Systematic research fraud has outpaced corrective measures and will only keep accelerating, according to a study of problematic publishing practices and the networks that fuel them.

The study, published August 4 in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, examined research fraud carried out by paper mills, brokers and predatory publishers. By producing low quality or fabricated research, selling authorship and publishing without adequate quality control and peer review, respectively, these three groups were well known to produce a large volume of fraudulent research.

“This is a great paper showing how much fraud there is in the scientific literature. The paper also looks at different methods on how to detect problematic papers, networks and editors,” Anna Abalkina, a researcher at Freie Universität Berlin and creator of the Retraction Watch Hijacked Journal Checker, said.

Researchers and journalists have been looking into paper mills for more than a decade, as they have affected multiple publishers over the years, even before the high-profile retractions of thousands of articles from Hindawi journals.

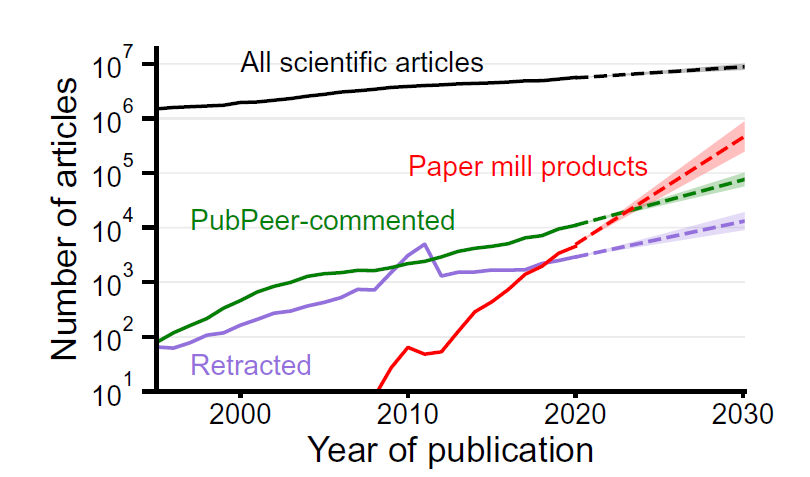

The latest study confirms the large volume of suspected paper mill products have been doubling more than twice as fast as corrective measures — both official measures like retractions and unofficial channels like the number of crowdsourced comments flagging problematic papers on PubPeer.

“It’s like emptying an overflowing bathtub with a spoon,” coauthor Luis Amaral, a professor at Northwestern University, told us.

To combat this systemic fraud, the researchers call for a global change in research incentives.

Case studies

To look at cases of paper mill activity to inform their larger network design, Amaral and a research team of metascientists examined metadata from the journal PLOS One, and DOIs from IEEE conference proceedings, along with the Retraction Watch Database and PubPeer comments to compile networks of editors who were significantly more likely to accept articles that eventually got retracted or flagged for concern. (Disclosure: Our Ivan Oransky is a volunteer member of the PubPeer Foundation’s board of directors.)

PLOS One has been a known target of paper mill activity in the past. Amaral and colleagues identified networks of editors who accepted an abnormally high rate of papers that were later retracted. The 45 editors implicated in this network edited 1.3 percent of all articles, but 30.2 percent of all retracted articles. More than half of the editors also authored articles that were later retracted.

Renee Hoch, head of publication ethics at PLOS, told us that since the increased paper mill activity was detected four to five years ago, the company has implemented measures to investigate existing articles and paper mill networks, and thoroughly screen new papers, authors and editors before publication. Even before then, the publisher had expanded its publication ethics team to investigate papers.

“PLOS was used as a data source in this study in part because PLOS publishes all of our articles Open Access, we list the names of handling editors on our articles, and we allow bulk access to our article content and metadata,” Hoch said. “However, the issues that surfaced in this article are not specific to PLOS One and instead are affecting journals and publishers across the industry.”

The researchers conducted the same analysis on papers from Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers (IEEE) conference proceedings, which have long been a known target for paper mill activity. They found hundreds of conferences produced abnormally high proportions of papers that were later retracted, flagged on PubPeer, or flagged for using tortured phrases. Seven of these conference series were flagged every year the conference was held.

“We believe our preventive measures and efforts identify almost all papers submitted to us that do not meet our standards,” an IEEE corporate spokesperson told us. “To adhere to our standards, IEEE continuously inspects our digital library and acts accordingly when we become aware of possible issues with content, takes the appropriate level of care and time in our review, and, if necessary, retracts nonconforming publications.“

In addition to looking at individual journals and publishers, Amaral and colleagues used large databases such as Scopus and Clarivate’s Web of Science, along with PubPeer comments about suspected image duplication to map a network of papers across many large publishers like Springer Nature, Spandidos, Wiley and Elsevier. They found multiple clusters of duplicated images that seemed to be published close in time. Of papers with suspected image duplication, 34.1 percent have been retracted.

The authors’ approach of looking at image duplication networks is innovative and had not been done before, Abalkina said. “It is fascinating to see how paper mills expand like [an] octopus engaging more and more scholars in the network.”

Amaral and colleagues also analyzed the impact of fraud on certain subfields, focusing on RNA biology, which study coauthor Jennifer Byrne of the University of Sydney and others have closely examined for years. The researchers found compromised subfields had a retraction rate around 4 percent, while uncompromised ones remained lower, at about 0.1 percent.

And the researchers quantified journal hopping using a known paper mill broker, the Academic Research and Development Association (ARDA), which some of the study coauthors described in detail last year for Retraction Watch. ARDA’s website listed journals in which the organization guaranteed publication. As the listed journals were de-indexed from Scopus (at a much higher rate than other journals – 33.3 percent versus 0.5 percent), new journals would be added to the list.

Despite publishers’ current efforts, the researchers calculated that only 28.7 percent of suspected paper mill products have been retracted. The figure came from the researchers’ dataset of paper mill products and the Retraction Watch Database, using data through 2020, although data show paper mill growth since then has been rapid. They extrapolated from current trends that “only around 25 percent of suspected paper mill products will ever be retracted and that only around 10 percent of suspected paper mill products will ever reside in a de-indexed journal.”

These numbers likely underestimate the full extent of the problem, because they “rely on the instances of scientific fraud that have been reported,” they wrote in the paper.

What can be done?

Amaral compared the scale of the issue to combating the ozone hole over Antarctica, and said that the scale of the solutions need to match. “We need the biggest, most important stakeholders of science to come together to talk about what needs to be done, what standards need to be implemented and not wait for the problem to solve itself,” he told us. He named national organizations like the U.S. National Academies, the Chinese Academies of Sciences, and the U.K. Royal Society as stakeholders big enough to influence large organizations like publishers to act.

“They need to implement decisions, and they need to advocate strongly for those decisions to be adopted by journals, by funding agencies, by employers, universities, the national labs,” Amaral told us. “It’s not going to be an individual choice.”

However, individuals can play a role in advocating for change. Anyone can “press on policymakers to end the culture of hyper-competition in science,” Reese Richardson, a coauthor of the study and a postdoctoral researcher at Northwestern University, told us. “Scientists are all competing against each other for an increasingly scarce pool of resources,” he said.

Scientists can help address the problem in additional ways, Richardson told us. “What scientists can do in their own personal capacity is do post-publication peer review, and take a critical eye to the literature in their fields because it’s clear that we’re only detecting a tiny, tiny fraction of the problem,” he said.

He also suggested researchers develop “high throughput approaches to identify problematic articles” and metascientists “can use rare signals, like the comments that people leave on PubPeer observations about image misidentification and image duplication and instrument misidentification, tortured phrases … to understand what’s happening behind the scenes. That’s the job of meta scientists – to use public visible indicators to get at what’s invisible.”

We’ve covered a number of these high throughput approaches in the past, including one Richardson and Amaral developed with others to detect papers that misidentify microscopes used in their studies.

“We are part of a community that has been fighting for recognition of something that has been concerning us,” Amaral told us. “We are grateful for everything that everyone else has done, and to be a part of that, because science is very important to us and we want to do things to maintain the ideals of what science should be.”

Like Retraction Watch? You can make a tax-deductible contribution to support our work, follow us on X or Bluesky, like us on Facebook, follow us on LinkedIn, add us to your RSS reader, or subscribe to our daily digest. If you find a retraction that’s not in our database, you can let us know here. For comments or feedback, email us at [email protected].

It’s worse than that. Most fraud will never be detected because journals don’t require submission of raw analytical data. Just assume everyone is lying unless separate groups have reached the same conclusion.

“unless separate groups have reached the same conclusion.” — even this provides no certainty — contradicting results are very hard to publish (are in essence unpublishable), especially if the original findings appeared in a “high impact” journal. So, then only confirming work (whether accidentally or “by design”) is published, and the original producers of the questionable conclusions can claim “look, many groups could reproduce our findings”…

A lot of these results are obtained from underpowered studies, so repeating the study and not finding a result with a replicate study doesn’t mean anything. The best idea for a researcher is to obtain funding for a larger well done study for some other outcome and include the suspicious one as a secondary outcome.

That’s quite funny. The journal the study is published in, PNAS, has a nickname, Probably Not Actually Science. I believe the credit for that observation should go to “Owlbert”.

To look at cases of paper mill activity to inform their larger network design, Amaral and a research team of metascientists examined metadata from the journal PLOS One […] to compile networks of editors who were significantly more likely to accept articles that eventually got retracted or flagged for concern.

By the way, what is the difference between a corrupted editor and the PNAS contributed track ?

Reese Richardson ““We need the biggest, most important stakeholders of science to come together to talk about what needs to be done, what standards need to be implemented and not wait for the problem to solve itself,” he told us. He named national organizations like the U.S. National Academies, the Chinese Academies of Sciences, and the U.K. Royal Society as stakeholders big enough to influence large organizations like publishers to act.”

There are conferences like this galore, where the editors of the most prominent journals get up on the podium and talk and talk about scientific integrity, but in fact, deflect any criticism of what is on the pages of their own journal.

Those are the Establishments for more, and less democratic countries. Members will be very unlikely to alter the path to how they got to the top for fear of what might happen to them. I’m not sure than these Establishments are big enough to influence large organizations like the publishers to act. The large publishers have the money, pots of money, from time to time they may dole out some of the money to the national academies of science, provide a few thousand dollars here and there to fund a summer studentship, but we must be mindful that they make very large profits and have led to Retraction Watch coming into existence. Governmental action may be required. Too many retractions and the publishers lose their licence to publish in that jurisdiction. Would Elsevier really leave the Netherlands and move to Panama, or Liberia? Would Nature really leave London? Too many retractions and the institution incurs penalties. Problem is that a combination of pots of money and woke will get in the way.

Example. https://www.nature.com/articles/d41586-025-02364-6#:~:text=India's%20national%20university%20ranking%20will,of%20retractions%20due%20to%20misconduct.

That appears in Nature, which itself is resistant to correcting, or retracting problematic data within its own pages. Paper mills are problematic, but we mustn’t for get that the main publishing houses are problematic too, it’s their business.

Examples:-

https://pubpeer.com/publications/3620BA59CC17B5DB62215DD774D352

https://pubpeer.com/publications/31695E23BA9C15556E5D6B8CEA931B

https://pubpeer.com/publications/85F80C559B2462A008E39A98789357

The Science report on this paper mentioned medical students applying for residency to be incentivized to use paper mill services. I can relate to that as my wife is in her third year of medical school and is already worrying about not having time to do research.

It is absurd to expect medical students to do extracurricular stuff like reseach, let alone making publication (semi-)mandatory for residency application. MD program and PhD program are separated for some reason. If PhD students are not required to do rotations in hospitals, I don’t see why MD students are required to do research.

MD curriculum is intense, and people have different levels of energy, some are already exhausted by the mandatory training. It’s unreasonable to force people to pursue the limitless publication-stacking. As there is no cap on the amount of publications (and on record it might not be mandatory, though everyone knows it is), everyone knows it’s the more the better.

This is stupid, research output is not at all an indicator of a physician’s capability, and patients very likely don’t care about how good a doctor is in research. Medical students themselves probably don’t care about the research either, they are always seeking the most efficient way to churn out the most papers. Doing a simple t-test and publish a two-page something, for example.

If no one really care about what is being published (except for the residency match maker? recruiter? I don’t know the correct term), and publications only serve as a threshold to get pass, an index to stack, then, why not use paper mill?

I personally don’t mind at all if my doctor has 100 retracted papers as long as they can give accurate diagnosis. Actually, I didn’t even know doctors are required to do research before my wife talked about her medical school life.

This is absurd. Abolishing the requirement of research for residency matching can eliminate one source of clients for paper mill services.

The problem is not just “papermills”. The big publishers are making massive profits from publishing, as can be seen from the aquisition and launch of Nature on the share market by a venture capital company. Their incentive is to publish as much as possible and advertise it widely with “new research” (for downloads). Why do we pay $3000 or more to publish an article that probaly costs $150 to put on an institute website? We used to use society published journals and Institute published Bulletins and Reports that were circulated by librarians. The cost was minimal and “in house” – Why did we change?

Another hidden problem is that of big drug and herbal supplement companies that encourage (mass produce?) papers approving the use of their product, and discouraging and blocking work or sueing authors and publishers who question the efficacy of their drug.. For example, note the removal of a paper by Elsevier in 2019 “for legal reasons” following a complaint from Herbalife. An afternoon chasing down the owners and activities of Herbalife and its products/papers is quite revealing, but they are just one example.

Yes… the perennial mystery: what is the cost of publishing scientific articles that justifies the outrageous APC? How is the APC used? It definitely doesn’t reward the reviewers for their hard work. And I don’t think the editors, who did almost nothing other than sending emails, worth that much salary. Where does this money go?

Do you know what an editor does? Do you know what a copyeditor or proofreader does? An IT person who gets your article posted online and indexed on PubMed? Or someone who gets the metadata right so your article can be read online? Do you know what a graphics person does, the one who makes your figures look nice and fixes the typos? How much does a web platform cost, one that hosts your article and everything else the journal publishes? Maybe that’s where the APC goes, among many other places.

Publishing articles is not done through magic. It is done through the efforts of people just like the ones who write and review articles.

If you assume a 50% reproducibility rate (results from reproducibility projects vary from 12-61%), the line of irreproducible articles would be just below the “all articles” line in the logarithmic plot.

Just as a comparison to the red “paper mill products” line…

To IEEE’s defense: it is still a professional society, and thus discrimination against certain countries from which almost all paper mill products come cannot be done. That said, I think they should flag and block certain conferences and their committees that are well-known to be problematic. The paper mill spam is really lowering the quality and usefulness of their electronic library too, so they really should have a self-protective incentive to do something. And as ACM decided to go full OA, many quality venues will likely switch soon too.

I submitted an EthicsPoint complaint about a number of IEEE proceedings on June 9th. Still today almost two months later, no progress, no investigation, no response to initial complaint, no response when more info supplied and update requested.

It seems that IEEE just doesn’t respond/ignores ethics complaints through it’s officially endorsed route. It isn’t just preventive action that is the problem, corrective action is lacking too.

Why bother emptying the bathtub when you can just ignore it? Don’t cite authors who publish with papermills, don’t subscribe to journals that publish papermill slop, and wherever possible take steps to frustrate/defund/deplatform them. Those who use publications as markers of researcher quality should be obliged to perform due diligence the same as a banker granting a loan. If a CV contains a stinker, the candidate goes to the bottom of the pile. As for counteracting the toxic effects of papermill slop on science, the primary defense has always been the same: a fully functional bullshit detector.

The problem with ignoring the bathtub individually is that other people might not. And when these other people are effectively in charge, we have a problem.

It is also our responsibility, as scientists, to clean up our “production” so that informed decisions are not based on spurious evidence.

Many make fun of those who do not believe in evolution, some even make a living out of making fun of those who do not believe in evolution, but how come many scientists are either very slow to realise, or still do not believe, that evolution applies to them?

The full and inexorable horror is clearly laid out here:

R Soc Open Sci . 2016 Sep 21;3(9):160384. doi: 10.1098/rsos.160384. eCollection 2016 Sep.

The natural selection of bad science

Paul E Smaldino 1, Richard McElreath 2

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/27703703/

“Selection for high output leads to poorer methods and increasingly high false discovery rates. We additionally show that replication slows but does not stop the process of methodological deterioration. Improving the quality of research requires change at the institutional level.”

I do not see change at the institutional level happening any time soon except for requiring more and more.