An education researcher who had four papers flagged for plagiarism and citation issues threatened to sue the publisher and editors who decided to retract one of the articles, Retraction Watch has learned.

We obtained the emails containing legal threats by Constance Iloh, formerly an assistant professor at the University of California, Irvine, through a public records request. Iloh, who was named to Forbes’ “30 Under 30” top figures in education in 2016 and briefly taught at Azusa Pacific University after leaving Irvine, sued to prevent the university from giving us the emails, but after a two-year legal battle, a state appeals court affirmed the records should be released. That battle is described in more detail in this post.

Following our reporting in August 2020 on the retraction of one of Iloh’s articles for plagiarism, the disappearance of another, and the correction of two more, we requested post-publication correspondence between UCI, Iloh, and the journals where the papers had appeared.

The emails UCI released to us in May of this year shed light on the processes three journals took after concerns were raised about Iloh’s work, and how she responded.

The documents do not indicate UCI had any formal involvement in correcting the scholarly record. Whether the university opened an investigation into allegations of research misconduct is unclear; they told us they were “not in possession of responsive releasable documents” when we requested reports of such an inquiry.

Iloh and her lawyer, Elvin Tabah, have not responded to our request for comment. In a Medium post, Iloh claimed she experienced “academic mobbing and bullying” at UCI, actions that include “attack, harassment, humiliation, trolling, stalking, death threats, doxxing, and even online identity impersonation.” She described anonymous complaints asking the university to investigate her work for plagiarism as “a hit job” and called coverage of the actions journals took with her papers – presumably our posts – “deviant clickbait.”

In response to our previous emails to Iloh offering her an opportunity to comment, another UCI faculty member sent us legal threats, which the university said “were personal and not made on behalf of the University.”

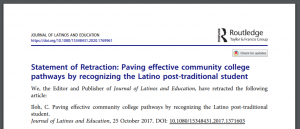

Iloh’s emails with staff at Taylor & Francis, which in 2017 published her article “Paving effective community college pathways by recognizing the Latino post-traditional student,” in the Journal of Latinos and Education, reveal that two years elapsed between the publisher opening an investigation into the article and publishing a retraction notice.

In January 2019, a production editor at Taylor & Francis sent Iloh a PDF copy of her manuscript for her to mark up or submit a list of changes. Iloh replied with an updated manuscript on March 1.

On May 3, the managing editor of the Routledge US Education Journals informed Iloh the publisher had received “feedback [that] inquires about the originality of some sections of text” of her article. The editor offered her “the opportunity to provide clarification on the text in question,” specifically “the decision of the specific material cited (primary versus secondary sources) and the use of direct reproduction of text from sources.”

Iloh responded a few days later. She asked for the “original feedback” to give to her lawyers and said she was not sure what the managing editor was asking of her. “It seems as though you have already made a judgment with ‘decisions’ so I am just not sure specifically what you are asking me to do.”

In the ensuing exchange, the editor gave Iloh multiple opportunities to comment on particular parts of her article and explain “the specific texts used and/or referenced within your article where there is a high degree of similarity.”

Iloh made veiled legal threats at multiple points, claiming the article didn’t go through copy-editing before publication and she had tried to correct it. She wrote:

I have reached out to the journal with edits that I was told would be done and instead, I was accused of making “decisions” on an article the journal acknowledged having published without copy-edits and me ever completing them.

It was also made clear to me “someone” was clearly “out to get” me, so I already have working understanding this matter is more than what is described.

The managing editor’s response gave Iloh a deadline of October 18 to comment on the “textual overlap that was brought to our attention.”

In the next email in the records, dated March 12, 2020, the managing editor informed Iloh of the publisher’s decision to retract the paper due to “significant textual overlap between your article and several other works.” She gave Iloh a week to respond.

Iloh’s responses repeated her claims that the article had not been copy-edited and she should be able to correct the article with added quotation marks and references. She again threatened legal action against the publisher and the whistleblower:

I wish to reiterate legal recourse in event of aforementioned direction from your prior correspondence. I would also like a copy of the original accusation from the “anonymous” so that they and those colluding with them are accordingly dealt with in legal proceedings.

The managing editor replied to Iloh the next week with documentation that the article had indeed been copy-edited and Iloh had made corrections in the process before publication. She explained that the publisher had opened an investigation on Nov. 1, 2018 into “textual similarities in your article we had been alerted to.” She also explained the publisher’s process of reviewing requests to change articles after publication, and that they do not make changes while investigating an article.

Over the next few months, Iloh and the managing editor exchanged more emails in which Iloh repeatedly threatened legal action and called the decision to retract her article “problematic and unlawful.” The managing editor reiterated Taylor & Francis’ decision and policies, including that the changes Iloh had requested “are too extensive for us to publish as a correction notice.”

The retraction notice was published on August 10, and we posted our first story on Iloh later that month.

In subsequent emails, including one sent to Taylor & Francis executives with further threats to sue the company, Iloh accused the journal’s editors of “bias.” She also cited an error in the original retraction notice and claimed that journal staff were “determined to cause harm to me and retract my article, even on faulty grounds.”

Taylor & Francis corrected the retraction notice, which said her 2017 article had “text overlap” with an article she had published in 2019, but otherwise stood by its processes and decision to retract the article in a letter from Jessica Vivian, the global portfolio director in charge of education journals.

Vivian’s letter reviewed the publisher’s documentation that the article had been copy-edited, contrary to Iloh’s claims, and the process they had taken to retract the article and give Iloh an opportunity to explain the textual overlap, which she did not do. The letter also reiterated the company’s plagiarism policy and assessment that “the amount of textual overlap was far too substantial to warrant addressing the textual overlap through a correction.”

“With regards to your allegations of abuse and mishandling of your case,” Vivian wrote, “I would welcome the opportunity to review evidence against this claim. If you have this, please do share that with me at your earliest convenience.”

Vivian sent the letter on September 8, the day we filed our records request, so it is the last document included in the records UCI released to us. We do not know how Iloh may have responded.

The publisher’s investigation “was conducted properly and professionally and we stand by the conclusions of the re-review of this case,” Mark Robinson, corporate media relations manager for Taylor & Francis, told us in an email. “There was a careful investigation into concerns about the article and extensive correspondence with the author, which is why the process took some time.”

In other correspondence we obtained, Iloh and staff at the publisher Sage took six months to agree on and publish the wording of a correction notice. Iloh objected to language indicating the original article had problems that were being fixed; staff described the changes she wanted to make to proposed wording as “not transparent enough.”

The article at issue, “Does distance education go the distance for adult learners? Evidence from a qualitative study at an American community college,” appeared in the Journal of Adult and Continuing Education in 2018. The emails we obtained start in January 2019 with Iloh apparently sending an updated version of the article attached to an email with no body text.

In another email to the journal’s editor and a Sage employee who managed the journal, dated March 21, Iloh seemingly sent an attachment related to the correction, but the email’s subject is blank and the body text does not specify what she attached.

The managing editor’s reply on March 27 thanked Iloh for “reviewing the draft corrigendum,” but continued:

However, we have concerns about the changes which you have made, particularly removing the record of references which have been amended/included in the updated version of your article.

The editor explained Sage’s policies “in line with best practices of transparency when making changes to a published version of record.”

The early version of the corrigendum stated:

The author regrets that at the time of submission the following sources were not adequately referenced

Iloh responded:

I hope this email finds you well. Per my previous email, this is not accurate however. Those references were not left out, they were added because of new text. I also do not approve of any language that includes “the author regrets.” I can send a new version as again I do not approve of the current and would never allow such. I will submit shortly.

After waiting for Iloh to send her updated version, the Sage editor sent a new revision with “only the information that it is essential to inform the readers of the changes to the version of record.” Iloh did not approve of it, either, and sent her proposed version on May 8.

By that time, the previous managing editor had left Sage, and a new staffer had taken on the role. The editor responded on May 15:

We have accommodated your changes as best we can, however the latest changes you have suggested are not transparent enough to meet the criteria set out in the COPE guidelines. We have the agreement of the Editor of the Journal of Adult and Continuing Education on the corrigendum wording, and will therefore be proceeding with the publication of the corrigendum text as attached with this email. I would like to thank you for your co-operation on this matter and hope you appreciate that SAGE and the Editor of the journal are responsible for ensuring transparency and that relevant procedures are adhered to, and therefore have full discretion regarding the content of the corrigendum wording.

Iloh sent another version the same day, writing:

As you can see, those references were added in updating the text but they were not missing in the one from before so I want accuracy as well.

The editors accepted Iloh’s revision.

After extensive emails in the proofing stage of production as Iloh questioned whether one reference was written correctly and asked to remove two references to her prior work (the article Taylor & Francis was in the process of retracting and another that would be removed), the correction was published in July 2019. It stated that “sections throughout the original manuscript have been re-written and updated and this manuscript also includes new references.”

We asked SAGE about the journal’s decision to publish Iloh’s correction to the article, which added eight references. A spokesperson said:

Those at Sage who were involved with the decision to publish a correction notice for the article are no longer at the company. Our current research integrity team is looking into what, if any, action we should take on the article now.

Iloh’s article “Not non-traditional, the new normal: adult learners and the role of student affairs in supporting older college students” appeared in the 2018 edition of the Journal of Student Affairs. The entire issue had been removed when we wrote our August 2020 post, without any notice. The emails we obtained shed light on what happened.

In March 2019, Iloh emailed Colorado State University’s Student Affairs in Higher Education program, which publishes the Journal of Student Affairs, with an updated version of her article. According to the researcher, the new text had “minor errors corrected” and two additional references. She wrote:

I did not know there wasn’t a copy editing stage, after receiving a revise and resubmit and then an acceptance. I wanted to make sure I took time to carefully correct any errors following my return from family tragedies.

In the next email in the records, sent in December 2019, a CSU professor informed Iloh that the school’s leadership had decided to remove her article from the 2018 issue of the journal after a “plagiarism check” indicated “significant cause for concern.” The professor attached the TurnItIn report, which revealed

direct use of others’ words, including whole sentences, without proper attribution. The most significant of which include the improper use of work by Chen (2017), Ke (2010), and Panacci (2015), as well as of your own work and a Concordia University website.

“I regret this situation keeps dogging you,” wrote the professor, who also mentioned talking with Iloh at an education conference.

Because Iloh had tried to make changes to the article after publication, the professor offered Iloh the opportunity to submit a revision “with the plagiarism issues noted in the reports corrected.” If Iloh submitted a new manuscript, the professor wrote, “we will scan it again and assuming all issues have been corrected, we will republish the article online with an errata note that it was originally published in 2018 and revised due to errors in attribution.”

If Iloh did not resubmit, the professor wrote:

JSA must then note in the journal archives that your article was pulled from the issue due to significant errors in attribution.

I regret that we must take this course of action, but the integrity of the journal and these students’ work as editors must be upheld.

Iloh submitted an updated version of the article the same day.

In March of 2020, the professor conveyed the journal’s decision that the new version didn’t sufficiently address the plagiarism issues, and the journal would not replace the article.

“Although the percentages of individual similar content is very small, I still find issues with inappropriate use of secondary sources appearing as primary sources,” the professor wrote. “Consequently, it is thought that the core issues found with the original manuscript, although reduced, are still evident due to not appropriately attributing secondary sources.”

Iloh replied later that day:

No worries, it is fine just being left it out. Thanks for your correspondence and I hope you are taking good care. I am not even sure what version I sent when I received your first email (as I was dealing with family deaths but wanted to respond given the nature), but these issues will never arise again. I apologize for any inconvenience.

We pointed out to the Journal of Student Affairs’ current leadership that at the time we were reporting this article, a PDF of the journal issue in which Iloh’s article appeared included the text as it originally appeared, with no notice. The professor now in charge of the journal thanked us for pointing out “an error in our website” and said the journal would take the issue down “until an original file can be located to edit and reupload.”

Like Retraction Watch? You can make a tax-deductible contribution to support our work, follow us on Twitter, like us on Facebook, add us to your RSS reader, or subscribe to our daily digest. If you find a retraction that’s not in our database, you can let us know here. For comments or feedback, email us at [email protected].

didn’t thoroughly go through the entire history of this case yet (probably won’t either), but upon first reading… boy you guys really went in on Constance Iloh for what seems to boil down to: a few dozen missing quotation marks, some ‘self-plagiarism’, and a couple of missing references

honestly it really does seem like you’re being complicit in someone’s ‘hit job’, either wittingly or unwittingly

and considering you’re asking for donations to recoup the $4.000 or so that you burned on obtaining all this correspondence and filing stuff, i urge readers to think twice about donating if you’re going to continue spending that kind of money on bullshit cases like this

“I didn’t get all the facts, and I won’t, but I need everyone here to know that I think plagiarism is ok if you only do it some published papers. Four is not too many. That’s a reasonable amount of plagiarism, and it’s also reasonable to refuse to remedy the plagiarism when provided with an opportunity to do so. Another thing that is reasonable: making actual legal threats requiring legal response at the people who are publicizing that you have plagiarized. Since that is all reasonable, any action against the plagiarist is a witch hunt.”

please cite the source of that quote before your comment gets retracted

Oh Sweetie, it’s a paraphrase of your comment.

i know sweetie, but you don’t put paraphrases in quotation marks — those are used when you quote someone verbatim

and apparently it’s a most egregious form of misconduct to have those two mixed up

In reply to Saša’s reply to Jazzlet, I ask Saša: You seem to know the basics of paraphrasing and quotation. If so, I have two questions: Is Senator Lindsey Graham’s paraphrase of your post an accurate representation of your position on plagiarism with respect to your original post? If not, would you care to correct any misrepresentation and, in the process, clarify your position?

in reply to Guititio: i guess it’s passable as a parody of my position on plagiarism. some clarifications are in order though.

in general: the textbook definition (six consecutive words or more) is useless. it can’t be strictly enforced (or like at least half of all the papers ever published should get retracted due to plagiarism), but it can be selectively applied. so i do believe that either (1) the textbook definition should be revised, or (2) ‘a reasonable amount of plagiarism’ should be permitted depending on the context. *especially* in humanities where thorough referencing and quotation would render the paper itself barely legible.

now in this particular case: again the Senator is kinda correct, i didn’t get all the facts nor will i. only made it through the first batch of emails RW obtained (the ones between Iloh and T&F) and caught enough red flags to conclude with enough certainty (for my standards) that there was foul play involved:

– the article was originally published in 2017, so let’s assume it was submitted in 2016 — a time when T&F was already using iThenticate to automatically screen submissions for plagiarism, and obviously no issues were raised at that time and the article got published

– on p33 of the PDF a similarity report overview for the paper is attached and it claims a whopping 48% similarity index which sounds like a reason to get the pitchforks out

– however upon further inspection of the similarity report overview we learn that only the bibliography filter was enabled — the ‘exclude quotes’ filter is off, meaning that even properly quoted passages got flagged; and you’d normally raise the match filter (not displayed in the report available here) to at least something like 20-ish or even more words in order to exclude as many false positives as possible and pinpoint only evidence of deliberate plagiarism

– all this is a sign of a sloppy and hamfisted investigation, and certainly not a ‘thorough’ and ‘careful’ review of plagiarism allegations and text overlap as T&F claim

– the fact that Iloh’s 2019 paper was flagged as a match *and* included in the original retraction notice that was later corrected is yet more indication that T&F’s investigation was anything but thorough and careful

obviously i’d need to see the full page-by-page similarity report to be absolutely certain beyond all doubt, but all of the above + all the correspondence between Iloh and T&F makes it likely enough that it was indeed a witch hunt so i’m inclined to trust her on this one

@saša marcan

“a reasonable amount of plagiarism’ should be permitted depending on the context. *especially* in humanities where thorough referencing and quotation would render the paper itself barely legible”

So where is the science, when one compiles someone else’s work and does not even bother to give credit?

@ mesh — i don’t know where the science is, but i see how plagiarism can happen without ill intent. you read something that sticks with you. you think about it a lot and end up internalizing it. years later you pass it off almost verbatim in your paper without realizing it’s something you read years ago. you don’t give credit because you believe them to be your own words.

or like if someone tells you a real good joke at the bar — if you retell it to your friends later, do you always give credit the person who told it to you originally?

Sarcasm is perfectly fine, even when the comment provides little of dialectic value, but the misogynistic “sweetie” used here is edging close to a slur and is entirely unnecessary. An f-bomb would be more professional than this. Please do better.

That said, the attempted defense of the plagiarism in this case (assuming it is reported even halfway accurately by the parties) is indeed laughable. At this level researchers surely must know the importance of citing primary and secondary sources, and it would probably behoove them to realize why grandiose threats of legal action are a great way to get negative RW coverage.

You’re communicating near-fluently in a second language, and yet unable to discern from context that we are not at present writing a scholarly paper intended for publication. Or is it the other way around–you think there’s no difference between shooting the shit in the comments section on a blog post, and authoring a work intended to serve as an authoritative reference or advancement of an academic field?

i really didn’t put that much thought into it. if you’re shooting the shit in the comments (and it felt that way to me) it’s only fitting that i clap back, right?

or do you feel that your comment was a genuine attempt at having a discussion or something?

The last two comments by Saša do not include a ‘reply’ button, but I understand that the absence of a ‘reply’ option is not the choice of the poster. So, note that the following comment is in response to Saša’s reply to my questions.

Saša, thank you very much for answering my questions. I just have one general comment: There does not exist a widely accepted operational definition of paraphrasing, that is, there is no official number threshold for what constitutes an acceptable paraphrase in the sciences nor, to my knowledge, in the humanities. I am aware that some authors who have written on the subject have recommended/suggested thresholds ranging from 3 words to 7 words (or perhaps 10, I now forget). But, I doubt that a numerical threshold for paraphrasing/plagiarism is used in any discipline.

As for how much text plagiarism (consecutive words from the original) should be allowed, I disagree with you that there should be greater tolerance in the humanities. No, instead, greater tolerance should be reserved for the sciences. Enclosing material in quotation marks is generally acceptable, even expected, in the humanities. Seldom, if ever, is there such an expectation in the sciences where many technical terms and expressions have no substitutes. In that regard, the definition of plagiarism offered by the US Office of Research Integrity, provides what in my view is the most reasonable guidance on text plagiarism (the material below was taken from https://ori.hhs.gov/ori-policy-plagiarism):

“As a general working definition, ORI considers plagiarism to include both the theft or misappropriation of intellectual property and the substantial unattributed textual copying of another’s work. It does not include authorship or credit disputes”.

“The theft or misappropriation of intellectual property includes the unauthorized use of ideas or unique methods obtained by a privileged communication, such as a grant or manuscript review”.

“Substantial unattributed textual copying of another’s work means the unattributed verbatim or nearly verbatim copying of sentences and paragraphs which materially mislead the ordinary reader regarding the contributions of the author. ORI generally does not pursue the limited use of identical or nearly-identical phrases which describe a commonly-used methodology or previous research because ORI does not consider such use as substantially misleading to the reader or of great significance”.

Based on the above, it seems to me that the textual lapses in the papers in question cross the line. You seem to disagree.

I’m not sure where you were going with that baffling feint.

Your basic premise seems to be “some plagiarism, especially in the humanities, is ok.” Let’s take it as true. Let’s even let you set the standard for it, which, I think, elsewhere you put at 60 words. And now we put you in charge of the International Court For Publishing-Related Lawsuits and ask you to adjudicate the following dispute:

A researcher claims he has been unfairly fired from his position because of an accusation of plagiarism. He and another coworker in the same company authored papers around the same time. They used almost the same sources, and the two papers are about almost the same topic–let’s say it’s different types of adult learners in American community colleges, and the different supportive strategies that work with each. Incredibly, both researchers were accused of plagiarism, but only one of them was fired. Both “used” two specific direct quotes without citation. The researcher who was fired used 65 words without citation in each instance. The researcher who wasn’t fired used 50 uncited words in the first instance (fair game), but 80 uncited words in the other. In the employer’s rationale, the fired researcher was twice the plagiarist as his counterpart. In the researcher’s rationale, he was half the plagiarist. He wants you to decide.

OK did you think about it? Do you have an answer? Is your judgment ready? Now recognize that there is no International Court For Publishing-Related Lawsuits and nobody wants to adjudicate this. Nobody wants to take the time to play weird games about acceptable lines and when they get crossed. It’s not a good use of time. Instead the broad scientific community operates, as others have pointed out, on a principle of trust, and this principle is backed in part by rigorous standards of citation, so that future researchers know what ideas and conclusions came from where. Therefore, researchers who just want to get on with things and not bother with the work of citation are violating that trust. No need to break out the calipers at all, it’s just not ethical or professional behavior to plagiarize.

Guititio: six consecutive words (unquoted, unattributed) is the widely/publishing industry accepted definition of plagiarism as evidenced by the cutoff point in the similarity report overview — there’s no flagged matches below that point; that’s the default setting in iThenticate with no filters. it’s cool if you think that sciences should be exempt from that and allowed more leeway — i think both sciences and humanities would benefit from a more lax definition of plagiarism instead of this one which can be selectively deployed against any author (but isn’t enforced by default).

again, i don’t know what the lapses were w/r/t the retracted T&F paper — for that i’d have to have access to the full similarity report.

Saša, thank you for the additional clarification. I must point out that whatever the cut-off number word sequence that Ithenticate uses in its algorithm has NOT, to my knowledge, been officially adopted in their definition of textual plagiarism by any national or international research integrity organization nor by any scientific or scholarly discipline, nor even by any of the major writing guides (Oxford, AMA, APA, MLA), or editors’ organizations (e.g., International Committee of Medical Journal Editors or the World Association of Medical Editors). Thus, my general sense is that to refer to a six-word cut-off as a widely accepted ‘textbook definition’ of textual plagiarism is, at best, misleading. After all, anyone could misappropriate substantial amounts of text from another source and simply ensure that every 5th or 6th word is changed/altered and call the resulting text original writing. Surely, you would agree that doing so would be plagiarism even if no single 6-word string or longer string from the original occurs in the newly ‘paraphrased’ version. Anyway, if I happen to be mistaken about any of this, I would appreciate very much if you or anyone reading these comments would provide us with a citation that contradicts any of the above.

Completely agree. That’s how it is with too many nowadays. They bend or break the rules, then whine and cry and blame you if you challenge it.

I haven’t finished reading the post either, so I might not have proper context for what you’re saying, but your comment really doesn’t make the case look as absurd as you seem to think it is.

>a few dozen missing quotation marks,

A FEW DOZEN? So there have been like 35+ instances of her misrepresentating other people’s text as her own? That alone is egregious, and it’s only the first item on your list of “what this boils down to”!

The root of the case is whole paragraphs lifted from others’ (and from her’s to), so bad enough and worthy of a RW report.

As for why the story staid on RW headlines for so long, well, that’s what one gets for trying hard to defend the indefensible and suing to prevent the release of embarrassing but releasable material. If she’d at least cut her losses and gone quietly, the story would now be buried deep into archives and essentially forgotten, but she chose otherwise and lost.

“If she’d at least cut her losses and gone quietly, the story would now be buried deep into archives and essentially forgotten, but she chose otherwise and lost.”

A form of Streisand Effect. But after reading her writings she seems to be one of those people I call a “professional victim”. Everyone is after her. Everyone is out to get her. Legal action will be taken! And all the rest. Even when it is apparent the paper in question has problems with attribution of material. It isn’t that she was sloppy with her work. It isn’t that she plagiarized material. It’s that everyone is after her. Everyone is out to get her. Legal action will be taken!

Quite frankly, if I were publisher/editor of the journal I would have dropped any attempt at communication with Iloh at the point she threatened “legal action”. Published the retraction as I saw fit. And let the “legal action” fall where it may. I wouldn’t have let this drag on for the months that it did. That’s for sure.

The problem here is the problem of trust. There is a strong expectation and requirement of honesty that underpins the scientific enterprise. When dishonesty (or a lack of honest representation of the truth) is observed this undermines the trustworthiness if the person. Yes, sometimes people are a bit sloppy, or the passage was written by a student, but repeated larger occurrences are an issue.

Her website is a mess of refusal to acknowledge shortcomings. There is an entire section dedicated to “mobbing and bullying” where she describes how “those adjacent to a particular academic context” had actually planned to kill her. This is a pretty clear sign of a professional victim. Her papers are barely science anyway, little more than opinions and conjecture and even then she couldn’t be bothered to correctly attribute sources. I don’t know what sort of silver spoon this person still has in their mouths but they clearly can’t handle being an adult. Crying and whining and throwing tantrums until people around you just give up is what 3 year olds do, not adult professional researchers.

The announcement of Constance Iloh’s position at Azusa Pacific University has been removed from the JBHE’s site linked in this post. The original article (archived here: https://web.archive.org/web/20221005211518/https://www.jbhe.com/2021/07/five-black-scholars-who-have-been-appointed-to-new-faculty-positions/) had the title “Five Black Scholars Who Have Been Appointed to New Faculty Positions”. The title has now been modified to “Four Black Scholars…”.

“The title has now been modified to “Four Black Scholars…”.”

__________

Constance Iloh’s name has been removed and the title of the article has been modified but the URL still says “five -black-scholars-who-have-been-appointed …” on the article that now only lists four.

You’d think if The Journal of Blacks in Higher Education were going to blackwash the situation for whatever reason they might have had they’d do a better job at it.

Perhaps someone with a little more clout could contact them and ask what’s up with Iloh and why they deleted her from the list.

https://jbhe.com/contact/

Not sure why it’s suspicious to remove the known plagiarist and fraud from a list meant to celebrate black academics. Are you asking for this kind of correction from every publication that published puff pieces on Elizabeth Holmes?