Annotated images: PubPeer

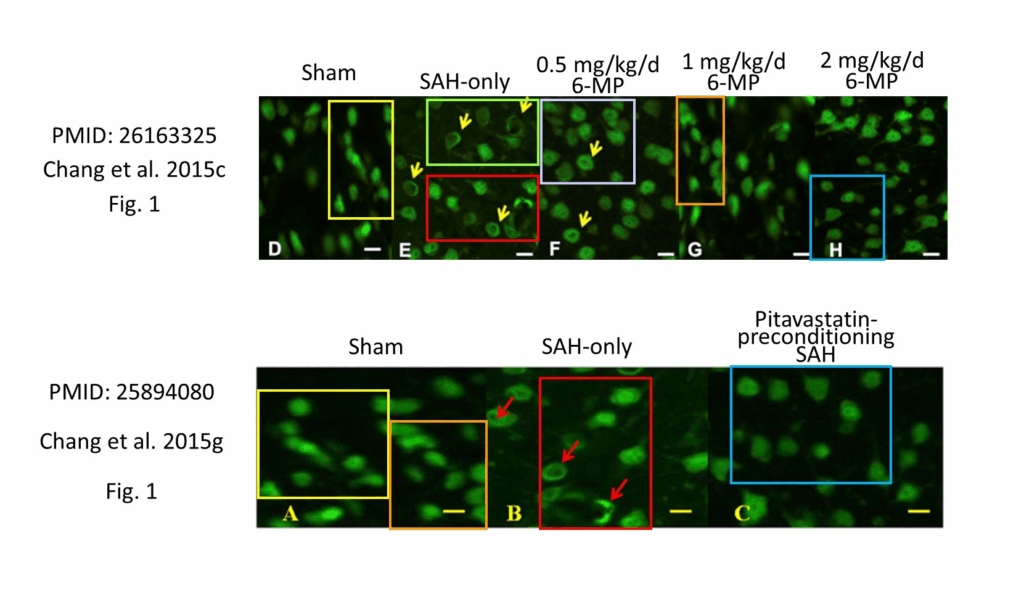

More than 200 papers on ways to prevent brain injury after a stroke contain problematic images, according to an analysis published today in PLOS Biology. Researchers found dozens of duplicated Western blots and reused images of tissues and cells purportedly showing different experimental conditions — both within a single paper and across separate publications.

As we reported last year, René Aquarius and Kim Wever, of the Radboud University Medical Center in the Netherlands, first noticed these patterns in 2023 when they started working on a systematic review of animal studies in the field. They had wanted to identify promising interventions for preventing early brain injury following hemorrhagic stroke. Instead, their efforts turned into an audit of suspicious papers in their field.

Of the 608 studies they analyzed, more than 240, or 40 percent, contained problematic images. So far, 19 of those articles have been retracted and 55 corrected, mostly from the researchers’ efforts to alert journals and publishers about the issues. Almost 90 percent of the problematic papers had a corresponding author based in China, and many appeared in major journals such as Stroke, Brain Research and Molecular Neurobiology.

When Aquarius and Wever first saw how many animal studies existed on early brain injury, they were encouraged, and thought “it’s great that there’s so much evidence,” Wever recalls. But they noticed nearly every intervention had only been tested once, which was unusual since promising results usually lead to follow-up studies. When they looked at the studies more closely, “strange” patterns emerged among the images, Aquarius said, including manipulated protein bands and images of brain tissue reused in other papers. The problems were so pervasive they abandoned their review and instead began investigating how widespread image duplication was in their field.

At first, the pair tried to check the images manually, but the work was too slow. So they turned to ImageTwin, which cross-checks uploaded images against a database, making the process “more efficient and accurate,” Wever said.

The results showed a sprawling network of images that not only appeared in articles on early brain injury, but also showed up labeled under different experiment conditions across studies on Alzheimer’s disease, epilepsy and lung cancer, and other unrelated fields. Among those papers, a Chinese investigation found one had plagiarized pictures, another paper didn’t have the ethics approval for the experiments, and another where authors blamed outsourcing for the issues. In one case, authors described an image as vessels in a human brain, but the same image also appears in an animal study. It was “like an oil spill,” said Wever.

In total, their analysis found 37 of these papers in research fields other than early brain injury. Overall, 133 of the 608 articles contained an image that also appeared in another publication, a pattern typical of paper mills or image reuse among an author group, Aquarius said.

Paper mills might be behind the rapid increase in published articles after 2014, because they can publish several hundred studies in the time it takes to do one legitimate study, the researchers said. In 2013, there were only 18 papers on the preclinical interventions published, compared with 64 in 2017. Paper mills aren’t uncommon in the field; as we reported last year, an Indian paper mill iTrilon was linked to several papers published in Life Neuroscience.

Aquarius and Wever’s findings have already led to an institutional review on the work of a stroke researcher. As reported in The Transmitter, Loma Linda University is reviewing the work of John H. Zhang after Aquarius and Wever found possibly duplicated Western blots and microscopy images in nearly 100 of his papers, which were published in 38 journals over two decades.

In their new publication, the researchers took a conservative approach to identifying image reuse, so Aquarius called the 40 percent estimate a “best-case scenario.” Many of the papers might also contain other problems, he added, such as questionable citations or tortured phrases.

Occasionally, Aquarius and Wever changed their mind about a problematic paper. In one case, an author contested Aquarius’ comment on PubPeer about duplicated parts of an image because the figure had been altered by the publisher and not the author. In older papers, editors sometimes replaced labels on figures by cutting and pasting parts of the image — a now uncommon practice known as corner cloning. “Back then it was considered no big deal,” Aquarius said.

Almost 90 percent of the problematic papers Aquarius and Wever identified had corresponding authors affiliated with Chinese institutes. One reason could be a country-wide initiative that pressures researchers to publish to improve a university’s ranking, Aquarius and Wever said in their analysis. Cash-based incentives to publish were also only banned in 2020. Other analyses have identified similarly widespread issues among Chinese institutions. One found retractions in neurology were most common among authors affiliated to Chinese institutions, and more than half of residents across 17 hospitals in southwest China said they had committed research misconduct, according to a survey.

The largest share of problematic papers appeared in journals published by Elsevier, which accounted for 65 of those flagged, followed by Springer Nature with 44. The single journal containing the most problematic studies was Molecular Neurobiology, a Springer Nature title, containing 13 flagged out of the 23 the journal published on the topic. Brain Research, an Elsevier publication, and Stroke, a Lippincott Williams & Wilkins publication, followed with 10 papers flagged each.

An Elsevier spokesperson told us journals do use tools to check images against datasets, and “the investigation is still ongoing regarding these particular papers,” they said.

Tim Kersjes, head of research integrity, resolutions, at Springer Nature, told us, “We are aware of concerns with a number of these papers and have already been investigating the matter carefully, following an established process and in line with COPE best practice,” he said. “For journals where we identify a number of problematic papers, we work with the editors to ensure that they have access to appropriate training and resources so that issues do not recur going forward.”

The journals have varied widely in how they handled the flagged papers, the researchers said. Some acted quickly to issue corrections or retractions, while others were slow to respond or didn’t reply at all. The researchers singled out Stroke, one of the field’s most prominent journals, as sporadic in engaging with the problematic papers. “It was very, very difficult to get any contact with them,” Aquarius said.

A media representative of the American Heart Association, which publishes Stroke, said “The editors and staff balance the need for timely responses with the need for thorough, detailed work following COPE guidelines.” She said their journals have dedicated editors who use image assessment tools to check images before publication, but “no system will be perfect.” Stroke has issued expressions of concern for the articles linked to the Loma Linda review, and is awaiting the results.

In some cases, journals made stealth corrections by replacing figures without issuing any formal notice of the change. The lack of consistency between papers and publishers was frustrating, Wever said. Among three articles using the same image, one could be retracted, one corrected, and one left untouched, she said. “There were so many discrepancies that were not really helpful.”

Even after journals issued corrections, problems still persisted. Out of the 55 corrections, one in six still contained image issues. This could happen when editors accept replacement images from authors without verifying them, Aquarius speculated. Or they were detected after ImageTwin added more images to its database. Rather than pointing fingers, Aquarius said the important thing is “the scientific record is still not correct.”

Aquarius and Wever say their role is to document the issues that they see, but not to decide what happens next. “[We] both have our opinions on what should happen with these papers, but we are not the ones that are going to do it,” Aquarius said. “It’s up to the authors, institutes, journals and funding agencies to make some decisions.”

Update, Oct. 30, 2025: This story was updated to add comment from Springer Nature.

Like Retraction Watch? You can make a tax-deductible contribution to support our work, follow us on X or Bluesky, like us on Facebook, follow us on LinkedIn, add us to your RSS reader, or subscribe to our daily digest. If you find a retraction that’s not in our database, you can let us know here. For comments or feedback, email us at [email protected].

The pressure of increasing the university ranking or shouldn’t be the “reason” or “excuse” of any academic misconduct.

“Tim Kersjes, head of research integrity, resolutions, at Springer Nature, told us, “We are aware of concerns with a number of these papers and have already been investigating the matter carefully, following an established process and in line with COPE best practice,” he said. “For journals where we identify a number of problematic papers, we work with the editors to ensure that they have access to appropriate training and resources so that issues do not recur going forward.””

What about clearing the backlog? Anybody can kick it into the long grass, but what about clearing the publications with problematic data that Springer Nature has already published? That’s something Springer Nature could do “going forward”.

Fraud in bioscience is the moral equivalent of arson. It may or may not lead to deaths.