The scientific paper inspired international headlines with its bold claim that the combination of brain scans and machine learning algorithms could identify people at risk for suicide with 91% accuracy.

The promise of the work garnered lead author Marcel Adam Just of Carnegie Mellon University in Pittsburgh and co-author David Brent of the University of Pittsburgh a five-year, $3.8 million grant from the National Institute of Mental Health to conduct a larger follow-up study.

But the 2017 paper attracted immediate and sustained scrutiny from other experts, one of whom attempted to replicate it and found a key problem. Nothing happened until this April, when the authors admitted the work was flawed and retracted their article. By then, it had been cited 134 times in the scientific literature, according to Clarivate’s Web of Science — a large amount for a young paper — and received so much attention online that the article ranks in the top 5% of all the research tracked by Altmetric, a data company focused on scientific publishing.

All this could have been avoided if the journal had followed the advice of its own reviewers, according to records of the peer-review process obtained by Retraction Watch. The experts who scrutinized the submitted manuscript for the journal before it was published identified many issues in the initial draft and a revised resubmission. One asked for the authors to replicate the work in a new group of study participants, and overall, they recommended rejecting the manuscript.

The records also show the journal’s chief editor initially followed the reviewers’ advice — but then accepted the paper with some changes to its text, but no added data. The documents don’t explain the editor’s decision to publish, and a journal spokesperson declined to discuss the reasons.

“I was very upset,” said one of the reviewers, who asked to remain anonymous due to the sensitivity of breaking the convention of reviewer confidentiality. “Everybody knew this paper was garbage … and yet they went ahead and sent it out into the world.”

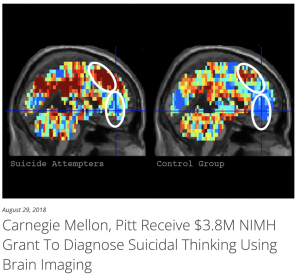

Just and colleagues’ manuscript began the peer-review process at the journal Nature Human Behaviour in early 2017. The paper described how the group used machine learning algorithms to analyze functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) scans of people’s brains and identify those at elevated risk for attempting suicide.

The researchers used fMRI to catch a glimpse of what happened in the brains of 79 young adults when asked to think about concepts such as “death,” “trouble,” “carefree,” and “good.” After excluding participants whose scans the scientists said had too much noise, they applied machine learning algorithms to the data from 17 of the people who had previously thought about dying by suicide, and 17 control participants who had not reported having suicidal thoughts.

Using a common method for testing the performance of algorithms, the researchers trained their system on the data of all but one participant, and then asked the model to predict whether the left-out participant had thought about suicide or not. They repeated this process until the model had made a prediction for each participant, and reported the model made the right call 91% of the time. Specifically, the algorithms correctly identified 15 of the 17 participants who had suicidal thoughts and 16 of the 17 controls.

Two of the three experts who reviewed the submission at the request of the journal called the reported accuracy “impressively high,” but offered detailed critiques of the work.

One reviewer called aspects of the methodology “concerning,” such as the authors omitting about half of their original sample of participants when testing their model in the paper’s main analysis. Even if those choices didn’t introduce bias into the model, the reviewer wrote, they indicated the approach was “likely limited” in its usefulness for the general population.

Another reviewer who detailed many concerns with the manuscript called for the authors to test their model on a separate group of people.

The other expert wrote that the paper’s results were “remarkable,” but asked the authors to address “several problems.” That reviewer wanted to see individual brain data included in the supplementary material, and for the authors to show more of their data that went into their statistical analyses.

Based on the feedback, Stavroula Kousta, Nature Human Behaviour’s chief editor, invited the authors to address the reviewers’ “quite substantial concerns” in a revision.

The authors did so, submitting the updated manuscript for another round of review by the two more critical experts.

One of the reviewers was not impressed, because the main analysis still focused on 34 participants “cherry-picked” from an original pool of 79, the reviewer wrote.

The other reviewer was initially more positive, because the revision clarified that the authors had used the same algorithms to evaluate scans of 21 of the participants who were initially excluded from their tests, and achieved an accuracy of 87%.

But in additional comments, that reviewer noted “several irregularities in the details” of the analysis of the excluded participants.

“These things make me a bit worried that some liberties are being taken to make the results better than they would be with a truly straightforward, unbiased replication of the findings in a new sample,” the reviewer concluded. “I would feel more comfortable with an independent replication in a new sample without the ‘fudge factors’ that seem to be present in this analysis.”

In July 2017, Kousta rejected the manuscript.

In the rejection letter, Kousta wrote that “we would be very pleased to consider a revision” if the authors performed an independent replication in a new sample of participants. “Without these data, however, the reviewers’ concerns with the present dataset & analyses are such as to preclude publication in Nature Human Behaviour.”

Yet in October 2017, the journal published the paper, without this additional data. The published version, however, describes the analysis of 21 of the participants who had been excluded from the main analysis, yielding 87% accuracy. The authors concluded these results demonstrate “the findings were replicated on a second sample,” thus “supporting the generalizability of the model.”

Soon after publication, experts took to Twitter to critique the paper for its small sample size and questioned whether the model could be broadly applied.In response to renewed criticism in 2019, an account for the journal tweeted that the paper was published “following thorough peer review because it provided important proof of concept for a potentially valuable method on a question of substantial clinical relevance.”

The authors retracted the paper this year after Timothy Verstynen of Carnegie Mellon University and Konrad Paul Kording of the University of Pennsylvania submitted a Matters Arising, a paper detailing their unsuccessful attempts to replicate the 2017 work with the code and data the authors had made available, and their concerns about bias in the model.

“While revising their response to these concerns, the authors confirmed that their method was indeed flawed, which affects the conclusions of the article,” the retraction notice stated. “The authors aim to demonstrate the predictive value of machine learning applied to fMRI data for the classification of suicidal ideators using new data and analyses in an independent future publication.”

In a statement, Just of Carnegie Mellon said they had discovered an “error in the statistical analysis” of the paper that “overestimated the strength of the main finding,” but “the main effect is present and clearly reliable.”

Just said the group was preparing a new submission describing the corrected results, and added the authors had notified their grants officer at the National Institute of Mental Health of the retraction. Their successful grant application included the findings described in their now-retracted paper.

A spokesperson for Nature Human Behaviour said that the journal “cannot discuss the specifics of individual cases,” but added that, in general, a paper’s authors can appeal the rejection of a submitted paper.

The journal’s editorial policies state that “decisions are reversed on appeal only if the editors are convinced that the original decision was an error.”

“I’m glad it only did six years worth of damage rather than 10 years worth of damage,” said the anonymous reviewer about the paper’s eventual retraction. “But it should never have been let out.”

This story was a collaboration between STAT, where it also appeared, and Retraction Watch.

Like Retraction Watch? You can make a tax-deductible contribution to support our work, follow us on Twitter, like us on Facebook, add us to your RSS reader, or subscribe to our daily digest. If you find a retraction that’s not in our database, you can let us know here. For comments or feedback, email us at [email protected].

In this age of doi’s and other persistent identifiers, it should be feasible to automatically propagate retractions to produce notices added to the citing papers. This should not be taken necessarily as something against the citing work, which may still be valid. But it is important that readers of the citing works are aware that the work being cited is retracted.

This is why I always find it very amusing when some people enthusiastically attack open-access journals for them being ‘predatory’. Who is really making huge profits by exploiting the academia? It’s those few giant publishers.

Thank you for this excellent reporting! One question: the article explains how the retraction is due to the “Matters Arising” piece published in Nature Human Behavior by Verstynen and Kording, which questioned the original article. Although the Matters Arising piece was published on April 6, 2023, it was actually received by Nature on September 1, 2020. That is an unusually long time between submission and acceptance/publication.

Did the authors do any review as to why it took Nature so long to accept and publish this piece? This case study could shed light into the internal process and discussions within a journal when the findings of a high-profile article published in that journal are called into question. As readers of this website know, some journals (not all) can be very slow to respond to information suggesting that a paper should be retracted.

Conveniently the grant (MH116652) that resulted from these data is in its last year. Since there (probably) wasn’t any foul play, unlikely that the NIH demands their funds returned. However, I doubt the PI will attempt to renew this grant.

“cherry picking data” = foul play?

that is academia, millions of tax payer funds are on the line for the data cherry pickers and manipulators.