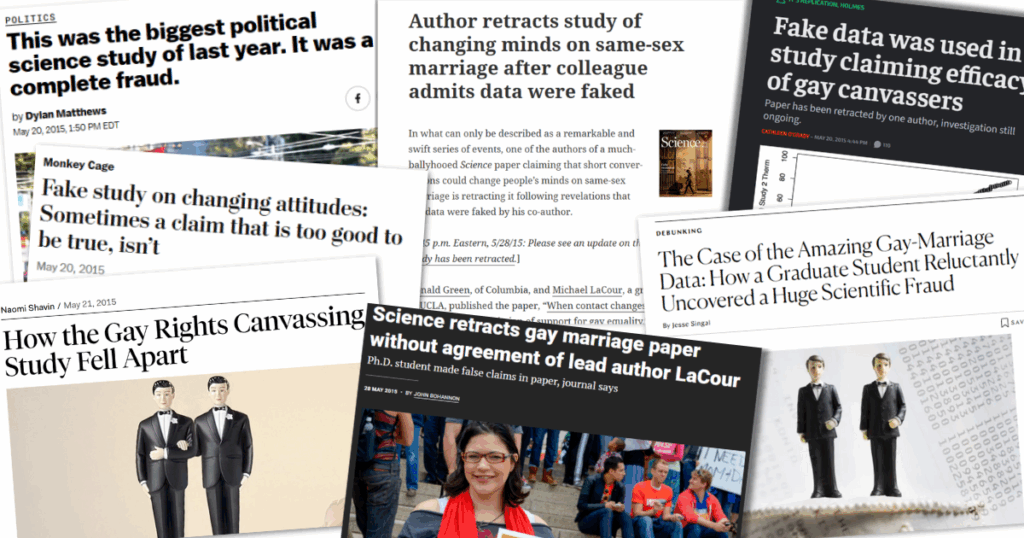

“Gay Advocates Can Shift Same-Sex Marriage Views,” read the New York Times headline. “Doorstep visits change attitudes on gay marriage,” declared the Los Angeles Times. “Cure Homophobia With This One Weird Trick!” Slate spouted.

Driving those headlines was a December 2014 study in Science, by Michael J. LaCour, then a Ph.D. student at the University of California, Los Angeles, and Donald Green, a professor at Columbia University.

Researchers praised the “buzzy new study,” as Slate called it at the time, for its robust effects and impressive results. The key finding: A brief conversation with a gay door-to-door canvasser could change the mind of someone opposed to same-sex marriage.

By the time the study was published, David Broockman, then a graduate student at the University of California, Berkeley, had already seen LaCour’s results and was keen to pursue his own version of it. He and fellow graduate student Joshua Kalla had collaborated before and wanted to look more closely at the impact canvassing could have on elections. But as the pair deconstructed LaCour’s study to figure out how to replicate it, they hit several curious stumbling blocks. And when they got a hold of LaCour’s dataset, or replication package, they quickly realized the results weren’t adding up.

The two graduate students found themselves in somewhat uncharted territory for how to share their critique. They wrote up their findings, recruiting help from Yale statistician P. Aronow. They shared the report with Green, the senior author on the paper, who confronted LaCour with the critique.

Then, the trio posted the report with its unassuming title, “Irregularities in LaCour,” online.

It was “like our personal Cuban Missile Crisis,” Broockman said in an interview with Retraction Watch last month. “There was basically this period between when our little PDF report went online and our little world exploded.”

Their revelations about “statistical irregularities” and false statements triggered the paper’s downward spiral, cataloged in nearly real time on Retraction Watch and widely reported elsewhere, culminating in the paper’s official retraction 10 years ago this week.

A decade later, Broockman, Kalla and Green continue to study persuasion in politics, among other topics. Their involvement in one of the most widely publicized retractions had some lasting effects on how they approach research. And the intervening years have also brought some welcome changes to research and data practices in their field.

‘There’s no rule book for this’

After Broockman and Kalla’s report went public, their peers were unsure how to react. “A lot of the fears we had felt like they were starting to come true,” said Broockman, now an associate professor at Berkeley. “People were like, ‘is this the right thing to do? Was this the right procedure?’” he said. “We were like, ‘there’s no rule book for this.’”

The same is true today. Post-publication peer review has gained more prominence since 2014, thanks to data sleuths, PubPeer and other efforts to police the literature. This week, a team of sleuths published a series of 25 guides on how to spot integrity issues. But a post on PubPeer is unlikely to draw attention beyond certain circles, and formal investigations trigger processes that move at an academic pace.

“I think there’s still a cultural problem in academia — and there was at the time — there’s just a lot of costs associated with criticizing existing research,” Broockman said. “The stories that you’re worried people are going to tell about you, I think that remains a big deterrent for people to come forward with whatever issues they have. I think academia has made a little bit of progress on that and could make more.”

When Broockman and Kalla spoke with us, news had just broken that MIT called for the withdrawal of an AI study done by an economics graduate student. Kalla hadn’t been familiar with the research — which had not yet been published but was posted as a preprint — or the university’s announcement. But he had read Stuart Buck’s May 18 newsletter recounting his critique of the study — and the backlash Buck faced for asking questions about it.

“He got pushback for not following proper etiquette, for not being kind and understanding and kind of wrong to be questioning the research paper,” said Kalla, now an associate professor at Yale University. “I don’t know if the norms have changed over the last 10 years, but Stuart is raising some of those same concerns that we had 10 years ago.”

Sometimes, no matter which option a person chooses, there’s pushback, Broockman said.

“I think it’s a problem that so many people’s first instinct in these circumstances is to criticize the person raising the issue,” he said. “That’s really problematic. I think Stuart’s post shows that this remains a problem.”

Kalla said he encourages early-career researchers to take a direct, respectful approach when critiquing anyone’s work. “The key advice I give to graduate students is to have that kind of respect and curiosity, since oftentimes there aren’t the smoking guns that David and I had 10 years ago,” he said.

‘The hero here is open data’

In 2014, publishing datasets, code and documentation with research papers was relatively uncommon. But that’s ultimately what led Broockman and Kalla to realize the “irregularities” they had found with LaCour’s study execution were something more.

“The hero here is open data. That’s what led us to do this,” Broockman said. “This is one example – it’s an extreme example – of why open data is important.”

“Ten years ago, the idea of pre-analysis plans, the idea of open data, the idea that you need to have reasonable sample sizes and studies, that was much more like a fringe, vanguard thing,” Broockman said. “My sense is that in the three main social science quantitative fields of psychology, political science and economics, I think we won that war. I think that’s pretty universal now.”

Kalla was somewhat less certain. “I’m not sure if I would say the war is totally over. I think there’s definitely still lots of pushback, especially around both pre-analysis plans and statistical power,” he said. “There’s a perception that our job is to publish and to keep our jobs, and not necessarily to do the best research possible. And sometimes these scientific best practices come at odds with those competing goals.”

Kalla and Broockman are meticulous researchers by nature, but their involvement in the Science retraction amplified that trait. “I think given the prominence of this retraction, I always feared people are going to double check my work,” Kalla said. “So I think that that made me always be careful, to try extra hard to make sure everything is buttoned down, everything is double and triple checked.”

Green acknowledged he didn’t do his due diligence as a coauthor, telling us at the time:

Convinced that the results were robust, I helped Michael LaCour write up the findings, especially the parts that had to do with the statistical interpretation of the experimental design. Given that I did not have IRB approval for the study from my home institution, I took care not to analyze any primary data — the datafiles that I analyzed were the same replication datasets that Michael LaCour posted to his website. Looking back, the failure to verify the original Qualtrics data was a serious mistake.

The study and its fallout prompted him to make changes in his collaborations. “My data-related collaborations now involve teams of people (rather than single individuals) working on data collection and data analysis,” Green said last month by email. “Research materials are shared and date-stamped. Replication materials work from basic inputs to final outputs.” And, he added, he no longer supervises doctoral students from other schools.

Trust but verify

A year after the LaCour retraction, Broockman and Kalla published a study finding that 10-minute, in-person conversations between door-to-door canvassers and voters in South Florida could “substantially reduce transphobia” and that the gender identity of the canvasser didn’t matter. (The irony of the finding’s similarity to LaCour’s, and its publication in Science, wasn’t lost on the media either.)

Since then, they’ve conducted “at least nine or 10 replications in various forms related to different issues,” from work on transphobia to immigration rights, Kalla said. “This style of non judgmentally exchanging narratives through door-to-door canvassing can durably reduce people’s prejudicial views towards these various out groups.”

Most recently, they posted a preprint of a study on how endorsements and special interest groups affect voter behavior in primaries and general elections. By surveying 31,000 respondents during 2024 elections in 27 congressional districts, they found “primary voters actually struggle to identify which candidates match their views. So they rely on other cues—especially from interest groups who might help drive polarization,” Broockman posted on Bluesky.

Just as they’ve stayed on theme with their research, so too have their opinions on the infrastructure for research. Shortly after the LaCour retraction, Broockman and Kalla wrote an editorial in Vox reacting to coverage citing “a growing number” of retractions. They cautioned retractions were a sign that the system is strong, not weak. They wrote at the time:

The fact that we are especially likely to see and hear about the errors scientists make does not suggest scientists are especially prone to making mistakes. Rather, it shows that scientific errors are increasingly likely to be detected and corrected instead of being swept under the rug.

Has that view changed? “When scandals like this MIT thing this week come out, those should make people more confident in academic research, because they show there is an ecosystem to catch this stuff,” Broockman said in our recent interview. “I think we should be wary of proposals to over-regulate academic research, to solve for these rare events.”

He continued: “But if we’re going to not over-regulate the doing of the research, that means we need the fire alarm — and that’s what you guys [Retraction Watch] are — and we need the researchers doing the research knowing that there’s a reasonable chance they will get caught.”

He likened blatant fraud cases like LaCour’s to “the airplane crashes of academic research” — they get a lot of attention, but in terms of what affects more people, “they attract far disproportionate attention,” he said. “If I were making a top five list of ways academia is not producing research that is as truthful as it could be, I don’t think fraud would be in my top five.” Issues like p-hacking, selectively including data, and deviating from research plans are all smaller infractions that are bigger issues, he said.

Carelessness has a large effect in the literature, too. “For me, the biggest takeaway is, sure, fraud happens,” Kalla said. “I think the bigger concern in research is sloppiness.” He and Broockman are systematic in their collaborations, carefully checking each other’s code and work. “And I think that extends to collaborations with other people as well. The trust-but-verify mentality,” Kalla said, “and definitely not in a skeptical, hostile, fraud based way. It’s very easy to make mistakes.”

Green also continues to study U.S. public opinion and political behavior, branching out to study the influence of mass media in low- and middle-income countries. “Several of my field experiments since then have focused on how narrative entertainment shapes beliefs, attitudes, and behavioral intentions,” he said. Those include studies on how a Tanzanian radio drama influenced attitudes on early and forced marriage, and the influence of a media campaign on violence against women in Uganda.

Coda

Ten years on, Green, Broockman and Kalla say the study and its demise still come up periodically, but far less often than it did in the year or two immediately after.

“My sense is that this episode is discussed fairly widely when scholars and instructors assess the replication crisis in social science, in part because the case illustrates both why research might fail to replicate (in this instance, due to fraud) as well as the norms and institutions that have emerged to expose replication failures (such as the availability of replication data that in this case exposed how fabricated data were grafted onto an existing dataset),” Green said.

He talks about it indirectly in his undergraduate textbook, but “students seem to be less and less familiar with the episode as time passes,” he said. “I suppose that a senior now would have been in elementary school when it happened.”

Every once in a while a student will ask Kalla about the case, he said, and Broockman said it mostly comes up when he’s talking to researchers in other disciplines, but not so much anymore.

For Broockman, the story has an added personal note: Eight years ago, it came up on a first date — with the man he’s now engaged to. “He had listened to the ‘This American Life’ episode about all of this,” he said. “So maybe that served me well.”

Like Retraction Watch? You can make a tax-deductible contribution to support our work, follow us on X or Bluesky, like us on Facebook, follow us on LinkedIn, add us to your RSS reader, or subscribe to our daily digest. If you find a retraction that’s not in our database, you can let us know here. For comments or feedback, email us at [email protected].

“Kalla said he encourages early-career researchers to take a direct, respectful approach when critiquing anyone’s work. ‘The key advice I give to graduate students is to have that kind of respect and curiosity, since oftentimes there aren’t the smoking guns that David and I had 10 years ago,’ he said.”

I agree and something similar is also what I recommend to my students. And even though this is Retraction Watch, I am generally against retractions. Sure, some things must be retracted, but honest mistakes and scientific debates should never yield retractions.

Yet, with respect to my earlier comment regarding PubPeer (see https://retractionwatch.com/2025/06/04/cosig-sleuths-publish-toolkit-post-publication-review), there are many things in current publishing that do not really mandate any meaningful engagement with anyone — publishers notwithstanding. As has been argued recently (https://www.science.org/content/blog-post/cleaning-scientific-reports-can-it-be-done), a word “deletion” should be perhaps used in some cases instead of a word “retraction”. These cases, many of which are documented in PubPeer, involve blatant tortured phrases, blatant plagiarism, blatant citation manipulation, blatant nonsense, including AI-generated nonsense, and other blatant cases of obvious fraud.

Otherwise, I applaud the movement toward open data and more generally open science. With this movement, including pre-prints, eventually we might not even need “prestige”, retractions, and other related things because we wouldn’t need gatekeepers to begin with. Everyone would be judging what he or she reads by himself or herself, as it should be. And academia would be a healthier place.