I first became aware of the work of Drummond Rennie almost by accident: By borrowing his office. It was the summer of 1997, and as a rising fourth-year medical student, I was spending a month at JAMA as the co-editor-in-chief of its then-medical student section, Pulse. Rennie, who was deputy editor of the journal at the time, was mostly traveling, so the staff installed me in his office, overflowing with books and manuscripts.

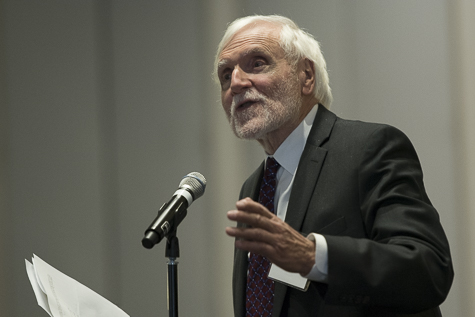

Rennie, who died on September 12, was a towering figure in scientific publishing. Trained as a nephrologist, he joined the staff of the New England Journal of Medicine in 1977, and later, JAMA, where he remained for decades. He was known for promoting improved standards in medical journals, and for organizing the first Peer Review Congress, held in 1989 and nine more times since, most recently earlier this month.

In 2013, we were just a few years into the work of Retraction Watch, and thought talking about what we’d learned so far at the Congress would be a good idea. We submitted an abstract outlining what we wanted to talk about, writing that we’d gather data by the time of the meeting.

That wasn’t going to work.

“We cannot go further unless we have some research in the form of data,” Rennie wrote to us in his characteristically sharp but highly constructive way. “The reviewers thought your abstract was pretty thin, and I agree. We know that you have the data and you have to think hard about what you are trying to say, remembering that the Peer Review Congresses were set up to present research, and not opinion.”

We ended up withdrawing the abstract because we didn’t have time to do the work that we agreed was necessary. But we also learned a lot, enough to be successful in being part of a few presentations in a later Congress. And we were always grateful when Rennie cited the work of Retraction Watch in calls for papers for the meeting.

Others will recount his work in other areas, but here, we wanted to share several passages of Rennie’s that illustrate his gift for a well-turned phrase in service of a sharp opinion or insight. Rest in peace, Drummond.

- Introducing the first Peer Review Congress, JAMA, 1986:

“There seems to be no study too fragmented, no hypothesis too trivial, no literature citation too biased or too egotistical, no design too warped, no methodology too bungled, no presentation of results too inaccurate, too obscure, and too contradictory, no analysis too self-serving, no argument too circular, no conclusions too trifling or too unjustified, and no grammar and syntax too offensive for a paper to end up in print.”

- “Editorial Peer Review: Let Us Put It On Trial,” Controlled Clinical Trials, 1992:

“And it’s true that bringing in the peers does seem to make the process more democratic, though most editors would dislike the idea that they were not benign despots. But editors, most of whose working hours are spent oiling, balancing, and tuning the mechanisms of peer review, have a conflict of interest: symphonic conductors would probably be as much in favor of the retention of orchestras.”

- On the then-short history of federal U.S. agencies tasked with investigating scientific fraud, writing with C. K. Gunsalus in JAMA, 1993:

“Scientists, however, seem to have been less able to accept the revelations than the general public, and a great deal less than members of Congress. Perhaps the difference can be explained by the fact that the Congress is composed largely of lawyers, who are not taught to trust easily. Our representatives correctly view themselves as custodians of the public purse and see plenty of evidence to counter the notion, seemingly prevalent among researchers, that scientific degrees endow their holders with the attributes of rectitude and honesty.”

- On the lessons of the Eric Poehlman case, writing with Harold Sox in Annals of Internal Medicine, 2006:

“The ORI has neither the mandate nor the resources to lead the task of correcting a scientific literature polluted by fraudulent research. This responsibility lies with the community of scientists. When an ORI investigation ends with a finding of misconduct, the work is just beginning. Following the investigation, the community must identify all of a fraudulent author’s articles, publish retractions, and rid the literature of references to the fraudulent articles.”

- “Integrity in Scientific Publishing,” an essay in honor of health economist Harold Luft, Health Services Research, 2010:

“I arrived at the New England Journal of Medicine in September 1977, at the same time as its new Editor-in-Chief, Dr. Arnold Relman. It took 4 months before we met our first ethical issue. A physician wrote to point out that, on the same day that we had published an article to show that patients with chronic paranoid schizophrenia had low levels of monoamine oxidase in their platelets (Berger et al. 1978), another journal had published an article to show that levels in such patients were the same as in normals and other schizophrenics (Potkin et al. 1978). She also pointed out that though neither article referenced the other, they had two authors in common. When we challenged the authors, they justified their practice by asserting that it was not their custom to refer to unpublished work in a publication. (Wyatt and Murphy 1978). They, and no one else, had possessed information that completely undermined both their publications, so this disingenuous claim demonstrated at the very least a startling contempt for the process of publication.

It was, for me at the New England Journal of Medicine, the first of many. Adopting Jules Pfeiffer’s phrase, I came to call such academic tricks ‘‘little murders’’—not deserving to be hanging offenses, but destructive of the delicate web of trust between colleagues that keeps the whole enterprise functioning and afloat.”

- “If you think it’s rude to ask to look at your co-authors’ data, you’re not doing science,” writing with C.K. Gunsalus in Retraction Watch, 2015:

“At a larger level, our question is this: if the coauthors cannot understand the data, how can the reader? Isn’t it the duty of those on the collaboration to understand it well enough to stand behind it?

We don’t wish to suggest that it is easy to fulfill the obligations of a co-author or mentor. In reality, given the complexities of interpersonal relationships and the trust science requires, it can be difficult and daunting. Still, it’s the job.”

Like Retraction Watch? You can make a tax-deductible contribution to support our work, follow us on X or Bluesky, like us on Facebook, follow us on LinkedIn, add us to your RSS reader, or subscribe to our daily digest. If you find a retraction that’s not in our database, you can let us know here. For comments or feedback, email us at [email protected].

Wonder what he would have said about the use of AI/ChatGPT to write papers! Or to do reviews of manuscripts and grant proposals… Am sure his tart comments would have been right on point.