SA Memon et al/Nat Hum Behav 2025

Several studies have tackled the issue of what effect a retracted paper has on a scientist’s reputation and publication record. The answer is, by and large, it depends: The contribution the researcher made on the paper, their career stage, the field of study and the reason for the retraction all play a role.

Three researchers from New York University’s campus in Abu Dhabi wanted to better understand how a retraction affects a scientist’s career trajectory and future collaborations. Using the Retraction Watch Database, they looked at papers retracted between 1990 and 2015, and merged that data with Microsoft Academic Graph to generate information on researchers’ pre- and post-retraction publication patterns, as well as their collaboration networks. They also looked at Altmetric scores of retractions to factor in the attention a retraction got.

From that data, they extrapolated if and when researchers with retracted papers left scientific publishing, and looked for trends in researchers’ collaboration networks before and after the retraction.

Shahan Ali Memon, Kinga Makovi and Bedoor AlShebli wrote the article, “Characterizing the effect of retractions on publishing careers,” published in April in Nature Human Behavior. We asked them about their research, their findings and the inspiration for the study.

Questions and answers have been lightly edited for clarity and brevity.

RW: Your study looks across all disciplines. What trends did you find? And what differences did you find among the fields of science?

Memon: Our analysis centered on STEM, particularly the natural sciences, and revealed a consistent pattern across fields: Retracted authors who remained in publishing careers retained and gained more collaborators than their matched counterparts who did not have retractions, with the largest gaps appearing in biology and medicine.

RW: Of the researchers with retractions in your dataset, how many left science? What trends did you find in that data?

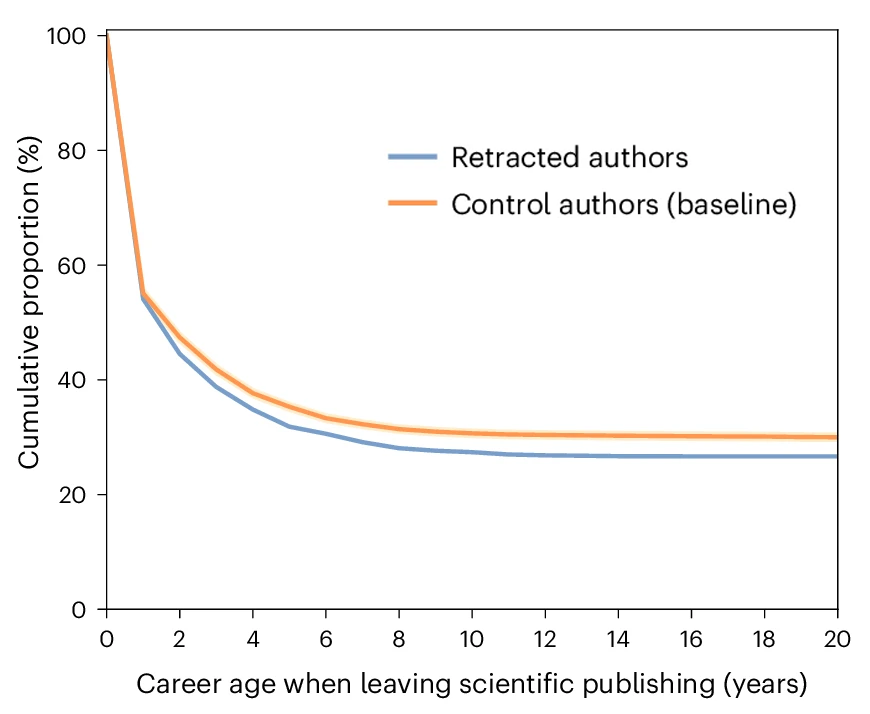

Memon: We found that about 46% of the retracted authors leave their academic publishing around the time of the retraction, and that the early-career authors, those whose papers are retracted due to misconduct and plagiarism, and those with higher online attention were more likely to leave when experiencing a retraction.

We found that the retracted authors who remained in publishing careers did not suffer a reduction in the size of their collaboration networks post-retraction; instead, they built larger collaborations than their counterparts. However, this increase in size – both retaining more old and creating more new collaborations – was accompanied by qualitative differences, with retaining less senior, less productive and less impactful collaborators, which was balanced by gaining more impactful ones.

Note that these are the broad contours of the results and rely on averages using all fields and academic ages of authors. When we disaggregate these analyses by, say, seniority of retracted authors, we don’t find these patterns in all cases, but overall, these trends describe the results in broad strokes.

RW: How do you account for the growth of collaboration networks for researchers who have retracted their work and continued to publish? We have written in the past about “trust dividends” that seem to accrue to researchers who retract for honest error. Is the same thing at work here?

Makovi: This is a great question, which our data can not address directly, and where qualitative work and future research would be helpful. Here are two hypotheses, which address this question from either the supply or the demand side of collaborators.

On the demand side, retracted authors might change their strategy in seeking collaborators. Specifically, prior research has documented that having a retraction might have a stigmatizing effect, and as we and others have shown, has negative impacts on various career outcomes. To counteract these, some retracted authors might act particularly agentically seeking collaborators to increase the volume and impact of their work.

The supply side may be how the environment around the retracted author changes: Senior colleagues in one’s department might become especially agentic in bringing retracted authors on as collaborators, especially if their retractions were due to a mistake, and/or if the retracted author experienced a retraction early on during their career. They might broker connections to help them along.

Both of these remain hypotheses that we are unable to test with the data at hand. There could be other explanations as well, therefore, we would take this explanation with a heap of salt, as it points beyond the analysis we conducted in the paper.

RW: Were you able to tease out whether specific authors in your dataset had responsibility for the factors that led to retraction? And were you able to observe and study a “bystander effect”?

Makovi: This is an excellent question, and I wish we had a straightforward answer. As part of our analysis we trained a large group of students to identify and hand-code retraction notices to categorize retraction reasons, and collect other data, for instance if the retraction was led by authors or journal editors. In the process we have read many retraction notices ourselves. It is a rare occasion that the notice doles out responsibility to specific authors. We only found a handful where this was the case.

What we have done is a disaggregation of our findings by author position, separating first, last and middle authors, which correlate with the typical roles in a paper, but we would not find it convincing to base “responsibility” on this. This, again, is an aspect where more qualitative work would come in handy.

RW: Your study focuses on papers retracted between 1990 and 2015, and includes data up through 2021. Since then, the number of papers has gone up and so has the retraction rate. How do you think things may have changed since your analysis and since the cutoff of your datasets?

AlShebli: We focused on this period to allow for a long enough observation window, up to five years after retraction, to assess career outcomes like collaboration patterns and attrition. Since then, several dynamics may have changed. For one, there’s been increased awareness and transparency around research integrity, and platforms like Retraction Watch have expanded coverage, possibly shifting the norms around retraction and its stigma. At the same time, with the rise of open science and preprints, new challenges around reproducibility and misconduct have also emerged. Not to mention the newly available AI tools that might shape how authors write, cite and conduct research more generally. These changes could affect both the frequency of retractions and how they impact scientists’ careers.

That said, while the scale has grown, we believe that many of the structural dynamics we document, like career attrition or collaboration loss, might still hold today. We hope future research, using newer data, will build on our findings to track how these patterns evolve over time.

Retraction Watch: Two of you (AlShebli and Makovi) had a paper retracted, which you mention in a note at the end of the paper. How did that experience inform this study?

AlShebli: Yes, two of us experienced a shared retraction firsthand, and we felt it was important to be transparent about that in the paper. That experience gave us a personal understanding of how painful and disorienting the process can be. We were very fortunate to have strong support from our colleagues and peers, which helped us recover and continue our research. But our experience, as the data shows, could have been very different.

That contrast really motivated this study. We wanted to understand how retractions affect scientists more broadly, especially early-career researchers, and to highlight the structural factors that can either mitigate or exacerbate the impact. Ultimately, our hope is to inform an evidence-based approach to research integrity that is perhaps more compassionate.

RW: How can scientists help early-career researchers move beyond a retraction?

AlShebli: Retractions are a necessary self-correcting mechanism of science and scientific progress. They are meted out collectively, and as an institution, we do not believe that retractions should be done away with. The challenge lies in communicating what they mean to the public, and to fellow scientists. Our findings highlight just how vulnerable early-career researchers are in the wake of a retraction. They face higher rates of career attrition which can derail promising trajectories.

One possible takeaway is that institutions, funders, and senior collaborators need to be more proactive in distinguishing between culpability and proximity. When early-career scientists are caught up in retractions they didn’t cause, they need support systems, such as mentorship, opportunities to re-establish their credibility, and clear institutional statements where appropriate. Transparency in responsibility and a culture that allows for recovery, rather than guilt by association, are crucial to protecting the next generation of researchers.

Like Retraction Watch? You can make a tax-deductible contribution to support our work, follow us on X or Bluesky, like us on Facebook, follow us on LinkedIn, add us to your RSS reader, or subscribe to our daily digest. If you find a retraction that’s not in our database, you can let us know here. For comments or feedback, email us at [email protected].

I have to think that if you can’t separate retractions for which the individual is blamed from ones for which they aren’t–I suspect the community knows even if the retraction notice doesn’t say–the data will be awfully muddled.