Thirty-four medical professional societies have called for The BMJ to retract a recently published guideline recommending against the use of interventional procedures, such as steroid or anaesthetic injections, to treat chronic back pain.

The journal published the guideline in February as part of its Rapid Recommendations program alongside a meta-analysis and systematic review of published research on the procedures, which the guideline panel used to inform its recommendations. The publications received international news coverage and enough chatter on social media platforms such as X and Bluesky to place them in the top 5 percent of all articles scored by Altmetric, a data company that tracks digital mentions of research.

The societies, led by the International Pain and Spine Intervention Society, represent clinicians who prescribe or perform the interventional spine procedures the guideline recommends against. The groups “have serious concerns about the methodology and conclusions drawn in these publications and their potential impact on patient care,” they wrote in a statement dated March 18, and summarized in a rapid response on the BMJ’s website. The statement has since been published in The Spine Journal and Interventional Pain Medicine.

The authors of the guideline and meta-analysis have stood by their work in responses to the critiques and comments to Retraction Watch. The BMJ “have no plans to take further action” beyond publishing the critiques and authors’ responses, Caroline White, a spokesperson for the journal, told us.

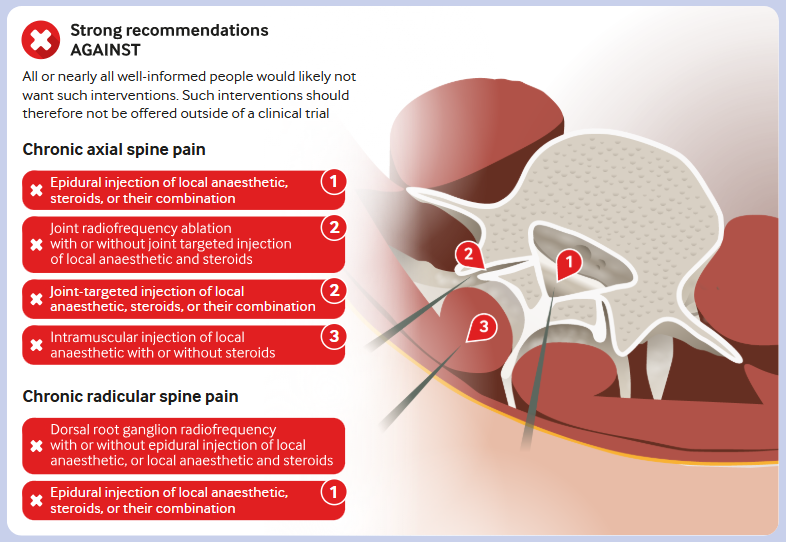

The systematic review included 132 previously published trials, of which 81 yielded data for the meta-analysis. The authors found “no commonly performed interventional procedure provided convincing evidence of important pain relief or improvement in physical functioning,” they wrote. “Indeed, in many instances the evidence showed moderate certainty of little to no effect.”

After reviewing the findings, the guideline panel, which included some of the authors of the review, “concluded that all or almost all informed patients would choose to avoid interventional procedures” for chronic spine pain, they wrote, “because all low and moderate certainty evidence suggests little to no benefit on pain relief compared with sham procedures, and these procedures are burdensome and may result in adverse events.”

The guideline authors speculated “the substantial reimbursement associated with these procedures may act as a perverse incentive” for their use.

In an editorial accompanying the articles, Jane C. Ballantyne of the University of Washington School of Medicine in Seattle noted some existing guidelines on the procedures recommended their use, while others recommended against them. Ballantyne, an anesthesiologist and pain medicine specialist, had served as a peer reviewer for the systematic review and meta-analysis before publication, according to The BMJ’s open review documents.

The new publications, she wrote: “will not be the last word on spine injections for chronic back pain, but it adds to a growing sense that chronic pain management needs a major rethink that is perhaps best achieved by a better balance of reimbursements between procedural and non-procedural chronic pain treatments.”

The radiology and pain medicine societies detailed several critiques of the work in their letter asking The BMJ to retract the guideline, “based on extensive clinical experience and a review of the evidence.” The meta-analysis inappropriately combined data from trials of different procedures in patients with different diagnoses and areas of spine pain, they wrote, which “allowed pooling of data at the expense of interpretable conclusions.”

The guideline, in turn, lumped together “disparate groups of patients, conditions, spinal regions, and procedures,” they wrote. “Conflating these groups in analysis is convenient but misguided; in guideline development, it is misleading and irresponsible.”

The guideline also drew on studies of techniques that are no longer used, left out studies the medical societies deemed important for supporting the benefit of the techniques, and inaccurately extracted data from another positive study, the statement claimed.

Joshua Rittenberg, president of the International Pain and Spine Intervention Society, posted summaries of the letter on The BMJ’s website as rapid responses to the guideline and meta-analysis. He acknowledged the interventional procedures “are not universally effective,” but argued they could help “appropriately selected patients.” Rittenberg did not respond to our request for comment.

In responses to the critiques, Jason Busse of McMaster University in Hamilton, Ontario, and coauthors disputed the assertion the meta-analysis had included studies on procedures not commonly used in practice, and denied excluding any eligible trials. They also defended their method of pooling data, as subgroup analyses they conducted “found no evidence for systematic differences in treatment effects” for different spinal regions, procedure approaches, or conditions.

“We are aware that our findings are disappointing to clinicians that administer interventional procedures for chronic spine pain, and have carefully considered all Rapid Responses submitted to the BMJ,” Busse and Liang Yao, the corresponding authors of the guideline and meta-analysis, respectively, wrote in comments to Retraction Watch.

“If some clinicians believe that they can correctly identify patients with chronic spine pain who will benefit from interventional procedures, we believe they should undertake high quality sham-controlled trials to provide evidence,” they wrote. “As we note in our guideline, such evidence would alter our recommendations.”

Like Retraction Watch? You can make a tax-deductible contribution to support our work, follow us on X or Bluesky, like us on Facebook, follow us on LinkedIn, add us to your RSS reader, or subscribe to our daily digest. If you find a retraction that’s not in our database, you can let us know here. For comments or feedback, email us at [email protected].

A someone who’s had a spinal injury, the meta analysis seems on point. Any medical interventions i tried had no effect other than the side effects of the intervention.

Even better than a meta-analysis is an anecdote powered by N of 1.

“Thirty-four medical professional societies have called for The BMJ to retract a recently published guideline recommending against the use of interventional procedures, such as steroid or anaesthetic injections, to treat chronic back pain. ”

You forgot to mention those thirty-four medical professional societies calling for the retraction have clear conflict of interest in that society members livelihoods (ie. income) directly depends on continuing to provide these “medical interventions” to patients even though there is apparently no clear benefit in doing so in the long term.

Third paragraph:

The societies, led by the International Pain and Spine Intervention Society, represent clinicians who prescribe or perform the interventional spine procedures the guideline recommends against.

I totally agree

Pain medicine is a scam operation

The author quoted in this article (Jason Busse) is a chiropractor in Canada…who has the conflict of interest now? He’s not even an MD or DO.

really?

All Author’s list:

Xiaoqin Wang, methodologist, Grace Martin, MD anesthesia resident, Behnam Sadeghirad, assistant professor, Yaping Chang, assistant professor, Ivan D Florez, professor, Rachel J Couban, medical librarian, Fatemeh Mehrabi, doctoral student, Holly N Crandon, MBiotech candidate, Meisam Abdar Esfahani, MSc candidate, Laxsanaa Sivananthan, MD candidate, Neil Sengupta, MD candidate, Elena Kum, PhD candidate, Preksha Rathod, MD candidate, Liang Yao, assistant professor, Rami Z Morsi, neurology resident, Stéphane Genevay, rheumatologist, professor, Norman Buckley, anesthesiologist, professor emeritus, Gordon H Guyatt, general internist, distinguished professor, Y Raja Rampersaud, orthopedic surgeon, professor, Christopher J Standaert, physiatrist, associate professor, Thomas Agoritsas, general internist, associate professor, Jason W Busse, professor

The end of the article says it all, essentially doctors that do not provide interventional Pain Management need a higher level of reimbursement. What a self serving piece of garbage this was.

The original article was patently absurd. It suggests that treatments that need to be Repeated every 6 to 12 months are useless because they are not permanent. An article written mostly by physiatrist who don’t provide this kind of care and would probably recommend repetitive hot and cold packs and ridiculous Repetitive rounds of physical therapy.

Ask any patient who has received profound, albeit limited duration relief from interventional procedures, and you will find a profoundly grateful patient. Talk to a patient who had severe radiculopathy and received Months of pain control from a simple, five minute procedure and you’ll find another person who finds the original article to be absurd. The idea that we should not provide medical care of any kind that does not provide permanent relief of the condition to be treated is also simply absurd.

Not unlike many of the other social catastrophes noted in the UK as a direct result of their absurd recent decisions, this article would lead to complete chaos in the Chronic Pain world. But I’m sure the physiatrists there have a great long-term plan for these chronic pain patients. I’m sure the plan will include lots of physiatry and extensive use of narcotics.

Wow. I’m sorry you’ve had such poor experience with physiatrists. There are several factual inaccuracies to your comment. Physiatrists can absolutely provide spinal interventions and undergo fellowship training to do so alongside anesthesiologists. Of the authors listed above, only one is specified as a physiatrist. Other specialties who contributed to this article include orthopedic surgery, anesthesia, neurology, and rheumatology, but you have chosen to direct all your ire towards physiatry. Singling out physiatry leads me to believe you have had a poor interaction. I can’t speak for the training and care of all physiatrists, but as a board certified physiatrist who has also participated in residency training, I can speak to several facets of it. if you would like to have an open conversation about the care, skill, and value a physiatrist can provide to a patient, I’ll happily engage, when I’m not busy explaining detailed anatomy to a patient (evidence based care for low back pain), injecting Botox (FDA approved for spasticity management), or evaluating gait and balance to decrease fall risk and associated comorbidities (research shows increased mortality risk with hip fracture). I sometimes even refer patients with acute radicular symptoms preventing them from being able to engage safely in basic ADL’s to my interventional colleagues for directed injections. And I haven’t written an opioid prescription in years.

This article has many drawbacks. Arguably the largest is that insurance companies will undoubtedly use it to deny care to suffering patients. But they win when physicians are pitted against each other, which is exactly what is happening here.

I had a back injury several years ago. Surgeon wanted to operate, pain management doc wanted to inject my spine. A physiatrist management me conservatively and in 3 months I am 100%. Thank you.

Most interventional pain procedures are not meant to be “permanent fixes” to chronic spinal pain. The authors seem short term relief as a failure of care? So the alternative is what? Narcotics instead of injections?

It’s true that a lot of providers perform unnecessary procedures for revenue purposes but don’t lump all of us in that group. My success rate with injections is extremely high and I have been able to keep numerous patients off opiate medications.

Original article is shortsighted

Are we really at a point in medicine where we accuse specialists of malpractice for personal gain? I remember several years ago when a poorly designed study declared kyphoplasty a worthless procedure. Those of us on the front lines who provided daily compassionate care using our best judgement suffered the fallout from this carelessness. I had to spend more time on peer-to-peer calls listening to insurance industry paid “professionals” tell me they were looking forward to vertebroplasty being declared “useless” too. Until you’ve repeatedly seen a post vertebroplasty or kyphoplasty patient stand for the first time in months without pain and smile with joyful tears, you just can’t throw out careless criticisms. The BMJ doesn’t care about the criticism – their article gets global attention. The only useful response is canceling BMJ subscriptions and question their authority on current and future publications.

Ortho PA here. On top of temporary relief for patients who do not want or cannot have spine surgery, we use epidural steroid injections to confirm that more aggressive surgical intervention, like a microdiscectomy/fusion, will work. What shows up on MRI and what patient feels does not always correlate with the exact level. Better to trial and error with an injection than spine surgery.

Pain Management is certainly not a “curative” specialty. It is a palliative specialty. If repeated interventional procedures provide enough even temporary relief to allow patients to avoid surgery, especially repeated surgeries, and opioid dependence in cases of intractable benign chronic pain it is a worthwhile tool.

Meta-analyses are fraught with complications. If you have a group of high-quality studies on similar patients, sure, combine them and draw meta-conclusions. But the data are all mixed, with crap methods, and then you end up with this undrinkable grey water that contaminates all understanding of what might work and for whom. It’s a literal coup to downgrade the most rigorous science to null effect.

The message I get from this is that we still need more and better research to show what procedures help or don’t help what patients. My personal experience, from having several bouts of sciatica over many years, with multiple MRI abnormalities, is that epidural steroid injections didn’t help, but core strengthening and stretching exercises introduced by physical therapists and a physiatrist did help. Part of making America healthy should be emphasis, from an early age, of whole body physical fitness as a lifetime necessity.

True, epidural steroid injections do not always help, but in properly selected patients, they do. I completely agree that core strengthening and stretching are helpful, and should be done by everybody, that also has its limitation. I am a nationally competitive rower that can do 60 leg lifts at a time, dead lift 235 pounds, and I do a 2k on a Concept 2 in 7 minutes. My core was/is plenty strong, yet before my facet radiofrequency ablations in 2023, my back was screaming after sitting in a chair for about 10 minutes. By 20 minutes, I had to get up and walk around. Facet blocks completely alleviated that for the rest of the day, and radiofrequency ablation lasted a year on the right, and it has now been a year and a half on the left with no recurrence. Absolutely life changing. And yes, I still row, and barefoot waterski. I just do it without back pain now.

Meta-analysis. A way for people who don’t do research to get published. It’s amazing how this analytical nonsense got so widely accepted so quickly in medicine.

I consider getting a hug from a grateful patient as evidence of the efficacy of an appropriately selected and performed spinal injection procedure.

Regarding the methodology utilized by the authors of the BMJ article, I would ask whether there exists any double-blind study to validate the efficacy of parachutes for someone electively or emergently jumping out of an airplane.

Meta analysis=garbage. Come out with a real study otherwise don’t waste time.

As a neurosurgeon and competitive rower with multiple US National Championships at the Masters level, I can assure all who are reading this that facet (median branch) radio frequency ablation absolutely works wonders IF you improve with facet blocks. I went from being unable to sit more than 20 minutes to being able to tolerate sitting indefinitely now. I could not drive more than 20 minutes without pulling over to walk around the car. I could not row more than 20 minutes without laying back in the boat to stretch. And the breaks didn’t allow another 20 minutes. The time between breaks gets shorter and shorter. It turned a 2 hour car ride into 3. I seriously considered giving up rowing because of the back pain, but if i didn’t row for a couple of weeks, the back pain with sitting got worse, not better. I could not sit through a whole meal at a restaurant. I’d stand behind the chair and lean on the back of it to stay in the conversation at the table, or sometimes eat standing up. I had bilateral facet radiofrequency ablation at the end of 2023. I rowed 14k in a single 2 hours after the procedure with no back pain at all. I repeated only the right side at the end of 2024 for recurrence of symptoms only on the right. Those symptoms have been nearly gone since then. It aches a little now if I sit for long periods, like on a long flight, but nothing I can’t handle with a little position change in the seat. No more sharp stabbing pain. Totally life changing. My core was already, and still is, amazingly strong from rowing, and surgery was not necessary for facet degeneration with no neurologic symptoms. To recommend against offering facet radiofrequency ablation to someone like me is almost criminal. This is as bad as previous junk “studies” claiming kyphoplasty does not work for compression fractures, and microdiscectomy for radiculopathy is no better than medical management.

As an interventional physiatrist with 20 years of experience performing epidurals and other pain procedures, I see the positive results from these procedures every day. Read some of my reviews and tell me the injections don’t work.

Interesting – what journals are your reviews published in?

As an Emergency specialist who has had the reluctant job of prescribing addictive narcotics to patients with chronic back pain, and one with multiple herniated disc who has had years of relief from steroid injections himself. I say those who doubt the benefits from such injections should walk in my shoes.