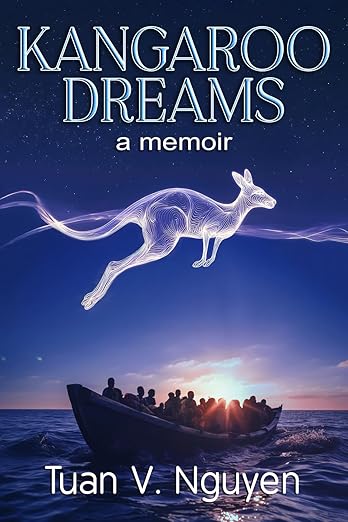

In a new memoir, Kangaroo Dreams, Tuan V. Nguyen, D.Sc., Ph.D., provides a unique perspective on medical research. Nguyen escaped Vietnam in 1981 as part of the mass “boat people” exodus of refugees, taking to dangerous waters just a few months after his older brother attempted the same and disappeared. Making his way to Australia through grit and luck in 1982, Nguyen started his new life as a dishwasher before steadily building a career in science, ultimately specializing in bone research.

Nguyen is now distinguished professor of predictive medicine and director of the Center for Health Technologies at the University of Technology Sydney and adjunct professor of epidemiology at the University of New South Wales. He’s also a Leadership Fellow of the Australian National Health and Medical Research Council and a member of the Order of Australia. Dedicated to the memory of his lost brother, Kangaroo Dreams weaves Nguyen’s personal journey with a thoughtful examination of contemporary medical research. We interviewed him in writing to learn more. (Responses have been lightly edited for length and clarity.)

Retraction Watch: You were co-author on a 1994 Nature paper subsequently corrected in 1997 which reported individuals with a particular vitamin D receptor gene benefitted from relatively high bone mineral density. When the research team made this finding, you write, “A nagging unease, however, bothered me. The results, while undeniably impressive, seemed almost too good to be true.” The team published the findings only to discover – after a Nature reader challenged the results – that a lab member who was ill likely contaminated samples, skewing the results. Did you regret not having pushed harder on your initial doubts? What held you back?

Nguyen: I come from a cultural background, particularly in Vietnam, where respect for teachers and senior colleagues is considered an ethical obligation rather than a matter of courtesy. This principle strongly shapes how junior scientists engage in professional discourse.

In retrospect, I sometimes wish I had expressed my reservations more directly. At the time, however, as a junior member of the team, my response was shaped by a strong cultural and professional norm of deference to senior colleagues, limited experience, and a good-faith expectation that the results would be independently validated through subsequent work anyway.

This experience became an important lesson for me in the need to actively insist on rigorous validation, particularly when findings appear unusually strong.

RW: Why did it take three years to publish a correction?

Nguyen: The reader’s question prompted a careful re-examination of thousands of original samples. Investigating the matter, including confirming the likely source of sample contamination and re-running the analyses, required time and thoroughness. This process was followed by internal discussions and coordination among the co-authors to ensure a shared understanding of the findings. The journal’s correction procedures also contributed to the overall timeline. Importantly, after the analysis was completed, the main conclusions of the study remained unchanged, which was a considerable relief for all of us. Once the evidence was clear and fully documented, we proceeded with the correction.

RW: Tell us briefly about the “experiment” you conducted which validated your suspicion about bias against papers authored by people with Vietnamese names.

Nguyen: At the time, I was running two research labs, one in Australia and one in Vietnam. In Vietnam, I had established a large, population-based prospective study with the support of many dedicated physicians and scientists. As this work progressed, I observed a recurring pattern: manuscripts from my Vietnamese lab received reviews that I regarded as unfair and unprofessional. Some were distinctly patronizing and, in certain cases, intimidating in tone. In some instances, reviewers raised statistically incorrect criticisms, even though I have extensive expertise in this area, having served as a professor of epidemiology and biostatistics and as a statistical editor for three medical journals.

In addition, some submissions were desk rejected with little or no explanation. Sometimes, the stated reason was that the work “added little to the literature,” despite the fact that these studies were genuinely novel. I also observed instances in which conceptually similar studies conducted in Western populations were subsequently published, while our previous work in Vietnam addressing the same questions with more rigor was deemed insufficiently original.

This prompted me to explore whether factors such as author affiliation or name recognition might be influencing editorial decisions. To do this, we submitted essentially similar manuscripts to the same journal, varying only the authorship. In the initial submission, all authors were based in Vietnam, and the manuscript was desk rejected. Several months later, a closely comparable version, now including my name and that of an Australian colleague, was submitted and was sent out for external review. At that point, we withdrew the manuscript and informed the editors of what we had done.

Although this was not a formal study, the outcome was consistent with my own experience and with broader discussions in the literature regarding unconscious bias in peer review, particularly as it relates to authors and institutions from lower-resource countries.

RW: We frequently report on paper mills, citation cartels and the like, and these often are located in developing nations. Do you think our reporting is adding to the bias, and what would you advise?

Nguyen: I have followed Retraction Watch with great interest for many years, as its reporting consistently reflects issues I have encountered firsthand in practice. Drawing in part on insights from your reporting, I have for 20 years raised concerns about research and publication ethics in Vietnam through the popular press and books written in Vietnamese.

I consider that your reporting is essential in uncovering genuine misconduct and in safeguarding the integrity of scientific research, irrespective of geography. That said, there is a possibility that sustained emphasis on particular regions may unintentionally reinforce certain perceptions or stereotypes, especially if comparable issues elsewhere receive less attention. For example, researchers in economically advanced countries also publish in predatory or questionable journals and engage in a range of questionable research practices, such as salami publication or p-hacking. Highlighting these issues across diverse settings can help ensure a more balanced and contextualized understanding of research integrity challenges.

So, my suggestion would be to continue this important work. At the same time, it may be helpful to place greater emphasis on the broader, systemic drivers of misconduct, such as publication pressure and incentive structures that operate across all research systems. Where possible, including more cases from high-income settings would add valuable context. Taken together, this broader coverage can help ensure that the focus remains on practices and structures, rather than on geography alone.

RW: In your book, you explore the dangers of narcissism to science. What do you think academics should do when they spot narcissism in a potential collaborator? In a detractor? In a mentee?

Nguyen: Over the course of my career, I have encountered many individuals with strong narcissistic traits in science. They can be intellectually stimulating colleagues, and some are undoubtedly highly talented. At the same time, these traits can present challenges in collaborative and mentoring contexts.

For potential collaborators, it is sensible to proceed with some caution. Reviewing their track record for equitable credit-sharing, collegiality, and ethical conduct can be helpful. If concerns arise, such as excessive self-promotion or a history of difficult collaborations, it may be wise to limit the scope of engagement or, if necessary, decline involvement.

For detractors, maintaining professionalism is the key. I find it helpful to focus discussions strictly on data, methods, and evidence, while documenting interactions and avoiding personal escalation. This approach helps keep disagreements constructive and protects one’s own position.

For mentees, early and thoughtful mentoring is particularly important. Setting clear expectations, modeling humility, and encouraging self-reflection can help channel ambition toward productive, collaborative outcomes. When left unaddressed, these traits can be detrimental not only to individuals but also to research groups and institutions.

RW: It has been very challenging to stop bad behavior in the sciences, partly because of the problem of self-interested institutions, as you note in your book. Do you suppose there should be some system for weeding out or at least being vigilant about problem personalities in the sciences? And if so, what would that look like?

Nguyen: I would be cautious about any formal mechanism designed to “weed out” individuals, as such approaches risk misuse and unnecessary punishment. A more constructive approach is to focus on systems and institutional culture, rather than on labeling people.

For example, institutions could strengthen anonymous and well-protected channels for reporting bullying or misconduct. They could provide regular training in research ethics and professional conduct. Broader forms of feedback, such as 360-degree evaluations, could also be incorporated into promotion and leadership decisions. In addition, greater transparency around conflicts of interest, particularly for reviewers and editors, would help build trust in the system.

In addition, I think professional societies and funding agencies can play an important role. They can recognize and reward behaviors that promote collegiality, integrity, and mentorship, rather than focusing exclusively on narrow performance metrics. In my view, lasting improvement is more likely to arise from sustained cultural change and shared accountability than from purely punitive approaches.

RW: Is there a role for overtly teaching humility in scientific training?

Nguyen: Yes, but it should be framed as a professional skill essential to scientific rigor, rather than as a moral trait.

In my cultural background, modesty and humility are considered professional and social norms. In other settings, however, humility may be interpreted as weakness, while overconfidence is sometimes rewarded as a sign of competence. In science, this inversion is problematic: overconfidence increases the risk of bias, discourages serious engagement with uncertainty, and can lead to premature or overstated conclusions.

For this reason, there is a strong case for giving humility more explicit attention in scientific training, alongside technical and methodological skills. Science advances through collective effort, and progress depends on recognizing uncertainty, fallibility, and the contributions of others. Humility, in this sense, underpins good judgment, reproducibility, and collaboration.

Early in my career, my institute director, a widely respected figure in DNA research, regularly reminded us to be modest and to share credit. This advice shaped my own approach to mentorship and is something I consciously pass on to my students.

Humility can also be addressed through structured training. In Vietnam, I have led workshops and seminars on research ethics and facilitated discussions of historical cases in which overconfidence or unrecognized bias led to serious scientific error. These settings allow trainees to see humility not as self-effacement, but as a safeguard against flawed reasoning.

That said, mentorship plays a central role in shaping scientific values. I was fortunate to train under a physician–scientist of exceptional integrity, who consistently modeled openness to critique, respect for replication, and a willingness to revise conclusions in light of new evidence. When demonstrated in practice, these principles are often absorbed more deeply than through formal instruction alone.

Thus, by treating humility as a core professional competency, essential to methodological rigor, we can strengthen both scientific outcomes and research culture.

Like Retraction Watch? You can make a tax-deductible contribution to support our work, follow us on X or Bluesky, like us on Facebook, follow us on LinkedIn, add us to your RSS reader, or subscribe to our daily digest. If you find a retraction that’s not in our database, you can let us know here. For comments or feedback, email us at [email protected].

I very much appreciate Dr. Nguyen’s insights into these important matters, especially his thoughts about teaching humility. I imagine that anyone, including a narcissist, can probably learn to act with humility. After all, narcissists are good at acting. However, are these characters ever able to develop genuine humility? And isn’t that what would be most desirable in a scientist?

Great point about presence of toxic/abusive people in academia.

Narcissists and psychopath people with dark personalities are perfect in manipulation and acting. They always have several masks in pocket, depending on situation, they change the mask. Some of these narcissists may have sadistic traits, need to irritate and bully somebody for no specific reason, just for enjoyment. It is obviously so hard and painful for a student or somebody else in a weaker position to work in such a hell toxic atmosphere.

As long as the institution benefits from that narcissist faculty, they ignore reports of abuse and misbehavior. Even, to support and protect their sick staff, the institution may shift blame to the abused person (student or a postdoc fellow), ending up some sort of unfair punishment, leading to long-term trauma, PTSD, etc.

The description of a lab member who was ill contaminating the data makes it sound like someone sneezed over some lab samples, and I had to reread this section several times.

I presume it actually means that the person altered or manufactured data due to personal circumstances of being unwell interfering with their ability to do their job or exercise their usual judgment.