Scopus is the world’s largest database of abstracts and citations, and calls itself “comprehensive,” “curated,” and “enriched.” But my recent experience with it suggests its curation could use some work.

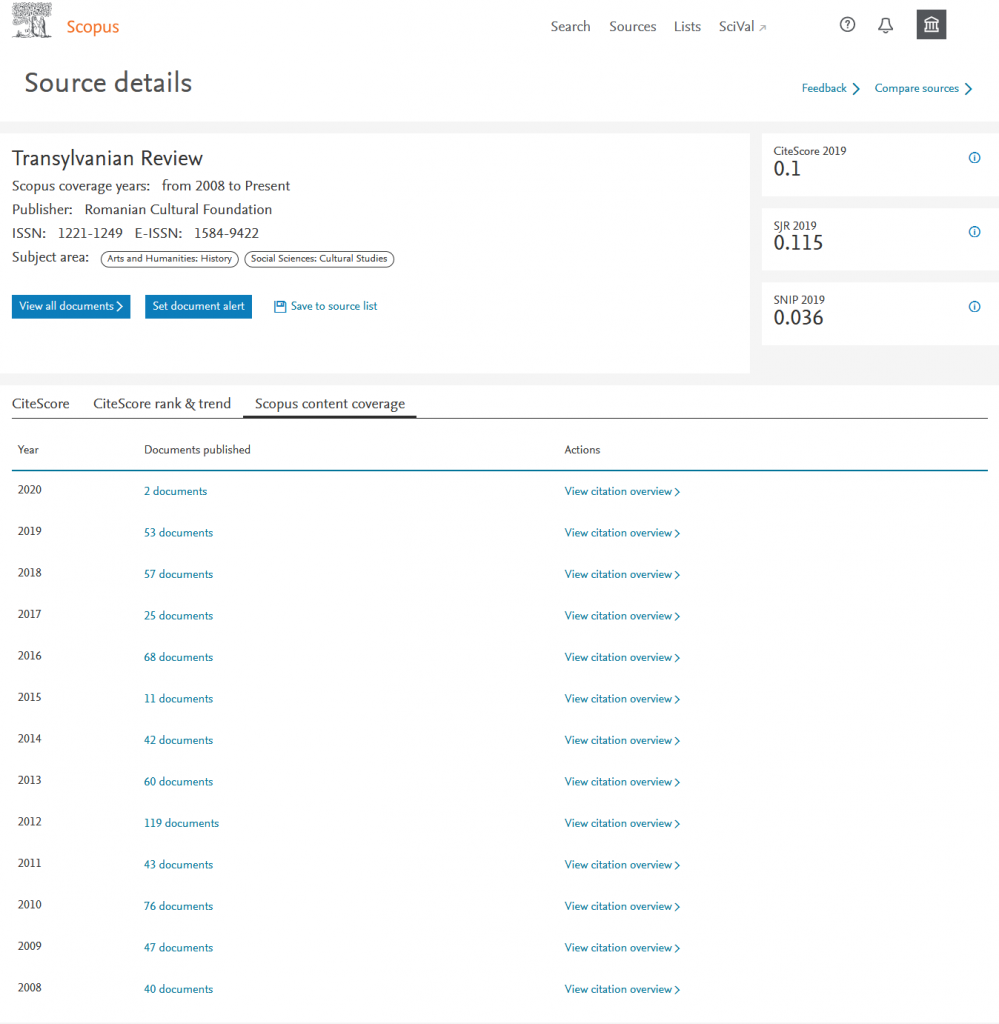

In October 2019, I discovered that the Scopus profile of the journal Transylvanian Review contained numerous faked articles. How did I know? A few years ago, a legitimate Scopus indexed journal, Transylvanian Review, was hijacked and listed on the well-known — but controversial — Beall’s List of predatory and unscrupulous publishers.

Many of these articles appeared on the cloned website and were authored by Iraqi researchers.

I decided to contact the Scopus support team to draw their attention on this matter. Praveena S, Content Service Desk, responded as follows:

I would like to thank you for the time in the investigation about the journal: “Transylvanian Review ” ISSN: 1221-1249E and providing us with a lot of details about its quality. As you aware that the journal is selected for the coverage in Scopus, but it has not made available online yet.

I can understand that you have been contacting us with your own interest and value towards the Scopus for its quality, so that I have requested the content selection board to re-evaluate the quality of the journal.

This Re-evaluation process will happen shortly and if they are found to be poor, the Scopus would surely discontinue the agreement. Also I have provided your contact details and if they require any update from your side, they may be contacting you.

I also contacted the publisher, Romanian Cultural Foundation, about this matter, but have had no response.

By July 2020, nothing had happened. That meant the CiteScore 2019 and earlier values for the journal were improperly calculated, as the faked articles were taken into account. I decided to contact Tracy Chen, the Scopus product manager, to follow up. She responded as follows:

Thank you for your feedbacks. I learnt from our colleagues this ticket was resolved and all content from the unauthentic sources have been removed. Will double check internally.

After 12 days, she wrote:

Thank you again for your feedbacks on unauthentic contents indexed in Scopus. We have processed the mentioned title and currently indexed content should come from the authentic website.

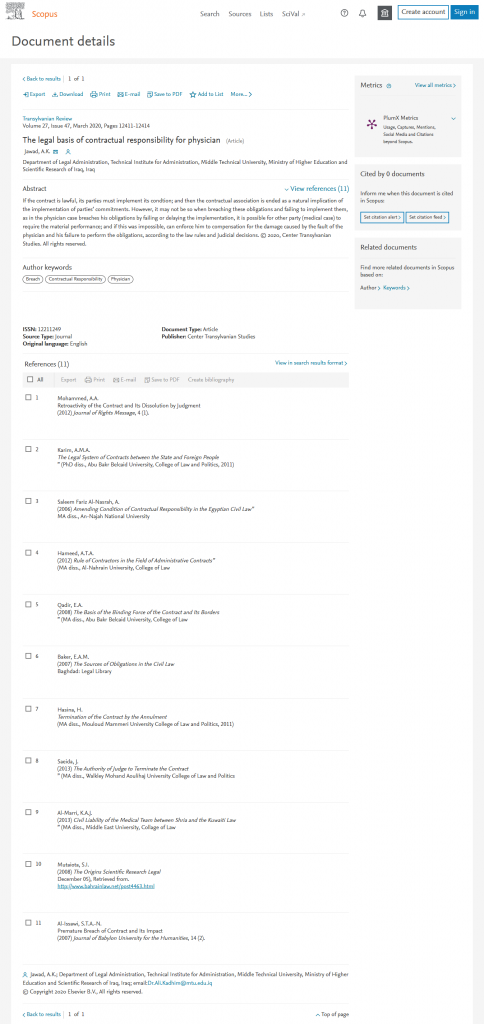

Meanwhile, I noticed that 112 articles published from 2018 to 2020 were removed from Scopus. A few days later, I discovered that a new faked article had been added to the database:

I contacted Chen again. This time, she wrote:

Thank you for your feedbacks. Really sorry for the slip. My colleagues will make sure this unauthentic paper will be removed.

The article was removed a few days later, but the database still contains many fake articles from this journal published in 2017 and earlier. It seems that Scopus managers are removing the contents of specific years rather than checking the indexed articles one by one.

It’s hard to believe that anyone can add faked content to the Scopus database so easily. I would urge Elsevier to reconsider this process, to ensure its reliability. Otherwise, it’s likely that we will see many such unfortunate cases in the future.

Mohammed O. Al-Amr is a lecturer in the department of mathematics in the College of Computer Sciences and Mathematics at the University of Mosul in Iraq.

Like Retraction Watch? You can make a tax-deductible contribution to support our work, follow us on Twitter, like us on Facebook, add us to your RSS reader, or subscribe to our daily digest. If you find a retraction that’s not in our database, you can let us know here. For comments or feedback, email us at [email protected].

I would blame the authentic Transylvanian Review, for this mishap as well.

Why? Are they somehow responsible for the fact that a gang of criminals set up their own website pretending to be the real journal?

Nobody question the evil deeds of those who hijacked legitimate journals

But, indeed, I think the authenticated journal shares the largest responsibility. Each journal should follow their indexed research in international databases such as Web of Science and SCOPUS. The journal should have recognized the fake content early on and should have alerted SCOPUS. This monitoring by the journal is essential to ensure the accuracy of SciScore calculations for the journal by SCOPUS.

Furthermore, by not monitoring its content, the journal contributed to the damage its reputations. Researchers who viewed the fake content over an extended of time, for sure thought negatively about the journal.

I think the real victims of this mishap are the poor Iraqi researchers who naively sent their manuscripts to the hijacked site. The appearance of the content on SCOPUS, further led other researchers to submit their manuscripts to the hijacked site. Other victims include the institutions and funding agencies who supported the research of those who were misled. I guess this created a big mess in these institutions

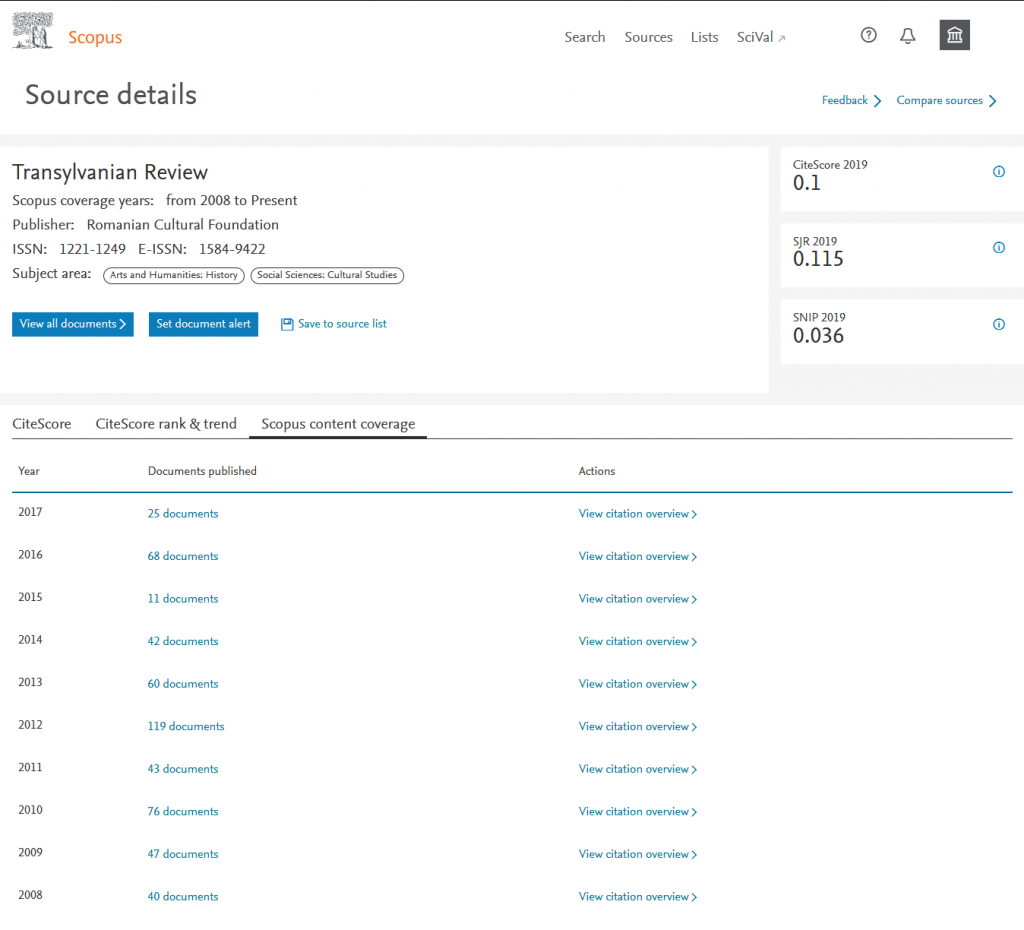

First of all, I would like to thank you for raising the issue of unauthorized content to be included in Scopus. As you will agree, journal hijacking a serious publication malpractice concern. Having unauthorized content from hijacked journals in Scopus is something that requires appropriate action and measures. However, this is also an issue that should not be taken lightly and requires deep investigation before judgements are made and actions can be taken. In the case of Transylvanian Review, it is unfortunate that it took more time than desired to have unwanted content removed. However, I hope you agree that I and my Elsevier colleagues have looked at your feedback seriously and kept you up-to-date on the progress. The screenshot in the post above does not reflect the current situation and as you have seen, all of the unwanted post 2017 content has been removed. In the meantime, we have also done an audit of the pre 2018 content in which 13 additional documents were identified to be removed, this to make sure all Scopus indexed content is from the authentic source.

Although I expect most journals would not have access to Scopus.

I was duped last year and after paying the publication fees, I had not received any further communication from the individuals who cloned the journal.

Last month I received another e-mail from the journal claiming to be legitimate – but it reflected a gmail account which made me suspicious. I sent an e-mail in response and then received a copy of my abstracts which seem to be on the legitimate journal page. I am still not sure what to do about this.

Find some piece of contact information (e.g. email address, phone number, mailing address) that you believe will still go to the legitimate journal, a member of the journal staff, an institution associated with the journal, or something else like that. Contact them using contact information you still trust; explain your issue in detail and ask for advice. Wait for a reply. Make sure you trust the reply (see below). Follow the directions in the reply. If any of these steps fail, your best course of action is probably to just accept that your publication fee is unfortunately gone and look for somewhere else to publish. You also try asking someone you trust at your institution for advice. It would also be good to report the fraud to relevant government agencies and service providers, but I don’t know how effective that will be: https://retractionwatch.com/2023/11/03/my-journal-was-hijacked-an-editors-experience/

Here are some signs that the reply is legitimate:

– It is labeled as coming from contact information you trust. Depending on the medium, there may be ways to verify that, such as email authentication headers.

– It is clearly a reply to your message (even automatic email quotation should be enough) and not just a generic fake reply.

– It doesn’t ask you to do anything risky, such as paying more money, signing an agreement, or giving them personal information. There could be legitimate reasons for these, but be very careful, and make sure you fully understand the potential risks.

It is sadly common for scammers to come back to their victims for a second bite of the cherry, claiming, under the guise of being in some position of authority, to be able to recover your money. At some point a fee will be charged for their time and expenses, of course. These “recovery scams” are well-known in other areas: look up, for example, the article “How recovery scammers trick vulnerable victims” from the UK consumer magazine “Which?”