Philip G. Zimbardo passed away in October 2024 at age 91. He enjoyed an illustrious career at Stanford University, where he taught for 50 years. He accrued a long list of accolades, but his singular and enduring contribution to scholarship was the Stanford Prison Experiment, a simulation carried out in the university’s psychology department in August 1971. The research project became the best-known psychological analysis of institutionalization at the time.

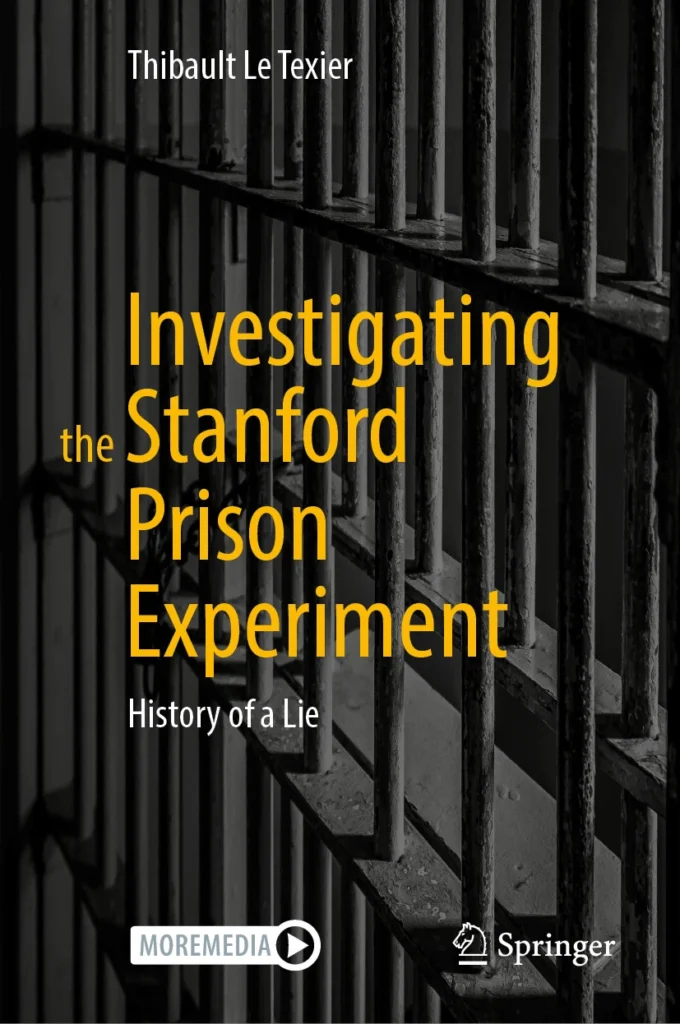

The study has always been treated with skepticism by penologists and psychologists, and recent scholarship by social scientist Thibault Le Texier has raised fundamental questions about the scientific validity of the investigation, the originality of the research design, the unethical treatment of the subjects, and the credibility of the reported results.

Many consider Zimbardo’s SPE to be one of the classic studies of experimental psychology in the post-war period. It continues to be reported as a landmark achievement in many psychological textbooks today, despite drawing decades of criticism both in and out of the scientific literature. But considering Le Texier’s findings, should Zimbardo’s work be retracted?

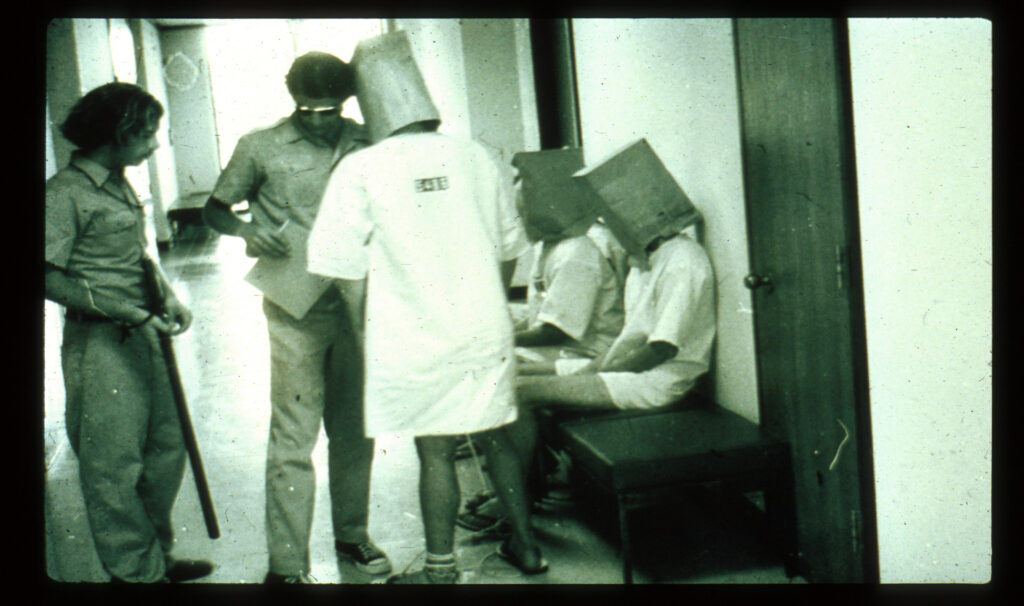

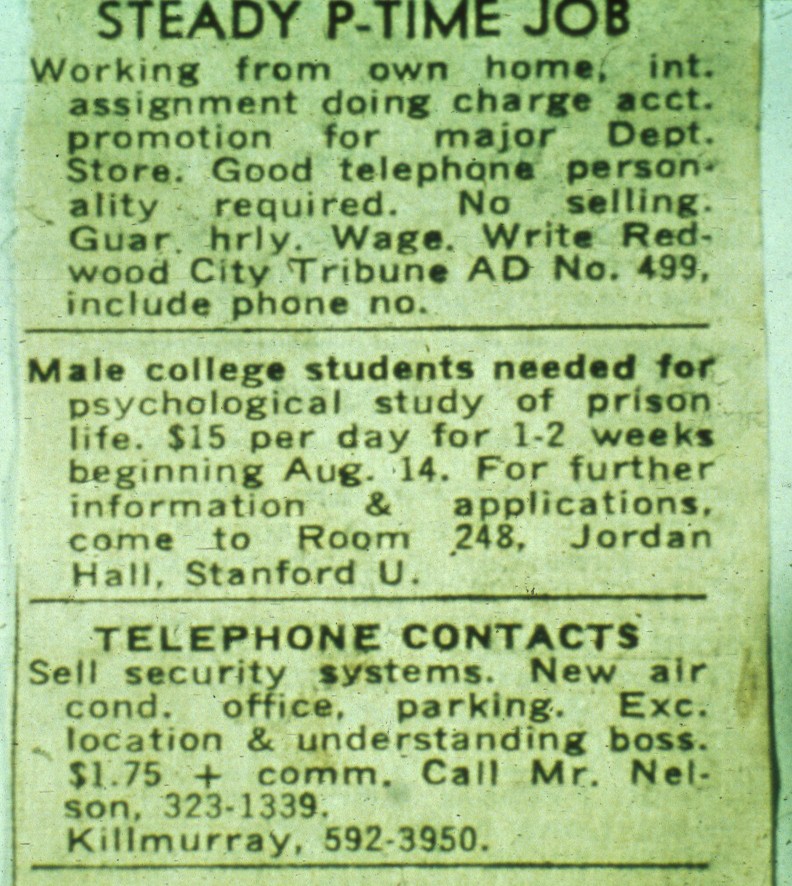

For the prison simulation, Zimbardo recruited 24 college-aged men and randomly assigned half to the role of guards and half to the role of inmates. “Inmates” were housed in mock “cells” in the basement of the psychology department, and “guards” worked three at a time over three eight-hour shifts. Everyone was paid $15 per day. A camera was installed surreptitiously in the main hallway of the “prison” to film the interactions.

The inmates were picked up at their homes by a member of the Palo Alto Police, “charged” with a serious felony and driven blindfolded to the mock prison, where they traded their clothing for a prison gown that included an identification number on the chest and back. The inmates wore nylon stockings on their heads to symbolize being shaved. Zimbardo played the role of prison director, a senior undergraduate student played the role of warden, and two doctoral students were cast as psychological counselors.

Participants began to exhibit pathological behaviors almost immediately. According to the videotapes, the guards showed signs of dominance and brutality, and the inmates exhibited signs of depression and defiance.

This interpretation was based on the proposition that the primary determinants of social behavior are situational: Personal autonomy was assumed to be overshadowed by situational roles. What started as mocking antagonism — play-acting — degenerated into degradation and abuse on the one side, and depression and rebellion on the other. According to the conventional interpretation, an experimental simulation increasingly came to approximate the real thing.

In 2014 Le Texier started researching the SPE, initially planning to make a documentary film for French media. He delved into the archives of the experiment, including the documents, videos, and interviews Zimbardo had cataloged and archived in the Stanford Library. Le Texier later interviewed about half of the original participants by phone to reconstruct what happened.

He realized how flawed the conventional interpretation was, and ended up writing a book on it, originally published in French in 2018 and translated into English in 2024. “My enthusiasm gave way to skepticism, then my skepticism to indignation, as I discovered the underside of the experiment and the evidence of its manipulation,” Le Texier wrote in the introduction of Investigating the Stanford Prison Experiment: History of a Lie.

Four main themes come to light in Le Texier’s book that undermine the credibility of the SPE.

1. The scientific credentials of the study

As Le Texier points out, Zimbardo had no expertise in criminology. His doctoral training was behavioristic and his subjects were lab rats. His interests at Stanford changed to questions of deindividuation of people in mass society. Consequently, the SPE began as a kind of observational study, not of a real prison but a drama enacted by subjects pretending to be guards and inmates.

On the Saturday before the experiment started, the guards were briefed about how they were expected to behave. The message: essentially to make the lives of the inmates miserable. Zimbardo equipped them with riot batons borrowed from the Palo Alto police department, without training the recruits to use the weapons.

In the following days, several guards were reprimanded by the experimenter’s assistant for not displaying sufficient dominance to make the situation realistic. The apparent spontaneity of the pathological behavior captured on film was due in part to coaching. On Monday, their first full day together, the inmates planned a prison break to defy authority. This action suggests the subjects also drew from their own background knowledge of prison experience portrayed in popular media.

Le Texier argues the SPE was not a scientific experiment at all, but a demonstration created to depict the evils of incarceration based on the supposition that institutions can make normal people act in pathological ways. Although Zimbardo’s results were not reported in peer-reviewed journals until 1973, he communicated his “findings” by press release at the end of Monday, the first full day of the experiment. The experiment started to attract press coverage by the following Thursday.

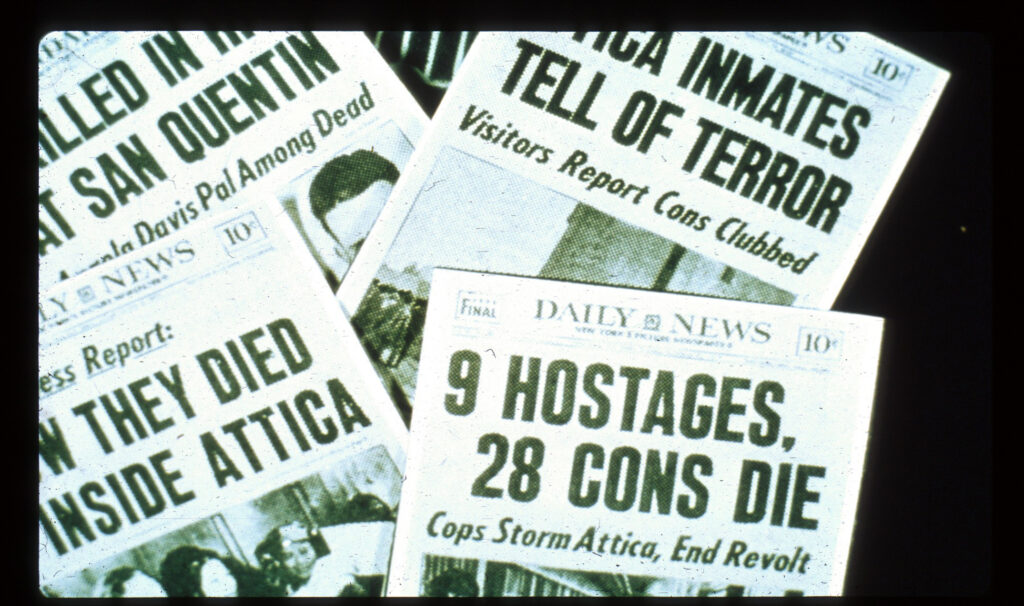

A bloody attempted prison break at San Quentin State Prison the day after the experiment ended was followed within weeks by a major prison riot at Attica Correctional Facility. In the shadow of these events, Zimbardo’s findings skyrocketed to national prominence as the SPE was invoked as context to this violence. Within a month, Zimbardo found himself speaking as an expert to a congressional subcommittee on criminal justice policies.

The SPE became a cause célèbre before it underwent peer review. Interest in the findings revived in 2004 following reports of inmate abuse at the Abu Ghraib prison. According to Le Texier, despite the publicity it attracted, the SPE was never a credible scientific experiment. The research lacked a defined theory and a priori hypotheses, did not use any validated sociometric instruments to measure behavioral differences, had no tests of significance, and did not include a control group.

2. The originality of the SPE design

The official history of the SPE is recorded in a large slideshow, which Le Texier employed as one of the main sources for his research. Zimbardo also produced a 19-minute video for circulation.

One of the items Le Texier discovered in the archive was a term paper by David Jaffe, a senior undergraduate in a seminar Zimbardo offered in the spring of 1971 – several months before the launch of the SPE. Jaffe and two classmates had created a prison simulation in their dormitory at Toyon Hall as a course assignment. They scripted a typical daily schedule for the inmates as well as a list of prison rules. The objective of the simulation was to mimic the effects of real prison by trying to create feelings in the “prisoners” of the loss of freedom, total dependency on the guards and feelings of worthlessness.

In his various reports Zimbardo insists the routines and rules in the SPE were improvised spontaneously by the guards. However, when Le Texier compared the rules and schedules in Jaffe’s term paper with those allegedly concocted by the SPE guards, he found them to be virtually identical. Jaffe was also employed in the SPE as the “head guard.” However, his role in designing Zimbardo’s experiment is rarely credited.

“Instead of acknowledging the foundational importance of the Toyon Hall experiment, Zimbardo completely obscured it for 40 years,” Le Texier wrote. “He does not mention it in the slideshow he used for 20 years to present the experiment, nor in the documentary Quiet Rage that succeeded it in 1992.”

3. Ethical Issues in the treatment of subjects

In the protocol submitted to the Stanford Human Subjects Research Review Committee, Zimbardo indicated subjects would only be released prematurely for “emergency reasons” and would be “discouraged from quitting.” However, the committee appears to have mandated that if anyone wanted to quit, “they would be released; no explanation needed.” In fact, the experimenters did not release inmates when several individuals expressed a desire to quit. They were told voluntary departure was not an option and they would have to apply to the parole board. Consequently, the loss of freedom was not simulated.

The loss of privacy was not simulated either. The prison gown was worn without underwear, so when the guards forced inmates to play “leapfrog” their genitals were exposed. The inmates were denied access to showers and deprived of access to the toilets at night and had to use a bucket as a commode in their cells.

Questionable treatment raises ethical issues as well. Guards interrupted inmates’ sleep with blasting whistles, and called the inmates out of their rooms for meaningless head counts in the middle of the night. They handcuffed and blindfolded inmates to march them to the toilets. When a guard assaulted rebellious inmates by spraying them with a fire extinguisher, or struck them with a riot baton, neither act was simulated.

In the search for verisimilitude in a role-playing environment, Zimbardo exposed his subjects to a series of ethically dubious conditions and was reckless in his gamble that no one would get seriously offended, injured or sick.

4. The credibility of the results

The six days of interaction between the inmates, the guards and the experimenters created emotionally provocative moments even if the participants knew, at least initially, the “prison” was a pretense, everyone was more or less acting, and they were being paid as subjects in an experiment. As Le Texier reported: “His experiment had effects on all of its participants, inducing stress, tension, aggression, indifference, resignation, or even apathy.” By analogy, audiences sometimes weep at the theater even when they know the play is fiction. But to what extent were the significant changes observed by Zimbardo cases of deliberate play acting?

Zimbardo reported five inmates experienced “nervous breakdowns” over six days and were released. However, post hoc debriefings suggest at least one of these subjects said he faked emotional trauma by screaming, crying, threatening suicide and acting out physically to trigger a “medical emergency” — after being told he could not leave. According to Le Texier, what that suggests is that “Zimbardo strongly encouraged the prisoners who wanted to leave the experiment to simulate a nervous breakdown.”

On the guards’ side, one of the subjects who adopted a tough guard persona and was most aggressive toward the inmates adopted a fake Texas accent and admitted his facade was an act played for the camera. In fact, he was a drama major.

Should the SPE be retracted?

At some point, when the credibility of a classic study has received so much critique, official retraction, while desirable, becomes redundant. What Le Texier added to the record is not only the dubious value of Zimbardo’s findings but his virtually unacknowledged appropriation of the ideas of his students and his exploitation of mass media to promote his ideas in advance of peer review. If we were seriously talking about retracting the SPE, what exactly would be retracted?

The first refereed paper, “Interpersonal dynamics in a simulated prison,” appeared in the International Journal of Criminology and Penology in 1973. By that time, the popular press had papered the walls with the news of the study. Le Texier identified a dozen newspaper reports in the weeks following its termination including Life, The Daily Mail and The Washington Post.

The SPE provided context in news reports of the lethal breakout at San Quentin the day after the experiment ended and the bloodbath following the riot at Attica three weeks later. Another wave of newspaper stories in October and November covered Zimbardo’s congressional testimony. In 1972 Zimbardo submitted a short report to Society, a popular sociology magazine, called “Pathology of imprisonment.” And recounted the experiment in The New York Times Magazine in April 1973 in “The mind is a formidable jailer: a Pirandellian prison.”

By the time the study was reported in the International Journal of Criminology and Penology, it was common knowledge. The IJCP ended publication in 1978. It was superseded by the International Journal of the Sociology of Law (1979-2007) which was itself superseded by the International Journal of Law, Crime and Justice. Consequently, a retraction in the IJCP is not even possible. If Le Texier’s findings are credible, arguably the best outcome we can expect is more responsible reporting in contemporary textbooks.

Like Retraction Watch? You can make a tax-deductible contribution to support our work, follow us on X or Bluesky, like us on Facebook, follow us on LinkedIn, add us to your RSS reader, or subscribe to our daily digest. If you find a retraction that’s not in our database, you can let us know here. For comments or feedback, email us at [email protected].

Maybe the best conclusion is that in the search for publications and media exposure, academics can be unethical. One problem with retraction of papers this old, is that they probably met the publication standards of the time. All sorts of rubbish used to be published, far more than today. Lots of nonrandomised studies.

That’s probably true- you could publish about this stuff. But, ethically speaking, it’s not like conversations weren’t happening about participation being voluntary, particularly after World War 2 and the establishment of the Nuremburg Code. Ethical research also produces good data – the results of these studies are biased because it was not ethically conducted. I think the paper should be retracted because it takes so much time for things like this to be debunked thoroughly. I’m sure this study is still in psych textbooks and I’d like to know that a budding psych student could look up the original study and know that it isn’t reliable.

No. Zimbardo probablemente estuvo en los límites de la ética y el diseño, pero logró avances en el tema de Salud Mental en situaciones como las de confinamiento en prisión. Tal vez deberíamos pensar también en hacer retractación de otros experimentos en los que se abusó de animales y humanos y en ese caso la Psicología resultaría muy afectada. Hay un proceso histórico en investigación que hace medio siglo no estaba totalmente definido pero que cumple con la teoría de ensayo y error.

No. Standards, of ethics, of experimental design, of experimental practice, of reporting improve (or at least should improve) all the time. It’s hardly a surprise when we find a historical experiment has even the most enormous flaws.

We learn by looking at how badly things were done in the past. We need to accept that science isn’t a wall where we put solid bricks on the solid bricks others have placed in the past. It’s a wobbly thing where our bricks are better than those they stand on, but periodically we find the foundations were no good, and a chunk of wall falls down, and needs major alterations.

“Retraction” is too black-and white to deal with most historical failings. Big historical papers should generate commentary and follow-up; they become the start of a story. The whole story should be in the public domain, even if the original paper gets totally debunked. This way, everyone can see not only that it’s debunked, but why, and how not to do it again. The process of debunking is as important (or more important) than the mere fact it’s debunked. So we can’t debunk-and-move-on.

Classic retractions aren’t peer-reviewed, they aren’t ascribed to a particular author, they’re just a statement, from an editor, that something is not to be believed. Historical mess-ups need explanation, interpretation, and investigation, authorship and traceability. They need to be published, not to be handled by retraction. Le Texier has, correctly, published his contribution to the story. What can retraction add? It won’t punish Zimbardo. It won’t deter bad science; in fact the more Zimbardo’s experiment and Le Texier’s investigation are discussed, the more chance there is of younger scientists deciding how to plan, interpret and evaluate experiments better.

Mendel’s work is a concrete example. His experiments were called into question in the 1930’s by Ronald Fisher, one of the world’s most heavyweight statisticians, who said the data were too good to be true – a classic PubPeer accusation of statistical fraud that in a modern paper would lead to retraction. Fisher’s own investigation has since been called into question, and it now looks like Mendel might have been okay all along (Hereditas 156, article 33, 2019). If we’d retracted Mendel’s papers in the 1930’s because of Fisher’s accusations, would we now be un-retracting them? Would we be retracting Fisher’s (honest) investigation? How do you retract a retraction anyway? History matters: we keep these old bits of work, faults-and-all, but we add to their story, so it can be seen accurately for what it means (or doesn’t). Labelling it “retracted”, or hiding it, is very unhelpful.

Great points. BTW see my old article on “The Reification of Mendel,” Soc Stud Sci 1979. Fisher said Mendel’s 3:1 ratio was better than expected in an ordinary field trial. That’s not quite proof of fraud, especially since the experiments could be replicated.

Prof Zimbardo did respond to some of Le Texier’s concerns, but not the most cogent criticisms.

I am impressed you took the care to offer a more moderate perspective on the choices regarding retraction.

Hi Li,

Thanks for your very insightful input. The Mendel example is superb – one which I knew little about until your post.

Re https://retractionwatch.com/2025/03/10/guest-post-should-zimbardos-stanford-prison-experiment-be-retracted/

How about the Milgram experiment ?

https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Milgram_experiment

How weird is it that Milgram and Zimbardo went to high school together?

In simple terms this “experiment” took students from the university and told them who would be prisoners and who would be guards.

So there were massive biases before starting up – i.e. believing people would “act” out their roles without questioning.

For example: when a prisoner gets agressed by a guard, then that person might chuck out all the acting and demand a stop. Retaliate as one student versus another etc – “you’re not really a guard…”

Today this would be a Reality TV show.

The real problem is media, politicians and idiots doing their interpretations to fit their biases.

One of the fundamental problems with this experiment wasn’t even mentioned. TLP talks about it, though:

https://thelastpsychiatrist.com/2009/11/stanford_prison_experiment_red.html

“male college students needed for a psychological study of prison life. $15/day for 1-2 weeks

It’s a legitimate question: what kind of a nut signs up for that?

There’s an answer. In a follow up experiment in 2007 designed specifically to answer that question, two ads were placed in newspapers, one recruiting “male college students needed for a psychological study. $70/day for 1-2 weeks” and the other, slightly different ad recruiting for “a psychological study of prison life. $70/day for 1-2 weeks.”

The subjects weer screened with personality inventories, and, surprise, “prison study” recruits scored significantly higher on narcissism, social dominance, aggression, Machiavellianism and authoritarianism (but especially the first three.)

When you do a study, you get what you pay for.”

No. I don’t believe it should be retracted. It is a reminder and caution as to how quickly people can do things they ordinarily wouldn’t do under certain situations. I am reminded of Nazi Germany. Ordinary Germans became Nazis and killed people.

Did you even read the post you are commenting on? It wasn’t an experiment, it was a piece of political theater. You may have liked it, but it is on no way a scholarly contribution to the subject it purports to study. If anything, it is useful as a lesson on the gullibility of academics and others when presented with “evidence” supporting their beliefs.

It was an observational study, if it is discussed as such I don’t see a problem, such studies can never be fully controlled and free of participant behavioural preconditioning and excessivly trying to do so probably opens them to equal or even greater biases. Like much distant science that has become totemic it has been lifted out of and stripped of it’s contemporary context and it is a very good thing that someone has gone to the effort of looking at it in proper detail and gone back to the source material.

You may call it an “observational study” if you like, but it wasn’t an experiment. Furthermore, the behavior “observed” was so tainted that the observations are meaningless. I think it is more accurate to describe it as political theater, and the observations have no value to science or even psychology.

It was was a short term small scale observational exercise, because of its timing and those of external events it bacame more prominent than it deserved. However it was systematically observed and recorded which lifts it beyond experemental theatre or a perfomance art exercise. Flawed and most certainly unethical by even contemporary best practice, but worthy of discussion and if cogniscent of it’s details some interpretation.

How does its being “systematically observed and recorded” lift it beyond theater? Leaving aside the ethical issues that seem to fascinate everyone, it is simply scientifically worthless.

There’s a bigger methodological hole that never seems to get mentioned, and it bugs me mightily. I got to have lunch with Zimbardo and then hear him speak in 1995 or 1996. I asked him more details about how the study was begun. The students were instructed “I want you to act exactly as you think an prison inmate and a prison guard would behave.” So. This is the early 70’s, in Stanford California, during the Viet Nam war. These are MASSIVE examples of what Campbell and Stanley (Experimental Design) called historical threats to external validity. Guess what undergrad kids at Stanford though of police? You don’t have to, because Zimbardo simply documented what Stanford undergrads thought of police in his study. Furthermore, as Milgram demonstrated, both undergrads and adults will absolutely follow instructions of an authoritative figure supervising their behavior. The Stanford Prison Experiment is just silly. Not an academic masterwork. Not at all a good example of psychological experimental design. A GREAT case study for how to screw up an experiment and get the results you want.

It is literally too late for retraction but that doesn’t mean it should be expunged from history. I have used Zimardo’s work along with Marc Prensky’s article on digital natives and Milton Friedman’s article on the social responsibility to teach undergraduate commerce students about logical fallacies.

I was always pleasantly surprised with my student’s critiques of these works when armed with only a short introduction to the ways in which arguments can be wrong.

It is better to keep the flawed works available so that young people can learn to distinguish between a good argument and a flawed one.

A journal being renamed doesn’t remove its responsibility for the content it has published. An Expression of Concern or Editorial that highlights the ethical and methodological problems would be appropriate, in my opinion.

I’d be willing to guess that the participation demographic, chosen from the Stanford student body circa 1971 was not exactly a slice-of-life reflection of American demographics as a whole (at that time, or since). What sort of default settings did the men involved possess, simply thanks to the sort of background that led one to a highly selective and well-endowed university at that time and in that place?