Haunschild & Bornmann/arXiv.org

While using bibliometric techniques to measure how disruptive research papers are to their field of study, Robin Haunschild and Lutz Bornmann stumbled across a strange phenomenon.

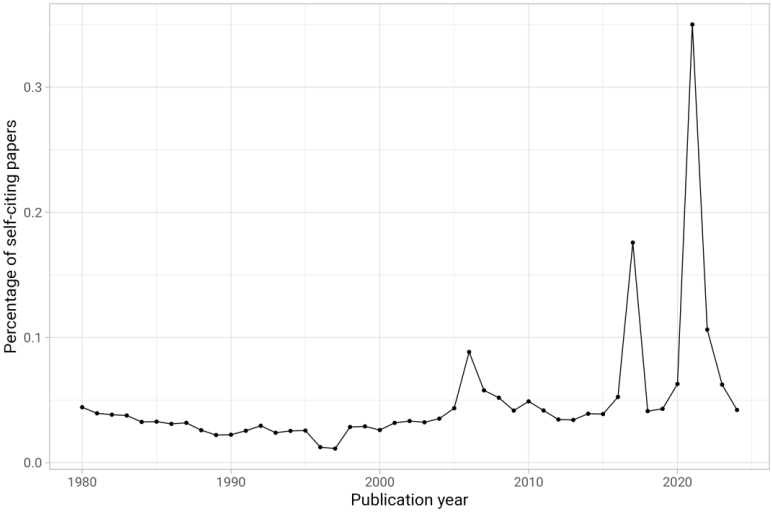

Just under 45,000 academic papers contained citations to themselves, they found. Haunschild and Bornmann — both information scientists at the Max Planck Institute for Solid State Research in Stuttgart, Germany — found these “paper self-citations” in journals indexed by Clarivate’s Web of Science since 1980.

Some 7,943 different journals had at least one self-citing paper, the researchers report in their study, posted on arXiv.org earlier this month. Eight journals alone covered 10% of the sample papers, and 129 publications covered the top third. More than 31,000 of the papers appeared under the ‘article’ category in Web of Science, followed by just over 6,000 listed as ‘corrections’ and just under 2,500 as ‘reviews.’

Stéphane Bonhomme, an economist at the University of Chicago who edits Quantitative Economics — the journal with the highest number of paper self-citations in study, 165 self-citing papers out of 416 studies in total — says he was surprised to see the numbers for his publication.

But after taking a closer look, Bonhomme said, he discovered that many paper self-citations were coming from the authors referencing their own appendices and supplementary materials that were published under different DOIs — a fairly common practice in economics, particularly with papers with long appendices or supplementary material.

“It’s supplementary information which is completely related to the paper, but it’s not part of the published paper,” Bonhomme told us. “My conjecture is that this is most or all of the [paper] self-citations for this particular journal.”

Authors based in the United States had the highest number of paper self-citations at 13,128, followed by those based in China at 5,363, and the United Kingdom at 4,493.

From the study, it seems that around half the papers self-citations in the sample are the result of database errors, said Molly King, a sociologist at Santa Clara University in California. King published a large-scale analysis finding men cite themselves an average of 56% more than women do.

King said she would like to see a larger sample that explores how many studies contain true paper self-citations versus how many are the result of mistakes in the database. “That’s the remaining question in my mind,” she said. “How much of this is a Web of Science problem, and how much of this is actually happening in the real world?”

Some true self-citations may indicate researchers or journals trying to game the system to boost their citation counts, said Bornmann, who is also a sociologist of science at the Max Planck Society in Munich. Bornmann said he’s not aware of any guidelines for authors or journals on paper self-citations. The next step would be to explore the reasons behind this trend, he said.

“Given the very low percentage of it happening, it’s possible there’s a few scholars out there who have uncovered this as an approach to artificially inflating their citation indices,” King said. “But it does not seem to me like this is anything approaching a widespread gaming of the system.”

This story was updated on March 24 to correct Molly King’s affiliation.

Like Retraction Watch? You can make a tax-deductible contribution to support our work, follow us on X or Bluesky, like us on Facebook, follow us on LinkedIn, add us to your RSS reader, or subscribe to our daily digest. If you find a retraction that’s not in our database, you can let us know here. For comments or feedback, email us at [email protected].

Sometimes earlier results are referred without increasing length of paper. Five temperature midel may require your 4 temp midrl if any …. simple self citation to increase citations bad thing.

I wonder how one would even do this. When I submit a manuscript, the bibliographic information to cite that mansucript doesn’t even exist. No DOI has been assigned, no journal issue or page number has been assigned yet. The journal staff would need to be involved …

The article appears hastily written.

It’s not making a very clear distinction between author- and paper- self-citation. Rather poor standard for a RW article.

No, obviously they’re not saying a paper somehow cites itself, in a loop. They’re saying authors are making reference to their previously published work – their older articles.

The papers are citing themselves, not previous work. NB you have left two comments that make the same error.

Presumably the pagination and volume # can be added at the page proof stage. But, it never occurred to me that anyone would try this stunt.

I had a quick look at the papers references for “database error” and I found that 2/3 papers don’t cite themselves but do cite a paper in the same issue. The other one seems to cite a previous manuscript in the same issue but then randomly adds in their current manuscript page just on the end. Hanlon’s razor springs to mind here.

Self citations are not always a bad thing. If you are extending your previous work or generalizing the older concepts you works upon, then you need to cite it. Whenever I had to cite myself in such cases, I always felt bad but I had no option as readers need to have previous published work of mine to make sense of new work. The solution could be that at whatever places citations is given important, they should simply calculate it by substracting self citations from it.

Citing papers in the same issue doesn’t seem too problematic now that most papers are available online for so long before they’re assigned to an issue. Special issues in particular can have articles piling up for a year or more.

sorry, but we have demonstrated that self-citations can be signatures of field mobility by researchers; when touching upon subjects which are not too well known by a scientist, he/she cites some of his/her work in order to justify some interest and in order to claim some competence; see, e.g., M. Ausloos, R. Lambiotte, A. Scharnhorst, I. Hellsten, Andrzej P{\c{e}}kalski networks of scientific interests with internal degrees of freedom through self-citation analysis, International Journal of Modern Physics C 19 (2008) 371-384, or I. Hellsten, R. Lambiotte, A. Scharnhorst, and M. Ausloos, Self-citations, co-authorships and keywords: A new method for detecting scientists’ field mobility?, Scientometrics 72 (2007) 469-486. and I. Hellsten, R. Lambiotte, A. Scharnhorst, M. Ausloos, Self-citations networks as traces of scientific careers. In “Proceedings of the ISSI 2007, 11th International Conference of the Intern. Society for Scientometrics and Informetrics, CSIC, Madrid, Spain, June 25-27, 2007”. Ed. by D. Torres-Salinas \& H. Moed, Vol. 1, 361-367 (2007).

…oops, self-citations!

Every paper I’ve written builds upon my previous work in some way. It’s hard to imagine a situation where someone would have publishable results that didn’t. I don’t understand the apparent confusion in this article – of course authors routinely reference their earlier work. How else would you situate the new paper in the existing literature?

The post and preprint refer to “paper self-citations.” The papers are citing themselves, not previous work. NB you have left two comments that make the same error.

I am astonished that the number of self-citations is so low. When I used to write a paper (my active period was in the last century), it was current practice not to repeat experimental details but to refer to a former publication.

Christian Steffen

As noted elsewhere in this thread, the study was only of paper self-citations — papers which cited themselves — not overall self-citations.

I think for non native speakers the article is a big vague. One could have reworded it a bit to make it more obvious. I was also confused first, thinking it was just about self citations but it’s about using the paper you ‘are writing’ as a reference itself which is quite astonishing.

I do not really understand this self-citation debate.

Granted: if you cite tens of your own papers, it might be a little questionable. But otherwise it is not really about “gaming the system” (and which system; we shouldn’t judge science by citations anyways…).

It is because science is really in most cases (cite Kuhn here) incremental.

And what gives about citations to background materials? Now that we finally have data repositories with DOIs, we should put everything to these and, doh, cite these!

Perhaps read the article first. Or just the comments, where your question is answered at least twice.

Unfortunately the authors of this interesting study cannot share their dataset because of legal restrictions in the usage of Web of Science data. Although it would be interesting to look more closely at the dataset to see if this phenomenon really exist. The authors gave some examples in the study, but as far as I see non of these qualify as real paper self citations: there is always some other explanation. Most probably the majority of the 44000+ cases are just artefacts caused by errors in the reference/citation matching algorithms in Web of Science.

Did the authors review each and every one of the 44,000 papers to see if each one actually managed to cite itself?

As far as I understand it from the text of the preprint the authors only checked some examples. Although they wrote the following in the dataset and methods section: “In total, we obtained 44,857 papers that have self-citation relations in the WoS raw dataset. In order to check whether these self-citations are merely database artefacts or if they really do exist in the scientific literature, we verified the self-citation relations in the WoS web-interface and checked them in the publisher’s PDFs.” But I doubt that they checked all 44857 papers in PDF, it would be a tremendous job, and such results are not presented in the preprint.

There is one example given by the authors which looks a bit like a real paper self citation: “Hicks, 1997” (https://doi.org/10.1071/p97006). Although I checked it and it is most likely some kind of typo: there are two articles in the same issue by the same author: one at page 1119 and one at page 1127. As I see the article at page 1119 tried to cite the other one at page 1127, but in the references page 1119 is given, probably becuase of an editorial/author error. Here is the table of contents for this issue: https://www.publish.csiro.au/PH/issue/152/. Both articles are freely available.

Ironically, the authors include their examples for paper self-citations in the reference list of their own study. With this behavior they might cause some interesting citation phenomena themself: they cite articles without a real reason to cite them, like those which look like paper self-citations because of database errors in Web of Science. There is no reason to include these in the reference list. Citation indices (like Google Scholar) already picking up these references from the prepint: https://scholar.google.com/scholar?as_ylo=2025&hl=en&as_sdt=2005&sciodt=0,5&cites=3999607131583453622&scipsc=

They should have listed the references in a table or in an appendix, and formatted them in a way that would not be picked up as citations! For example, a table with separate columns for author, date, article title, journal name, volume, and pagination. Leave out the DOI or other hyperlinks.