A psychology journal has retracted an article on IQ tests nearly 50 years after publication — and more than 35 years after an investigation found the lead author had fabricated data in several other studies.

Stephen Breuning, a former assistant professor of child psychiatry at the University of Pittsburgh, gained notoriety after a 1987 National Institute of Mental Health report found that he “knowingly, willfully, and repeatedly engaged in misleading and deceptive practices in reporting results of research.” The report concluded Breuning had “engaged in serious scientific misconduct” by fabricating results in 10 articles funded by NIMH grants.

Five of Breuning’s articles published in the 1980s have been retracted; three in the 1980s, one in 2022, and another in 2023. Retraction Watch reported on one of them, “Effects of methylphenidate on the fixed-ratio performance of mentally retarded children,” published in 1983 in Pharmacology Biochemistry and Behavior (now published by Elsevier) and retracted in 2022.

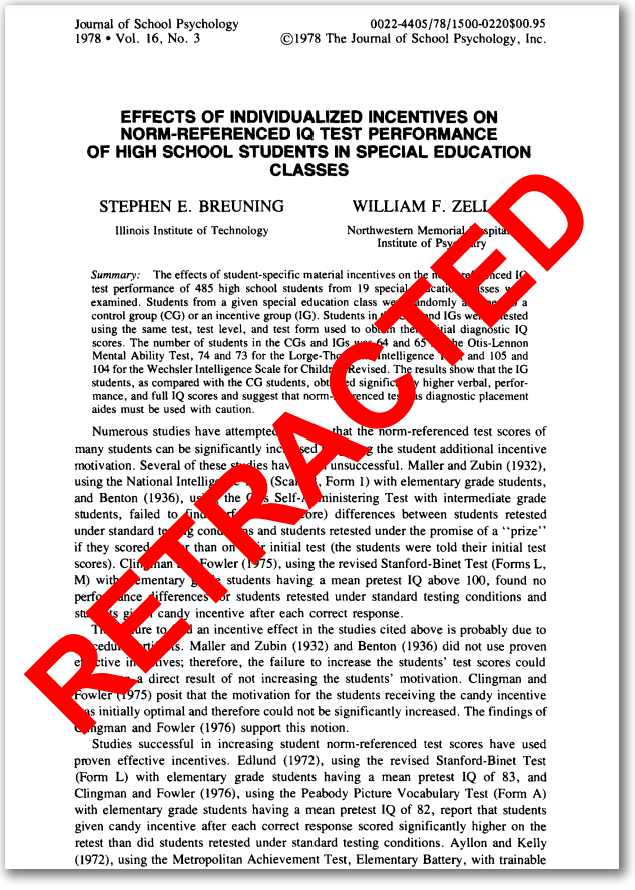

The newly retracted article predates those papers. Published in 1978 in the Journal of School Psychology, “Effects of individualized incentives on norm-referenced IQ test performance of high school students in special education classes,” found record albums, sporting event tickets, portable radios, and other incentives boosted scores on IQ tests.

To many, including research psychologist Russell Warne, who has been investigating Breuning’s work since late 2021, these seemingly simple results appeared “too good to be true.” In early 2022, Warne emailed the journal’s editor-in-chief Craig Albers, raising concerns about the article’s validity.

Now, nearly three years later, the journal, an Elsevier title, has retracted the study.

The retraction notice, issued in December 2024, acknowledged the NIMH investigation, and continued:

“Within this Journal of School Psychology article, the research was reported to have been conducted in seven suburban Chicago high schools across four school districts. Although the above article was not part of the NIMH investigation as it fell outside the scope of NIMH funded research, the NIMH Panel report identified an ongoing pattern of scientific misconduct by Dr. Breuning that introduces substantial concerns regarding the trustworthiness of this article. Despite several attempts, Dr. Breuning has not responded to requests for an explanation. The co-author confirmed that he (the co-author) was only involved in statistical analysis and not in data collection. This article has been retracted at the request of the Editor-in-Chief due to concerns about the integrity of the data reported and other issues identified within the NIMH Final Report that clearly established a pattern of ongoing scientific misconduct.”

When we reached out to Albers for comment, an Elsevier spokesperson responded with a statement that reiterated the retraction notice. We followed up to ask why it took several years to issue the retraction, and they said via email, “The journal team took all necessary steps during the investigation, including notifying the author, which can often cause delays before the final decision is made.”

Warne said he believes several factors contributed to the delay, including Albers’s recent appointment as editor and his initial email being mistakenly sent to the wrong folder. “I don’t know why it takes so long, and I really wish the COPE ethics guidelines would put recommended deadlines,” Warne said.

In January and February 2022, Warne published blog posts outlining Breuning’s unretracted and potentially fraudulent work, including studies that weren’t part of NIMH’s 1980s investigation because they had different funding sources. This research led him to Breuning’s 1978 article.

Among several concerns, the most striking to Warne was the rapid speed and scale of the experiments, as well as the results showing significant IQ score increases with such simple incentives. He said, “If it were that easy to raise IQ, I think we would know that by now.”

While gathering evidence, Warne also spoke with the study’s co-author, William Zella. Breuning and Zella were in graduate school at the Illinois Institute of Technology in the 1970s, and Zella told Warne that Breuning had enlisted him as a coauthor to analyze the data and assist with the write-up.

When Warne spoke with him, Zella “agreed that the study probably never happened.” More than four decades had passed since the study was conducted, so understandably, Zella could not recall many details. “He was not pleased that his co-author classmate from graduate school decades before had done this and that his name was attached to it,” Warne said. Zella clarified that he had no involvement in administering the tests or coordinating the volunteers.

In the 1980s, Breuning made major headlines, but since then, his name has largely faded away. A 1990 study by Eugene Garfield and Alfred Welljams-Dorof found Breuning’s work was largely rejected by the academic community. While Breuning’s research was cited often, few articles were in agreement with his methods or findings.

But his unretracted work remains in the scientific record and is still cited in meta-analyses and other studies. Breuning and Zella’s 1978 article has been cited 12 times, according to Clarviate’s Web of Science. And a 2011 meta-analysis in PNAS, “Role of test motivation in intelligence testing,” includes data from the paper and has been cited more than 200 times. Breuning’s work significantly influenced the results of that meta-analysis, Warne said.

Warne said he has reached out to the lead author, Angela Lee Duckworth, and to PNAS, and was informed by the publisher that the journal is investigating the matter. When Retraction Watch reached out to PNAS for comment, Prashant Nair from the news office responded via email with the same sentiment: “We are aware of the matter and looking into it.”

Warne believes the journal should first publish an expression of concern to clarify that Duckworth and her co-authors are not at fault.

Warne sees Duckworth and her collaborators, as well as Breuning’s coauthor Zella, as victims of Breuning’s fraud. One of Warne’s primary objectives in all of this is to highlight how long-buried fraudulent articles can continue to cause harm and “re-victimize people.”

Like Retraction Watch? You can make a tax-deductible contribution to support our work, follow us on X or Bluesky, like us on Facebook, follow us on LinkedIn, add us to your RSS reader, or subscribe to our daily digest. If you find a retraction that’s not in our database, you can let us know here. For comments or feedback, email us at [email protected].