Source: Instagram

In the string of prestigious awards Qusay Hassan, a mechanical engineer at the University of Diyala in Iraq, had received from the hands of his country’s minister for higher education and scientific research, the last two stood out: Each trophy carried the name and logo of the global analytics company Clarivate, a name seen widely as a key scholarly imprimatur.

The British-American firm runs the influential Web of Science Master Journal List, which it curates based on several quality criteria, and also calculates journal impact factors. The company says it takes retractions into account when calculating its highly coveted researcher designations.

But Hassan, who has had 21 papers retracted, was one of several Iraqi scientists and institutions winning accolades at the ministry’s high-profile Iraq Education Conference 2025 in Baghdad earlier this month. At the award ceremony on October 11, a deputy minister said a Clarivate team helped develop the selection criteria for the awards, which were based on Web of Science data. Like the other winners, Hassan received his two trophies from the minister, Naeem Abd Yaser Al-Aboudi, after a Clarivate representative announced his name from the stage.

In Iraq, where science has been struggling for many years and corruption is widespread, international praise carries extra weight. Many awardees were quick to trumpet their achievement online. As the University of Technology – Iraq, which won the “Distinguished University Award” among public institutions, stated on its website, “Clarivate is a reputable research institution that grants high credibility to research and academic efforts.”

But a deeper look reveals several award winners have tarnished publication records or are known to engage in unethical practices. The University of Technology, for instance, forces students to cite the school’s own journals if they wish to graduate, as we reported earlier this month, and asked them to cite the works of faculty members several years ago, according to a 2020 document posted on Facebook. The institution has the fifth-highest self-citation rate among the 1,500 most-published universities in the world, an analysis using Clarivate’s own data shows. (Topping that list is the University of Mosul, also in Iraq.)

Hassan, who won a “Distinguished Researcher Award” and a “Distinguished Research Award,” has earned 21 retractions since last year. Many were due to unauthorized authorship changes after a manuscript was accepted, a hallmark of paper mill involvement, and some articles had content that was clearly stolen.

In 2024, Hassan was directly linked to a paper mill operation in an in-depth investigation by the scientific sleuth Nick Wise, who is now a research integrity manager at the U.K. publisher Taylor & Francis. The article that earned Hassan the “Distinguished Research Award” – “The renewable energy role in the global energy Transformations,” published in Elsevier’s Renewable Energy Focus and cited more than 800 times, according to the website – itself was likely the product of a paper mill. A day after it was accepted, but before publication, a “Dr. Ali Khudhair” mentioned the work in a chat in a paper mill group on WhatsApp that Wise has posted online. “Congratulation [sic] my co-authors,” Khudhair wrote, adding, “Kindly, prepare for payment.”

Several academics told us they were taken aback by Clarivate’s involvement in the awards.

“This is mind-boggling to me,” said Lokman Meho, a university librarian and professor at the American University of Beirut in Lebanon, who has developed an index to flag potential research-integrity problems at universities across the world. Clarivate is “partnering in academic crime.”

An Iraqi scientist, who asked to remain anonymous for fear of retaliation, said: “This is a complete failure of due diligence by Clarivate.”

The firm announced in July it had entered into a “landmark agreement” with Iraq’s Ministry of Higher Education and Scientific Research, which has worked for years to combat predatory journals and boost the rankings of its universities and scientific journals. “The objective is to improve the authenticity, credibility, and global visibility of research produced in Iraq, aligning with the country’s national priorities for innovation, development, and academic excellence,” Clarivate wrote on LinkedIn. Several Arab-speaking company representatives participated in the Baghdad conference and gave talks.

In an emailed statement, the company distanced itself from the Iraqi accolades. “The awards presented at the Iraq Education Conference 2025 by the Ministry of Higher Education were informed by data from the Web of Science, though they were not formally accredited by Clarivate,” a spokesperson told us.

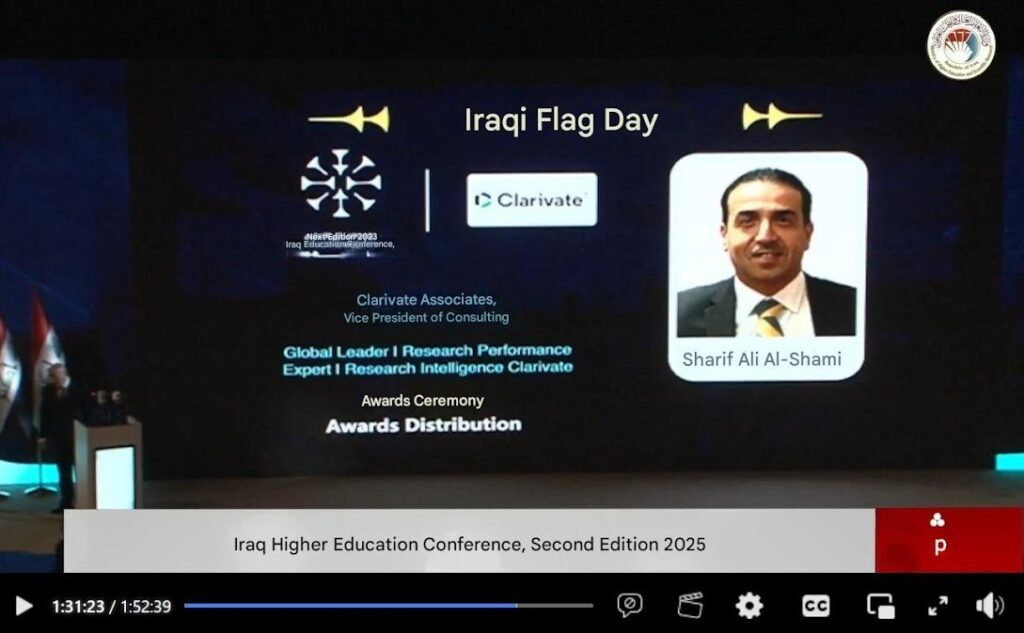

During a presentation by Deputy Minister Hayder A. Dhahad at the trophy ceremony on October 11, a video of which was posted on Facebook, a slide in Arabic claimed “accreditation” of the awards by Clarivate “for the first time in the history of Iraqi higher education.” Dhahad explained the company had worked with the ministry to develop a model to select the award winners. Then Sharif Ali Al-Shami, described as a vice president at Clarivate, read out the names of the winners as they or their representatives walked onstage to receive a trophy bearing the company’s name and logo.

In a news release about the awards, the president of the University of Technology was quoted as saying what made them so special was that they had been “accredited by the international Clarivate Foundation for the first time in Iraq’s history.”

Clarivate would not say whether it had approved the use of its name on the trophies, nor answer questions about how much its contract with the Iraqi government was worth. Neither the Ministry of Higher Education and Scientific Research nor the University of Technology replied to requests for comment.

“When awards carry the name or endorsement of a global organization like Clarivate, they carry an implicit promise of credibility and trust,” said Maryam Sayab, director of communications at the Asian Council of Science Editors in Dubai and co-chair of the Peer Review Week Committee.

“In that context, recognizing individuals or institutions with documented integrity concerns is troubling, not only for the local academic community but also for the credibility of the award itself,” Sayab added, noting that she spoke in her personal capacity.

Hassan asked us to “refrain from publishing any article or photograph involving me,” as his “university may terminate my position and I may lose any chance of future employment in Iraq.” Although he is seen receiving two awards in the video from the ceremony and is pictured holding a Clarivate-engraved trophy on the ministry’s website, Hassan denied getting “any awards from the Iraqi Ministry of Higher Education and Scientific Research that were presented in cooperation with Clarivate, such as the Science Day Award or the Iraqi Flag Day Award.”

Hassan has received at least three previous awards for his research. Each time, Al-Aboudi presented the trophy.

“In my opinion, metric-based recognition without integrity screening can inadvertently legitimize problematic practices,” Sayab told us. ”That risk is particularly acute in environments where publication is tied to career progression but where research funding, infrastructure, and oversight remain weak. These conditions can – and often do – fuel paper mills, coercive citation policies, and other unethical behaviors.”

Iraq’s research output has been soaring under pressure from both government and university officials eager to see their institutions climb the rankings. Steep publication requirements are standard for both faculty members and students. But with just 0.04% of Iraq’s gross domestic product, or around US$84 million, going toward research and development, insiders say it’s difficult to do the work needed for bona fide publications.

“The real damage came from mixing universities with politics, it created failed leaders chasing fake achievements through fraud and fabrication,” said the Iraqi scientist who spoke on condition of anonymity.

“The ministry keeps raising publication requirements for evaluations and promotions, but provides zero funding for research,” the scientist added. ”Most MSc and PhD students end up doing their work outside their universities because there’s literally nothing inside: no infrastructure, no funding, no labs, nothing. Many resort to offices with shady deals to get their work done.”

Over the past two months, we have written about high-placed academics in Iraq – a university dean, Yasser Fakri Mustafa, and Dhahad, the deputy minister, who is also a university professor – who lost several articles with signs of paper mill involvement. We have also covered widespread coercive citation at Iraqi institutions and a massive publishing scam that defrauded budding researchers of hundreds of thousands of dollars.

A researcher at an Iraqi university told us the country’s recent publishing craze, combined with the lack of funding and infrastructure, has fostered a bustling underground economy, often to the benefit of senior academics.

“It’s like a cake they are dividing,” said the academic, who also spoke on condition of anonymity.

Academic power brokers may host conferences offering paying participants a chance to publish, for example, or, worse, be at the center of authorship-for-sale networks.

“Now we have many offices for paper mills in Iraq,” said the academic, who also spoke on condition of anonymity. “Many of these offices are actually established and started by people who are decision-makers – certain profs, certain deans, certain heads of departments. Now it’s become like a trade.”

The unethical publishing practices are reflected in the Research Integrity Risk Index developed by Meho, the university librarian in Beirut: Among 18 Iraqi institutions, 12 are red-flagged for “extreme anomalies” and “systemic integrity risks.” Al-Mustaqbal University in Hilla, which won the “Distinguished University Award” among private institutions at the Baghdad conference, has the third-highest retraction rate of the world’s 1,500 most-published universities, for example. The institution did not reply to requests for comment.

“I feel sorry for the Iraqi people,” said Meho. “They are being misled” by their government, their universities and Clarivate.

But Meho was quick to note bad research practices are common elsewhere, too. “Several countries are doing this, and they are harming themselves.”

To move forward, observers say Iraq has to put the horse back before the cart and work on research infrastructure and integrity instead of focusing blindly on publication metrics and rankings.

”Real progress comes when transparency is combined with credible integrity checks, disqualification mechanisms, and structural reforms that address the root causes driving unethical publishing,” said Sayab.

Like Retraction Watch? You can make a tax-deductible contribution to support our work, follow us on X or Bluesky, like us on Facebook, follow us on LinkedIn, add us to your RSS reader, or subscribe to our daily digest. If you find a retraction that’s not in our database, you can let us know here. For comments or feedback, email us at [email protected].

An example of a country trying to catch up in a game not invented by themselves. With zero appreciation of the spirit of this system, they do everything to game the metrics.

To be fair, academics in Western countries have lost their appreciation of the spirit of this system, too. It’s just easier for them to game the system, so they are caught less. One of the reasons I left my tenured position.

Finally someone’s calling out the emperor with no clothes!

This is exactly what’s been eating away at Iraqi academia from the inside. When you mix politics with universities, you don’t get better science, you get a fox guarding the henhouse. These so-called leaders are just chasing shiny trophies while the whole system rots underneath.

Kudos to Retraction Watch for shining a light on this mess

This is journalism that actually matters

The irony? Clarivate slapping its name on awards for people with 21 retractions. That’s like putting a “quality seal” on counterfeit goods. No wonder honest researchers in Iraq feel like they’re swimming against the tide.