverse events reported, but wrote, “nothing can be inferred from this as we don’t know the lot sizes,” which he said could vary by orders of magnitude.

As we reported in September, McKernan was also an author on a preprint about “synthetic mRNA vaccines and transcriptomic dysregulation” that was withdrawn following critiques from sleuths Elisabeth Bik and Reese Richardson. The manuscript now appears as an “article in press” at the World Journal of Experimental Medicine. According to a PDF of the paper, the peer reviewer’s report gave it a grade of C for quality and a grade of D for novelty, creativity and scientific significance.

Update, Nov. 24, 2025, 8:15 p.m. UTC: This story has been updated to include a statement from Taylor & Francis.

Like Retraction Watch? You can make a tax-deductible contribution to support our work, follow us on X or Bluesky, like us on Facebook, follow us on LinkedIn, add us to your RSS reader, or subscribe to our daily digest. If you find a retraction that’s not in our database, you can let us know here. For comments or feedback, email us at [email protected].

“[Jessica Rose] posted on Substack that our obtaining the reviews would be “a serious ethical breach.” “

Typically peer reviews are the intellectual property of the reviewer, i.e., the person who wrote the review. The draft manuscript is likewise the intellectual property of the authors. So it’s completely ethical for the reviewer to release their review, but it would not be ethical to divulge the manuscript under review. A disconnect, but usually the final isn’t all that different from the reviewed draft.

So calling BS on this argument.

It’s not the case of “intellectual property”. For a journal with anonymous peer review, any disclosure of the review content is a serious ethical breach.

Any disclosure, _except_ by the author of the review, who is always free at any point to break their anonymity.

It seems to me that _after_ a paper is published, anonymous peer review reports may be publicly shared by the peer reviewer (PR). However, this discussion makes me wonder whether some journals might have specific language in their contracts with its PRs that forbids them from disclosing these reports even after a paper is published.

In approximately 40 years of doing peer reviews, I have never been asked to sign a contract. There is always some text associated with the review request saying that one must not share the unpublished manuscript, but I have never seen anything about not sharing the review. (Disclaimer: I’m not in the reviewer pool for the most prestigious journals in my field.)

Journal editors are desperate for peer reviewers. It’s hard to see why they would impose such a condition, as it would likely reduce their peer review pool still more–unless they were going to make a habit of ignoring reviewer comments. I have no proof but I suspect that journals which plan to make a habit of that keep their “peer reviews” in-house or assigned to cronies, and that that’s probably a step en route to not doing them at all. Peer review is a PITA for journals.

Indeed, Mary, I should have written ‘instructions to peer reviewers’ instead of ‘contracts with its PRs. But, I now wonder whether PRs’ violation of some key aspect of those instructions represents a contract violation in the legal sense.

Yes, the article begs for that detail.

Retraction Watch did you ever “ask for the retraction of articles aligned with the established narrative, starting with the randomized trial study of the Pfizer/BioNTech vaccine [9], that was prematurely halted after about six months, offering placebo recipients the chance to vaccinate, thus losing any opportunity to study medium- to long-term effects, especially relevant to carcinogenesis?” https://substack.com/@panagispolykretis/p-179686476

Retraction Watch does not ask for the retraction of articles. That’s not its job: it’s a journalism organization.

They have, however, *covered* retraction of articles aligned with the established narrative: a striking example is the Surgisphere study of hydroxychloroquine for COVID-19, which aligned with general thinking about the uselessness of this medication for COVID, but was retracted due to probable falsification of its data.

In the specific example you give, what would be grounds for retraction? “I wish they had gathered more data” is a critique that can be applied to *any* study, and even if fully correct, does not justify retraction as long as the conclusions reached in the study are appropriate to the data collected.

Can you explain why one should retract a paper published *before* they unblinded the trial and offered placebo recipients to be vaccinated?

It’s remarkable how quickly the pseudoscience/anti-vaxx community resort to inane, wildly exaggerated claims about “slander” and “defamation” when they’re criticized. Those two substacks are among the most moronic screeds I’ve seen from people with advanced degrees.