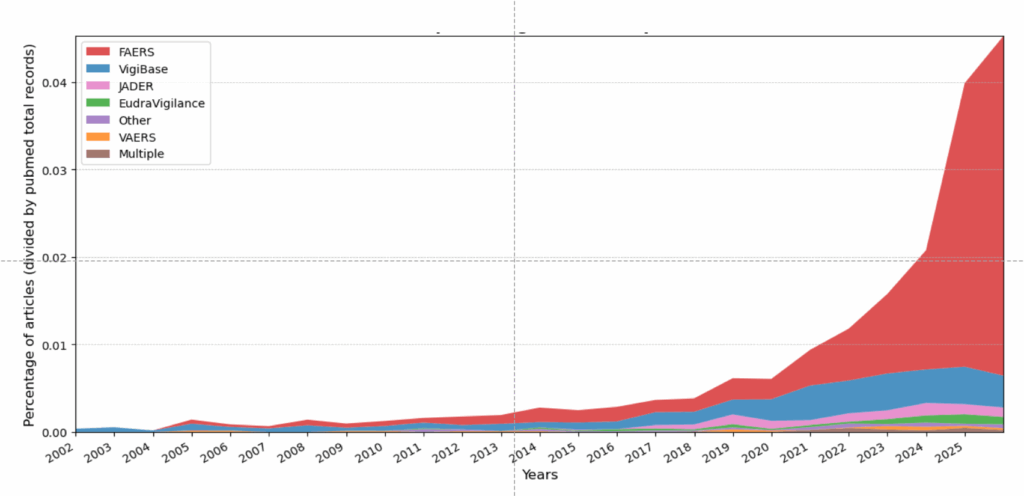

Starting around 2023, a curious trend took hold in papers on drug safety monitoring. The number of articles published on an individual drug and its link to specific adverse events went from a steady increase to a huge spike.

The data source in most of those articles was largely the same: The FDA Adverse Events Reporting System, or FAERS. In 2021, around 100 studies mining FAERS for drug safety signals were published. In 2024, that number was 600, with more than that already published this year.

Two journals in particular published the bulk of these papers, Frontiers in Pharmacology and Expert Opinion on Drug Safety. In response to the flood, Frontiers started to require independent validation of studies drawing on public datasets. And Expert Opinion on Drug Safety decided in late July to stop accepting submissions altogether that use the FAERS database for this particular type of study.

“By presenting mere statistical associations as ‘safety signals’, these publications can generate unjustified alarms with considerable impact on healthcare provider practices and patient behaviors,” Charles Khouri, a pharmacologist at Grenoble Alpes University Hospital in France, and colleagues wrote in a preprint posted Sept. 14 that looks at the spike in pharmacovigilance studies.

Source: C. Khouri et al. 2025

The work comes on the heels of sleuths identifying FAERS as one of several publicly available datasets being exploited by paper mills, pumping hundreds of often meaningless and sometimes misleading papers into the scientific literature.

An open database, FAERS contains 31.8 million records voluntarily submitted to the FDA by healthcare professionals, patients and consumers on adverse events and medication errors related to drugs and biologics. While the database is useful flagging adverse events from newly approved drugs, it can be misused as a research tool.

“You can imagine in a large database with maybe millions of different drugs, millions of different adverse events, you can perform an infinite number of statistical analyses,” Khouri told Retraction Watch.

FAERS is a voluntary reporting system, so “only an unknown proportion of all adverse events are reported,” Khouri said. And factors like a drug’s novelty or media attention can affect whether people report adverse events.

That same selectivity and voluntary reporting structure affects the data in the Vaccine Adverse Event Reporting System, or VAERS, jointly managed by the FDA and CDC. Health secretary Robert F. Kennedy Jr. has vowed to overhaul VAERS, even as those campaigning against the use of vaccines publish papers — often retracted — using it. News outlets have reported that Trump administration officials plan to present VAERS data later this week linking COVID-19 vaccines to at least 25 deaths in children who received the shots. As with FAERS data, raw reports in VAERS are unconfirmed, and any associations between an injury and a vaccine may be coincidental.

The FAERS papers flooding the journals are a type of study called a disproportionality analysis, which can identify previously unknown side effects to drugs following their approval. “Maybe 60 to 70 percent of modifications in label information after the commercialization of drugs are coming from a pharmacovigilance database like FAERS,” Khouri said.

Khouri pointed to a disproportionality analysis of a diabetes drug called pioglitazone that found a possible increased risk of bladder cancer. Further studies corroborated the risk and ultimately led to labeling changes for the drug.

From 2019 to 2022, Expert Opinion on Drug Safety published single- to low double-digit numbers of these studies. That began to change in 2023 and exploded in 2024, when the journal published 174 disproportionality studies using FAERS, nearly 60 percent of the total papers it published that year – and as many papers as they had published in total in 2021.

The number of disproportionality studies submitted to the journal “rose significantly,” a Taylor & Francis spokesperson told us. “Even after we had put additional resource[s] in place to handle the journal’s pre-review assessments, this had become a challenging situation to manage,” the spokesperson said. “While disproportionality studies can make a useful contribution to the scholarly literature, such papers can include methodological problems, which led to the journal having a rejection rate of over 80%.”

In late July, Taylor & Francis and the journal’s editor-in-chief, Roger McIntyre, professor of psychiatry and pharmacology at the University of Toronto, decided “the journal will no longer consider unsolicited disproportionality studies using [FAERS] or similar spontaneous reporting databases,” the spokesperson said.

The journal’s website now states, “Such studies will only be considered when specifically invited by the journal’s editorial team.”

Two requests for interviews sent to McIntyre’s university email address were answered by Taylor & Francis spokespeople. McIntyre, who is also the head of the Mood Disorders Psychopharmacology Unit at Toronto’s University Health Network, is a coauthor on five articles in Expert Opinion on Drug Safety that draw on data from FAERS. They include analyses of associations between insomnia drugs, ketamine or GLP-1 agonists and suicide.

In August the journal retracted a paper based on FAERS for including a coauthor on the paper without his consent. “While no other disproportionality studies are currently under investigation by our Publishing Ethics & Integrity team, we are conducting further checks on several articles in the journal,” the spokesperson said.

Frontiers in Pharmacology also contributed to the flood of published studies drawing on FAERS. The journal published about 30 such studies in 2023 — and more than 120 in 2024.

In May 2025, Frontiers introduced a policy across all of its journals requiring “independent external validation of all health-dataset studies,” Elena Vicario, head of research integrity at Frontiers, told us. The move followed a July 2024 policy requiring that validation for submissions using Mendelian randomization methods. “The concern is not the use of FAERS itself but the risk of redundant analyses that add little new scientific understanding,” Vicario said.

Frontiers in Pharmacology has since updated its About page to reinforce this policy, Vicario said. “Since July 2024, 739 FAERS submissions to Frontiers in Pharmacology have been rejected, with 9 published since the updating of the author guidelines in 2025.”

The bolus of newly published FAERS papers have some notable characteristics, Khouri has found, in collaboration with computer scientist and sleuth Cyril Labbé, also at Grenoble Alpes University, Emanuel Raschi from the University of Bologna, Alex Hlavaty from the University of Grenoble, and others.

For example, nearly 80 percent of these studies published in Expert Opinion on Drug Safety between 2019 and 2025 are from authors affiliated with institutions in China. “Chinese authors were totally absent from the field before 2021,” Khouri said.

An analysis of the papers in Expert Opinion on Drug Safety revealed a few authors on multiple articles. At the top of the list is Bin Wu of Sichuan University in Chengdu, who has published 27 disproportionality studies based on FAERS, seven of which appear in Expert Opinion on Drug Safety. Li Chen, also of Sichuan University, has six papers in the journal, and Wei Liu of Zhengzhou University, is a coauthor on at least four studies. Neither Wu, Chen or Liu responded to emailed requests for comment on their field of study, or particular interest in the FAERS database.

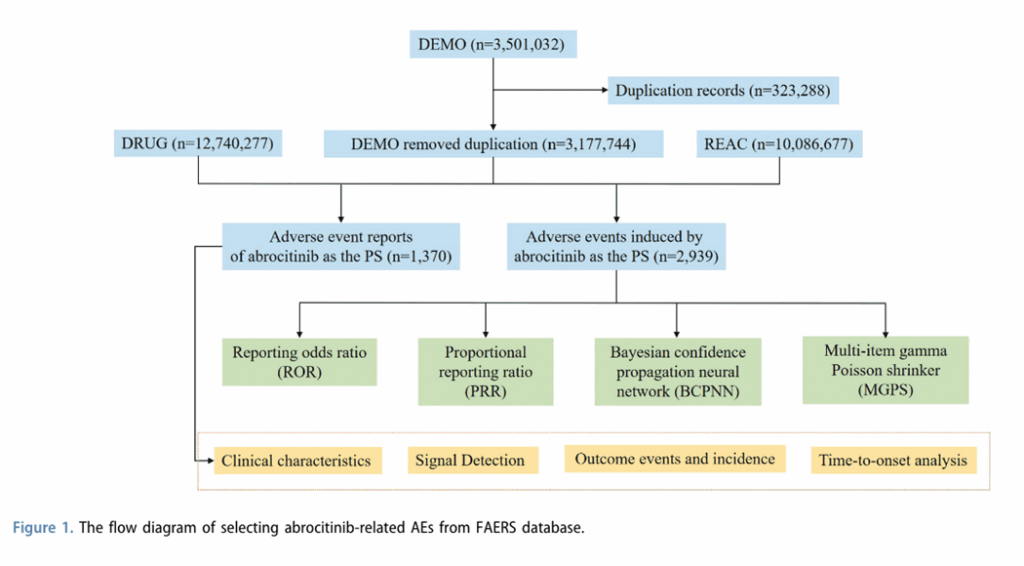

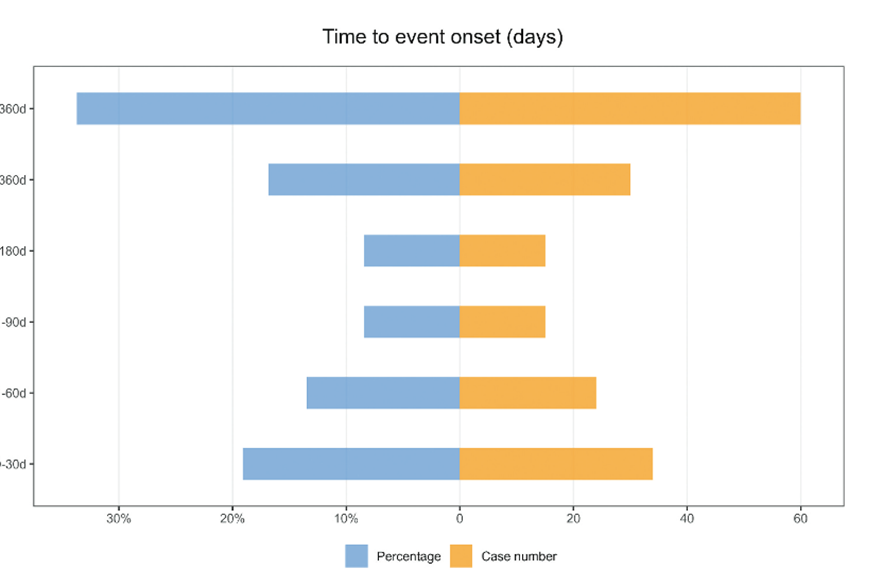

Many of the recent papers use multiple statistical methods for the disproportionality analysis, whereas researchers typically use only one method, because multiple tests are redundant. Other similar features across recent papers include a flow chart showing how data were selected, and a mirror plot showing “time to onset.” “We never saw that before,” Khouri said. “The information is quite useless to be twice plotted in the same figure.”

And another shared feature of the recently published disproportionality analyses: “There is no research question,” Khouri said.

Many of the studies also reflect a lack of understanding of the drugs and conditions being described. As an example, Khouri pointed to a paper finding a link between sildenafil and pulmonary hypertension as an adverse event — when in fact the drug is prescribed for that very condition.

Open databases like FAERS paired with the rise of generative AI have opened up a new era of automated paper generation by paper mills, posits Matt Spick, a lecturer in data analytics at the University of Surrey in England. In a July 9 preprint posted to MedrXiv.org, he and colleagues recently identified five databases with anomalies in publishing rates that might indicate paper mill exploitation. Among them: FAERS.

That analysis built on an earlier study Spick did that showed a rapid rise in single-association studies published between 2021 and 2024 that drew on another open data source, the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, or NHANES. While the analysis cannot attribute the increase to paper mills specifically, it offers a case study of a strategy paper mills may use, the authors wrote in a paper published in May in PLOS Biology.

“Once NHANES went online, as a paper mill, you were no longer being slowed down by your ability to acquire data, or copy images. You could download as much data as you wanted,” Spick told Retraction Watch.

The flood of papers coming out of these open databases, and FAERS in particular, can waste research dollars if investigators launch studies to validate the signals generated in these studies, Khouri said. And, importantly, these studies can also influence doctors and patients. “We know that when there are safety warnings disseminated in the literature, patients can stop the drugs,” he said. “Prescribers can be influenced by this kind of result, presenting a lot of adverse events for the drugs.”

Aside from the August retraction, only one other paper based on FAERS data has been retracted. The disproportionality analysis had appeared in BioMed Research International and was pulled as part of Wiley’s cleanup of suspected paper mill activity and manipulated peer review in Hindawi journals.

That statistic wasn’t surprising to Khouri. “It’s very difficult to retract these articles for fraud, because there is no fraud,” he said. “The results are nonsense, there is p-hacking and high risk of false results. It’s useless papers, but they are not fake,” he said, quickly adding: “Probably.”

Khouri’s next steps are to dig further into patterns across these papers to see if they can identify common features. And Spick has been working on picking apart precisely how paper mills might use modern technology, including LLMs, to scrape open databases like FAERS and churn out papers at scale.

“It will be hard to force retractions for a lot of these, and then it becomes a whole philosophical thing for meta-scientists,” Spick said: “Should we allow all science to be published, even if it’s meaningless?”

Like Retraction Watch? You can make a tax-deductible contribution to support our work, follow us on X or Bluesky, like us on Facebook, follow us on LinkedIn, add us to your RSS reader, or subscribe to our daily digest. If you find a retraction that’s not in our database, you can let us know here. For comments or feedback, email us at [email protected].

If eighty percent of the problem papers come from the same country, the solution is simple.

That particular country again. Doing their best at gaming a system they didn’t create but eagerly want to participate.

“The bolus of newly published FAERS papers have some notable characteristics”

An admirable word choice: “a small round lump of a substance, especially partly digested food”.

“— Spick said: ‘Should we allow all science to be published, even if it’s meaningless?'”

Definitely yes.

Given the peer review crisis, LLMs, and other related issues, I think the journal business is slowly grinding to a halt anyways.

For these and other reasons, what was once a niche practice (arXiv) is nowadays mainstream.

What is needed in this new situation is different gatekeeping than the broken prestige game. A good starting point would be to again, you know, actually read papers. The alternative publishing models, such as overlay journals, might offer another alternative.

I don’t think we should condemn a country just because there are many FAERS reports like this. Many doctors are compelled to do this due to inadequate review systems. These aren’t cases of academic misconduct; the research findings merely indicate potential risks and serve as a reminder for medication safety. It’s just that too many people are doing itIn reality, the country lacks any real say in the matter, and this article may actually be discriminatory.

Except there are no research findings. Just p-hacking, data dredging and boilerplate text as far as an eye can see.

Thank you for your interest in the fears database mining. I am Liu Wei from Zhengzhou University, as mentioned in the article.Unfortunately, I did not see and promptly respond to the relevant email mentioned in the article earlier. This maybe because the email was mistakenly flagged as spam and automatically routed to the spam folder. As a researcher who has been utilizing the FAERS database for adverse drug reaction research since 2020, I ‘d like to share my opinion. Firstly, as the biggest open database of adverse drug reactions globally, the FAERS database has very important research value. Like all databases, the more researchers use it, the more its value can be fully recognized. Secondly, I disagree with completely halting research on the FAERS database. While it’s undeniable that the number of studies based on this database has significantly increased over the past two years, this doesn’t mean its scientific value should be entirely dismissed. In my view, a more feasible approach is to implement stricter review mechanisms, such as focusing during peer review on whether studies pose clear scientific questions, employ scientifically sound research designs, and yield conclusions with significant clinical implications. Furthermore, all relevant research should be cross-referenced with product labeling information, and any potential risk signals discussed should be supported by a sufficient number of reports to enhance their reliability and reference value. And thirdly, since publishing our first paper in 2021, my team has released seven research findings related to the FEARS database over the past four years with an average of about two papers per year. These papers represent the collective efforts of seven different graduate students. Our research focused on comparative studies of adverse reaction signals from similar drugs or drug combinations, aiming to help physicians and pharmacists identify certain adverse reactions not yet mentioned in drug labels earlier, enabling timely clinical intervention and enhancing drug safety. Furthermore, we also hope to explore how to individualize drug selection for patients with the same disease but different physiological characteristics, thereby minimizing the risk of adverse reactions. I’ve been contemplating whether adverse reaction databases could not only alert to risks but also provide recommendations and references for “positive selection” in clinical medication practices! Of course, we strongly hope pharmaceutical companies will pay attention to and validate these signals, and promote updates and improvements to drug labels through further research. Finally, we will continue our research and continuously refine our methodologies, such as integrating real-world data and other multi-source information to enhance the reliability and clinical translation value of our findings. We also warmly appreciate and look forward to receiving valuable feedback and suggestions on our previous research work. Thank you!

In several instances, there have been publication of disproportionality analyses (DPAs) AFTER publication of analytical epidemiologic studies, in which case the DPAs are pure wastage of time and attention. The FDA in its pharmacovigilance guidance characterizes DPAs as “signal generating,” which may identify a need for an epidemiologic study that measures risk, not anecdotal reporting.

Free speech should be banned. Certainly, a privatized journal is within its bounds to ban speech even if it’s not disinformation or fraudulent. Everyone knows that medications don’t have side effects, only profit margins. And besides, the newer medications that interfere with or modulate inflammatory or immune responses can only be associated with fewer adverse effects, so we can eventually expect decreased reporting anyway. Only researchers associated with the NIH, who can control other countries’ scientific endeavors, and who can recognize the lack of risk (e.g., no risk from COVID-19) should oversee access to information. I applaud the journal overseers for the lack of discrimination in their blanket ban.

Epic trolling of a seemingly corrupt and increasingly irrelevant scientific publication system. Love it!

Very well said!!!

Finally someone with a backbone. However, this opinion probably will self destruct when the authors of this paper actually read the comment section.

While these studies have several limitations due to the limitations of the database itself, they still hold importance to the field of pharmacovigilance if done appropriately by expert groups. A classic example of using the database occurs when clinician-scientists observe repeated safety issues or adverse events in patients on a specific class of treatment. In such cases, the database is mined for the disproportionality of the particular side effect of interest. If the database reveals disproportionality consistent with clinical observations and the link is plausible, further studies to investigate this biologically plausible association using well-designed cohort studies are encouraged. These studies by no mean provide information on risk or incidence, rather they alert the community to look further into a potential signal for an association. Banning these studies altogether may not be the right solution; rather, careful evaluation of the studies and critical feedback to the authors to improve their work would move the field of medicine forward.

This “careful evaluation of the studies and critical feedback to the authors to improve their work would move the field of medicine forward” may be correct but, to use the jargon from this field, it is not a “real world” solution. The tsunami of publications far exceeds the time and energy of competent referees to filter out the large proportion of useless contributions. As an expert in serotonin toxicity I warned about this some five years ago when papers started producing spurious associations about drugs that could cause ST — most of the editors for whom I reviewed papers simply published the stuff anyway. Many of these contributions are not based in science or pharmacology and pay no heed to mechanisms or cause-effect relationships. Perhaps we should all pay more attention to the words of Professor Pearl (causal science Guru), who said “data are profoundly dumb about causal relationships… without causality science is nothing”