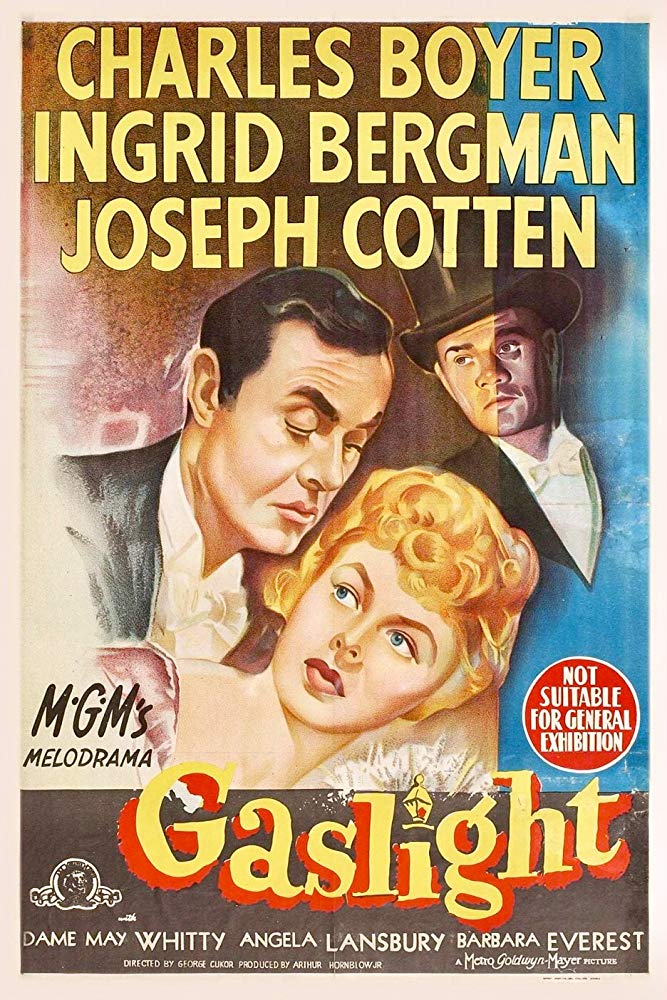

We’ve covered a number of stories about scientific whistleblowers here at Retraction Watch, so readers will likely be familiar with what often happens to them: Their motives are questioned, they are ostracized or pushed out of labs, or even accused of misconduct themselves. But there’s more to it, says Kathy Ahern in a recent paper in the Journal of Perinatal and Neonatal Nursing. Ahern writes that “although whistle-blowers suffer reprisals, they are traumatized by the emotional manipulation many employers routinely use to discredit and punish employees who report misconduct.” Another way to put it is that “whistleblower gaslighting” — evoking the 1944 film of the same name — “creates a situation where the whistle-blower doubts her perceptions, competence, and mental state.” We asked Ahern some questions about the phenomenon.

We’ve covered a number of stories about scientific whistleblowers here at Retraction Watch, so readers will likely be familiar with what often happens to them: Their motives are questioned, they are ostracized or pushed out of labs, or even accused of misconduct themselves. But there’s more to it, says Kathy Ahern in a recent paper in the Journal of Perinatal and Neonatal Nursing. Ahern writes that “although whistle-blowers suffer reprisals, they are traumatized by the emotional manipulation many employers routinely use to discredit and punish employees who report misconduct.” Another way to put it is that “whistleblower gaslighting” — evoking the 1944 film of the same name — “creates a situation where the whistle-blower doubts her perceptions, competence, and mental state.” We asked Ahern some questions about the phenomenon.

How is gaslighting typically used against whistleblowers? What are some examples of what perpetrators (including institutions) do?

Whistleblower gaslighting entails officers of an institution using their authority to deceive a whistleblower so that he stays engaged in a process designed to harm him. Employees have an expectation of support derived from social norms regarding workplace interactions and formal policies. Whistleblower reprisals have a sting of betrayal that is largely imperceptible to outsiders because gaslighting institutions use deception to exploit the employee’s trust in his employing institutions.

The whistleblower obviously trusted his employing institution enough to report his concerns about misconduct in the first place. One gaslighting strategy is to use this trust to force the whistleblower to repeatedly defend himself against bogus disciplinary charges presented as genuine complaints. Eric Westervelt describes whistleblowers at the U.S. VA who were subjected to investigations of unspecified charges such as “creating a hostile work environment” or “abuse of authority”, although subsequent FOI requests yielded no details of the charges. As a gaslighting strategy, the dual purpose of false charges is to both discredit and exhaust the whistleblower.

One aim of institutional betrayal is to create feelings of hurt and resentment that will drive a wedge between the employee and any potential sources of support. In an Australian university, an entire office was given an extra week of holidays except for one researcher who was barred from the extra leave and found out only when she turned up to work on her own. Another Australian university searched an academic’s emails to find examples of “disrespectful comments” about colleagues which were used as justification for misconduct proceedings.

A major tell of whistleblower gaslighting is how multiple departments collude to create pressure in as many ways as possible through ostensibly legitimate means. Westervelt describes denials of reasonable requests for sick leave arrangements and remote access to essential information. In other examples, the union took a vote of “no confidence” in a whistleblower, and a whistleblower describes how his employment records were falsified so his eligibility for benefits was adversely affected.

Petty nastiness is a feature of gaslighting because it can be plausibly explained away as an insignificant act when in fact it is deeply hurtful. Westervelt describes how a supervisor took away a whistleblower’s office keys, army service medals and an American flag in a case that she got for 20 years of honorable military service. “It’s a kind of psychological violence,” [the whistleblower] says, tearing up over the loss of her Army service mementos. “I feel violated. I feel like someone robbed me.”

Petty, spiteful acts are an important component in whistleblower gaslighting because the general public’s assumption is that it is patently implausible for an elite institution to indulge in middle school “mean girl” antics. The multiple minor social aggressions can be explained away, so when a target eventually reacts to repeated provocation, the “mentally unstable” depiction of a whistleblower is reinforced.

How can gaslighting affect whistleblowers?

Descriptions of whistleblower experiences and outcomes in the literature show a constellation of symptoms that are very similar to complex post-traumatic stress disorder (C-PTSD) typically found in survivors of child abuse. It is hypothesized that the abuse by a trusted, more powerful adult leads to a general distrust of self and others. Adults with C-PTSD have trouble regulating intense negative emotions, and feel disconnected to other people.

The common narrative of whistleblowers is that at first they believe the repeated reassurances of kindly institutional officers. However, over months or years, the whistleblowers find that inevitably their expectations of due process are betrayed by an inexplicable incompetence at every turn. The whistleblower becomes anxious, despairing and mistrustful – symptoms that mirror paranoia. However, these symptoms are not the result of delusions, but are a normal response to repeated promises and betrayals.

The other symptom I see in targets of whistleblower gaslighting is a desperate urgency to be believed. This looks a lot like an “obsession,” but as with the “paranoia,” it is not the result of a mental disorder. It is more like the normal response of someone who spent 10 years in jail for crime he didn’t commit. Such a person is indefatigable in pursuit of having his name cleared, as are targets of whistleblower gaslighting who also are intent upon clearing their names and reputations.

The final constellation of symptoms parallels those of romantic gaslighting targets who describe how the manipulations they endured eroded their ability to make judgements. They ended up feeling overly sensitive and mentally unstable as a result of the manipulations of their gaslighting partner.

This constellation of whistleblower outcomes is amply described in the whistleblower literature and forms a surprisingly consistent pattern of:

- Diminished self-worth.

- Intense, overwhelming negative emotions such as despair, fear and frustration

- Disconnection from people.

- Constantly seeking validation of the experience of injustice.

- Distrust of self and others, often mimicking paranoia.

- A desperate urgency to be believed, akin to obsession.

- An eroded ability to make judgements.

- Feeling overly sensitive and mentally unstable.

In my view, if these symptoms occur within a context of having reported misconduct that culminated in a dual conclusion of “no evidence of the alleged misconduct” and “unstable, underperforming employee”, these are definitive of whistleblower gaslighting. Of course, empirical research is required to test this.

You provide some “red flags” to alert researchers to the occurrence of gaslighting against whistleblowers. Can you share some of the most notable/common ones?

The literature describes a pattern of behavior, a choreography enacted by many officers within an institution. Wherever the whistleblower turns, they are met with the two-step of reassurance that their concerns are taken seriously and inexplicable incompetence in investigating allegations of reprisals. Every request in the gaslighting choreography seems to end with polite version of, “not my job, go somewhere else.” The whistleblower is in a constant state of hope that this officer will do their job followed by confusion at this person’s inability to do their job properly. Meanwhile, overt denigration and spurious complaints about the whistleblower are zealously pursued.

Other common red flags include:

- Reprimands and complaints only start after the alleged misconduct was reported.

- Proactive steps to prevent reprisals are not undertaken.

- The institution downgrades allegations of reprisals to a grievance procedure, which does not enable wrongs to be redressed.

- The response is inadequate and includes willful blindness to evidence, and stonewalling.

- The whistleblower’s experiences are denied, such as unfair treatment being called a “personality clash” or “miscommunication”.

- Supervisors, HR, union reps and/or senior executives fail to intervene in retaliatory actions.

Many people fear repercussions for speaking up. But do you think there is enough awareness of the role gaslighting can play?

No. Whistleblower gaslighting depends upon the arguably naïve trust by whistleblowers and the general public that allegations of misconduct will be addressed by the institution with due diligence according to policy, procedures and the law. This assumption makes it easier to accept the narrative of a good institution and a vexatious employee over a bizarre narrative of a cruel, Machiavellian institution.

When whistleblowers disclose that they reported misconduct and ended up losing their jobs, they frequently get a rhetorical, “well what did you expect”? They expected what most people would expect: an honest investigation that would reveal the facts.

What prompted you raise awareness of this issue?

The Gustavo German report by Retraction Watch in Science elicited dozens of polarized comments. Many commenters felt that Harvard University would never treat a doctoral student so egregiously for reporting concerns about research misconduct. Many others strongly believed that a Harvard professor accused of misconduct could well manufacture a scenario that ended with a doctoral student being strapped to a stretcher and hauled off for compulsory psychiatric assessment in the middle of the night.

I couldn’t get my head around why some commenters seemed reluctant to even consider the possibility that Gustavo might have been set up. Things finally fell into a coherent theory when I was researching betrayal trauma in adult survivors of childhood abuse. I was reminded that people who had never experienced or witnessed abuse often react with disbelief to survivor accounts.

What do you think the scientific and academic community can do to better protect whistleblowers?

Stop assuming that whistleblower protection legislation works, when in many instances it is just another layer of false reassurance. Queensland has whistleblower protection legislation, but as far as I know, no-one has ever been charged for enacting reprisals on a whistleblower. Frankly, I think that anyone who stumbles across misconduct is best protected by the knowledge that their institution will not necessarily act ethically or within the law.

The presence of signs and symptoms of gaslighting in a whistleblowing context should be accepted as evidence of reprisals. For too long, the negative effects of whistleblower gaslighting have been used to further the myth of an under-performing employee who made up accusations of misconduct because he was disgruntled and keeps harping on about it.

In the long run, whistleblower gaslighting needs to be recognized as an aggravating factor in whistleblower reprisals and reflected in legislation and penalties.

Anything you’d like to add?

If the phenomenon of whistleblower gaslighting were widely acknowledged and its strategies routinely exposed, institutions would find it counterproductive to engage in this deceptive practice because it provides evidence in support of the whistleblower’s account. The more definitively whistleblower gaslighting strategies can be identified, the better for whistleblowers. To this end, the phenomenon of whistleblower gaslighting needs to be empirically studied.

Like Retraction Watch? You can make a tax-deductible contribution to support our growth, follow us on Twitter, like us on Facebook, add us to your RSS reader, sign up for an email every time there’s a new post (look for the “follow” button at the lower right part of your screen), or subscribe to our daily digest. If you find a retraction that’s not in our database, you can let us know here. For comments or feedback, email us at [email protected].

When I was in graduate school, I noticed a significant number of issues in my lab and adjacent work spaces. Inadequate PPE for hazardous chemicals, poor training for complex equipment, food in nominally BSL2 areas, personnel mishandling hazardous materials to name a few.

After repeated informal requests to correct some of these issues, I wrote a rather lengthy formal request to my PI pointing out all of the various issues I had observed over the past month. I was fed up with the lack of safety and poor quality standards. I expected my PI to be a bit defensive. What I did not expect was my PI to tell me that after sharing the letter with a colleague, the colleague recommended that my PI fire me. Now, my PI did not name the colleague who stated this, but this conversation precipitated my eventual exit from my graduate program and return to the workforce.

I’m glad it happened because I realized I was not actually being trained in grad school in a manner that could not be done in industry. Yet, I can’t help but wonder whether my PI actually shared that letter with a colleague. Or if they merely told me that recommendation to push me out.

Although I have no experience in scientific research, in my role as a supervisor, I have seen “unstable, underperforming employee[s]” who complain about all sorts of stuff. Having clear procedures for protecting whistleblowers who officially report misconduct is very important, but removing employees who are poisoning an organization’s culture is also a best practice of top performing organizations. You can do both.

I would challenge that the majority of supervisors in hierarchical institutions really do not understand performance nor how to rate it. W. Edward Deming, management consultant and author mostly associated with quality management, considered performance appraisals a “deadly disease” for organizations wishing to optimize performance outcomes. Performance is a management issue because they control the resources and processes – how resources are used. Read about the Red Bead Experiment. Further, culture comes from the top. When misconduct is reported, it implicates top management in one way or another. Thus, the sanctioned reprisal and abuse of authority.

Why do institutions behave this way? It’s as if the biggest stakeholders at the institutions believe that their continued success depends upon not broadly disrupting the behavior being challenged. In other words, there’s some kind of fundamental misalignment between behaviors that the authorities (rightly or wrongly) believe an institute must pursue/tolerate to be successful, and behaviors that are permissible according to the rules.

Of course I want the bad behavior to stop, but the question does occur to me: regarding “rightly or wrongly” … is it *rightly* believed that institutional success depends on impermissible behavior?

The process of gaslighting the whistleblower is remarkably similar to what happens to a victim of abuse by a professional when they report to a licensing body and/or employer of the violator.

It is oftentimes that the legalized reporting practices end up causing more harm than the original problem. The trust is the medical, therapeutic or religious system can be shattered by the manner which is used to silence the whistleblower.

Good term, terrible example.

“The Gustavo German report by Retraction Watch in Science elicited dozens of polarized comments. Many commenters felt that Harvard University would never treat a doctoral student so egregiously for reporting concerns about research misconduct. Many others strongly believed that a Harvard professor accused of misconduct could well manufacture a scenario that ended with a doctoral student being strapped to a stretcher and hauled off for compulsory psychiatric assessment in the middle of the night.

I couldn’t get my head around why some commenters seemed reluctant to even consider the possibility that Gustavo might have been set up. Things finally fell into a coherent theory when I was researching betrayal trauma in adult survivors of childhood abuse. I was reminded that people who had never experienced or witnessed abuse often react with disbelief to survivor accounts.”

As one of the prior commenters now charged with being reluctant to consider that German was “set-up” I feel that the record should be clarified.

No, I was not reluctant to consider this possibility – indeed as a whistleblower suffering gaslighting myself I was particularly sensitive to the possibility.

The facts don’t bear this out.

German on the basis of a single conversation with another lab member months earlier reported that Rubin may had falsified one panel in a massive paper. This lead to a 7 month investigation by Harvard, confiscation of computers and notebooks and other disruptions – and a stain on an otherwise flawless reputation [Rubin’s] that apparently continues to this very day. Rubin – in fact – had not committed any misconduct.

Harvard did not “gaslight” German – on the contrary – though this totally happens. Instead – after bending to German’s false accusation against Rubin – Harvard bent over backwards to follow the judges instructions as ridiculous as they were and gave German every opportunity to finish his dissertation work [he didn’t] – even going to the absurd measure of banning Rubin from his own lab when German was present.

And, no Rubin did not order a forced mental exam of German – that was the professional judgement of a Harvard phycologist.

Where is the gaslighting in this case?

Cynic got it right in the comments:

“In my book (not in the eye of law of course), the trauma of being accused of research misconduct and having my computer and lab note confiscated (when in fact I did nothing wrong) would be just as traumatizing if not more so than being dragged to hospital for a mental exam (when in fact I am totally not crazy). In the latter case, the misunderstanding could get cleared up in hours.”

Maybe some effort could also be put into coining a term for falsely accusing a researcher of misconduct.

Defamation comes to mind.

I completely identify with this article and have been a target of harassment and bullying, along with the gaslighting. (I have chronicled my story on nopgs.com)

Gang-bullying (mobbing) is an institutional tactic to rid the organizations of whistleblowers. Some have referred to mobbing as psychological terrorism.

First, I would challenge that the majority of supervisors in hierarchical institutions really do not understand performance nor how to rate it. W. Edward Deming, management consultant and author mostly associated with quality management, considered performance appraisals a “deadly disease” for organizations wishing to optimize performance outcomes. Performance is a management issue because they control the resources and processes – how resources are used. Read about the Red Bead Experiment. Further, culture comes from the top. When misconduct is reported, it implicates top management in one way or another. Thus, the sanctioned reprisal and abuse of authority.

Most of these issues of reprisal pivot around the misuse of institutional power. I believe bullying and gang-bullying are themselves corruption because they involve the misuse of agency power and policy. Institutional gaslighting implies mobbing and a

collective action corruption.

I think that we need to get bullying and harassment out of the HR domain and into the health and safety domain. HR uses “performance management” too often as a means of destroying whistleblowers. HR is weaponized in corrupt institutions. Performance is so subjective and misunderstood in most cases. Performance should not be seen as valid unless the processes used to define performance are proven valid. They seldom are.

This is extremely helpful. I was in the first group of intramural fellows at NIAAA in Bethesda in 1983. After 5 years at the institute (2 as staff), I reported what I perceived as altered data by a colleague. Following an investigation, I was notified by the lab director that – instead of the promised tenure – my contract was not being renewed because “nobody likes you” (including my officemate). After not talking to my officemate for a few days, she asked what was up and was crushed when she heard I thought she felt poorly of me. I later found out that I had many supportive friends at work. Years later I was told by colleagues that the reason for my termination was due to my reporting of the possible data fabrication. But not until now did the reason for being told “nobody likes you.” Thank you.

I am experiencing gang bullying and have off and on for 5 years over a workplace incident gone viral. It is cruel and unusual and horrifying. It is not confined to the office but is a personal and professional annihilation. Its bizarre to think the organization pursuing this is so blood thirsty. I kept fighting back and as someone once told me, snitches end up in ditches.

There is a reason why so many people view universities with disgust (especially ones that proclaim their values or DEI BS). These institutions are rotten to the core. One can hope that the largest will be turned around, but many universities will need to die in order for others to take the rot seriously.

When it comes to whistleblowers, one would need to be insane to risk that as a graduate student or faculty without tenure. Put your head down and say nothing until you are safe or somewhere else. Large institutions are by nature corrupt. The last twenty years have seen a dramatic increase in corruption as hiring has become ever more political. It is really a shame how far these institutions have fallen.

Try being a whistleblower as an undergraduate, after being mobbed and warning in feedback about an imminent suicide of a student due to a toxic culture, and then, mere months later, a student dies by suicide due to bullying and the story is all over the press.

Then comes the years of gaslighting and retaliation that follows designed to make you quit… There’s nothing quite like that sort of experience of moral injury, pain, and confusion—and yet, even then, you try to see the good in an institution that is clearly rotten to the core until you can’t anymore.