When someone has to retract a paper for misconduct, what are the odds they will do it again? And how can we use that information to stop repeat offenders? Those are the questions that Toshio Kuroki of the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science and Akira Ukawa of RIKEN set out to tackle in their new paper, appearing in Accountability in Research. Not surprisingly, they found that people with multiple retractions are more likely than others to have another — and when people have at least five retractions, the odds are significantly higher.

Retraction Watch: Why did you decide to examine the chances of researchers retracting additional papers?

Toshio Kuroki: The retractions related to problems with prominent stem cell papers (STAP) and the cardiovascular drug by Novartis (Diovan) that happened in 2014 prompted me to write a book in Japanese entitled “Research misconduct” for the general public. By the recommendation of Nature Japan, this book, which appeared in 2016, is now being translated into English and will likely be published by Oxford University Press in 2019.

In writing on this theme, Retraction Watch (RW) is a very useful source of information. I was much shocked by the Retraction Watch leaderboard, which showed three Japanese names are listed among the top 10 people with the most retractions. I wonder why they repeatedly retract their publications. There must be some habitual misbehavior in research practice.

Our study was further extended to Web of Science (WoS) and PubMed, and analyzed by Dr. Akira Ukawa, a particle physicist and vice director of RIKEN Advanced Institute for Computational Science.

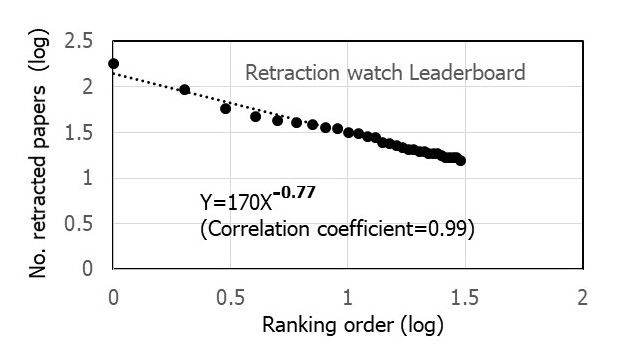

RW: You note that retractions follow the “power law.” Can you explain what that is, and why knowing it is useful?

TK: Power law is a mathematical model applicable to a wide variety of physical, biological, and social phenomena which distribute over a wide range of magnitudes: these include magnitudes of earthquake, sizes of craters on the moon, citation of scientific literatures, funding to universities, the latter of which I found. Power law implies signature of hierarchy, suggesting that retraction is a stochastic phenomenon with some rules behind, rather than a random event.

When I see a sequence of numbers, I often try to find some rules behind these numbers. Putting numbers in Excel and clicking several times, we will get a graph and an equation within a half hour, which implies some mathematical rule exists behind the phenomenon we observed.

When I saw the Retraction Watch leaderboard, I noted by intuition that the sequence of retraction numbers is most likely to follow a power law. And I found this is the case by converting these values to logarithms and plotting them on a double log paper. Thus, although each retraction occurs independently, in whole it is governed mathematically by power law.

I estimated repeating probability on the basis of power law. However, Dr. Ukawa, with whom I have been working for the WPI program (a flagship research program of the government), calculated it using much more sophisticated mathematical model.

RW: You found that 3-5% of authors with one retraction had to retract another paper within the next five years– but among those with at least five retractions, the odds of having to retract another paper within the same time period rose to 26–37%. In some ways, these findings aren’t too surprising, as people with a history of problems could see effects in multiple papers. Did anything about the findings surprise you?

TK: Power law is also called as “preferential attachment” or “rich-get-richer,” which means observed differences have a tendency to be amplified. In the same way, it can be said that “retraction makes more retraction.” It is, therefore, not surprising to know that retracting authors with multiple retractions are more likely to have repeat retractions than those with a single retraction.

RW: As our leaderboard shows, there are some people who have an extremely high number of retractions — particularly Yoshitaka Fuiji, an anesthesiology researcher with more than 180 retractions. Most researchers — even those found guilty of misconduct — retract only a few papers. Do outliers such as Fuiji and people with dozens of retractions impact or skew your analysis?

TK: Outliers with extremely high numbers of retractions such as Y. Fujii with 180+ retractions and J. Boldt with 96 are listed in RW. This is the reality. Unlike normal distribution, power law analysis can be applied to data with a large range of distribution, so outliers have no significant impact in power law.

RW: You write: “By focusing on those with repeated retractions, this analysis could contribute to identification of measures to reduce such repetition of retractions.” How might your findings be used to reduce additional retractions? People with multiple retractions are likely already being watched closely by their peers — what else can be done?

TK: A researcher is shocked and normally feels guilty when his/her paper is retracted. However, those with multiple retractions may be insensitive, and not recognize what they are doing.

Therefore, the most important thing is to identify authors with multiple retractions and recognize their bad practice. There must be some habitual background allowing bad practice of research: manipulation of gel-images may be routinely carried out and students are not taught that it is a bad practice. In some laboratories, students are forced, by harassment, to make up data. Researchers in such cases should be advised by colleagues, university authorities or administration offices including funding agencies.

But multiple retractions can be seen in different environments– one with a poor monitoring system, and the other with a well-established system.

In Japan, we were so naïve in research misconduct, allowing such terrible cases, Y. Fujii and S. Kato (I used to work in the field close to the area of Kato and know him well, but fortunately no collaboration). After the STAP affair, science communities as well as the public in Japan are more aware of this problem, which we hope will result in a reduction in misconduct.

Like Retraction Watch? You can make a tax-deductible contribution to support our growth, follow us on Twitter, like us on Facebook, add us to your RSS reader, sign up for an email every time there’s a new post (look for the “follow” button at the lower right part of your screen), or subscribe to our daily digest. If you find a retraction that’s not in our database, you can let us know here. For comments or feedback, email us at [email protected].

I am happy there are people actually focusing in this issue. I hope it will eventually incorporates also de academic/corporate pressure to publish; the fact that the pharma companies celebrate dodgy contracts where the labs are only paid if they provide certain specific results; and/or whereas careers of these researchers are put on the line if they don’t publish in the current dogma of the area. Note how publishers and editors also “gang up” on researchers that provide contradictory or simply “out-of-the-box” to standard research as well as some undisclosed/shaddy conflict of interests between journals/editors/senior authors. Early career researchers face an atmosphere of sabotage and stalling for publication specially when not backed up by some senior “known” names. Sadly, most reasons for researchers to commit misconduct are all ultimately based in social and peer-pressures, thus in human “group” behaviour on itself !

Students and/or posdocs that stand up against misconduct practices are subjected to bullying and shunning/outcasting.

I would be interested to see a breakdown between people who have multiple retractions of work that was published before their first retraction (i.e., where an investigation showed how much they had been getting away with for years), and those who are forced to retract an article but get a “second chance”, then go on to publish new stuff that is also fraudulent, and end up having to retract that too. I’m guessing that if people do survive in science after being caught cheating that some of them may “go straight”, although it must be pretty hard after scoring all those easy results to suddenly start actually running the marathon rather than getting into a cab after a mile.

This is a very useful question, Nick. I think that one obvious part of an explanation for the observation of the power law in operation is that when institutions, external bodies, or whistle-blowers discover a serious offence against Responsible Conduct of Research they feel obliged (or even instinctively impelled) to investigate further and bring additional resources to the follow-up investigation(s). The Stapel investigation is a clear example of this multiplier effect in the “how much they had been getting away with for years” category.

Harder to chart the “blew the second chance” category but, in a way, this would be the really interesting one to investigate. From non-systematic observation, I can dredge up a very small number of examples. I suggest it would have to include papers submitted after the date of the *finding* of misconduct rather than the date of the earliest retraction to avoid picking up work that was part of the “old practice” and already in the pipeline; it would also enable account to be taken of the sometimes lengthy delays in papers actually being retracted!

I agree that serial misconduct is not a random event, but is a power law.

My understanding of misconduct comes from my training and experience of child development. Small children are only right brain (creative) thinkers. Unfortunately, most of our socialising/schooling is left brain (logical) thinking thus is incomprehensible and inappropriate to the child below the age of 7-8. Since logics is about yes/no production, most people at a young age develop tactics to give the right answer (such as cheating, copying, or rote memorisation) without any comprehension. These solutions become ingrained subconscious behaviours and frequently remained used throughout life. There is a saying, ‘when the subconscious and conscious come into conflict the subconscious wins every time’, particularly under stress. Very dysfunctional people can becoming very cunning (creative) in pretending to know, especially if they are rewarded because they can provide a Yes. Ethics and other considerations then become subordinate to the yes/rewards.

Under such conditions of sufficient stress, competition, poor training, and poor control/regulation nearly everyone will produce a random act of misconduct. The serial misconductor however thrives in such conditions because he has learnt how to beat the system, remain unobserved, and reap benefits (possibly such an environment may attracted others producing a group mentality; a toxic collective). Such people can rise to the top, even becoming major ‘power’ players of the ‘law’ like presidents.