A year after the authors of two papers contacted the marketing journal where they had been published requesting retraction, the journal has pulled one, but decided to issue a correction for the other.

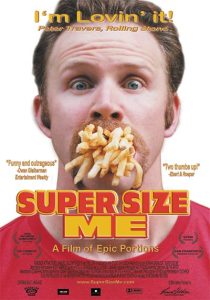

In April, we reported that the Journal of Consumer Research was investigating “Super Size Me: Product Size as a Signal of Status,” originally published in 2012, and “Dynamics of Communicator and Audience Power: The Persuasiveness of Competence versus Warmth,” published in 2016.

The authors had asked to retract the papers in October 2022 after other researchers found inconsistencies in the statistical calculations of the “Super Size Me” paper and could not replicate the results. The article had been cited nearly 200 times, according to Clarivate’s Web of Science. It attracted attention from The New York Times and NPR, among other outlets, which linked the findings to the rise in obesity in the United States. An analyst also found issues in the 2016 paper, which has been cited 71 times.

When we published our previous story, Carolyn Yoon, the chair of the journal’s policy board and a professor of management and marketing at the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor’s Stephen M. Ross School of Business, told us the board was still waiting on a report from the special committee investigating the matter. “We hope to have a decision by the end of this month,” she said in April 2023.

In June, the journal published expressions of concern for both articles (which continued to be cited). Both notices stated:

On October 22, 2022, the journal’s Policy Board received information about problems with the data in this article. We alert readers that the Policy Board’s assessment is ongoing. In the interim, we advise them to exercise caution when interpreting the data, results, and conclusions in this article.

On October 29 of this year, the journal retracted the “Super Size Me” paper and published a correction to the other article. The policy board also published a note about the two articles that stated:

It was the initial understanding of the Journal’s Policy Board that after the authors identified methodological issues with both articles in 2022, they disagreed about how best to address them and asked the Policy Board, which comprises organizational representatives appointed by its sponsoring organizations, to determine how to proceed. In the interim, Expressions of Concern were published in June 2023.

The 2012 article has since been retracted at https://doi.org/10.1093/jcr/ucad055. A correction to the 2016 article has also now been published at https://doi.org/10.1093/jcr/ucad056.

The Policy Board thanks the investigative committee members for their handling of the latter case.

The retraction notice read:

This article is being retracted following the discovery of a set of statistical errors in studies 1 and 6, which cannot be explained as the authors no longer have the data. Given these errors, the authors concluded that the claims of the paper are significantly challenged, and the authors no longer have confidence in the results as reported. The authors state that the hypothesized link between power and consumption deserves future empirical consideration before the field draws any firm conclusions about this relationship.

There is empirical evidence, available upon request from the authors, that the results from study 1 can be replicated and that reexamination of the data for study 3 replicated all the results initially reported.

The correction notice acknowledged that two of the paper’s three authors, Derek Rucker of the Kellogg School of Management at Northwestern University in Chicago and Adam Galinsky of Columbia Business School in New York City, had requested a retraction. The investigative committee recommended a correction, instead. The notice stated:

Reexamination of the data in the article by the investigative committee revealed a newly discovered series of irregular data patterns. None of the tests performed through the reexamination of the data were considered or performed by the authors at the time of publication, and the authors were unaware of these patterns at that time. Of note, reexamination efforts found that test statistics reported in the article were replicable.

None of the omissions in the experimental design were intentional. As the sole individual responsible for data collection, processing, and analysis, the first author assumes full responsibility for the inadvertent lack of communication regarding how the data were collected.

The rest of the notice detailed a mismatch between the data for one experiment and the results in the paper, reported a corrected statistical value, and explained how “the description of the experimental procedure unintentionally omitted important design elements that could mislead readers.”

David Dubois, now a professor at the Fontainebleau, France campus of INSEAD, is the first author of both articles. We emailed him for comment and received an auto-reply that he had “very no email access” and to expect a “significant delay” in getting a response.

Rucker told us:

Adam and I don’t have a comment about either the 2012 or 2016 paper. We requested retraction of both papers, and we no longer endorse either paper. However, we also agreed to abide by whatever decision JCR made after their investigative process.

We asked Yoon about the length of the investigation, and she told us:

I don’t have any comments beyond what’s stated in the notes accompanying the retraction and correction. We applied due process in accordance with the journal’s policies.

The investigative committee’s work took a few months to complete. And then everything else including all communications back and forth with authors, policy board, and the publisher took many more months.

Aaron Charlton, who maintains OpenMKT.org, a site aimed at improving evidence quality in academic publications in marketing and consumer behavior, was among the researchers who identified issues in the studies and informed the authors of his findings. Last July, he left a comment on our story about the journal’s investigation that said they had decided not to retract the articles.

We asked him what seemed to have changed, and he told us:

My understanding of the retract/don’t retract fiasco is this: JCR policy committee had decided not to retract either article. I pointed out that it was ridiculous that they would refuse to retract an article at the authors’ request. Many others agreed. Then, JCR decided they would honor the authors’ request. They now claim that they didn’t know the authors were united in asking for the retraction of the 2012 article and they thought their purpose was to adjudicate between the authors. Hence the decision not to retract initially. I guess they didn’t think it was super important, so they didn’t take their time to gather all of the facts before making their decision.

Charlton also said:

I’m not super happy with the outcome. Literally all of their communications with the public have been hostile toward whistleblowers and deferential towards the data anomalist. For example, in the retraction statement they point out that the anomalist got the study to replicate but they fail to mention that an independent third party failed to replicate the study (which is what initiated this whole thing really). Who cares if a data anomalist claims they can replicate their own (now retracted) paper? What about source credibility?

I am familiar with the forensic analysis of the 2016 paper, which JCR says is fine. The paper is not fine. Much more information is forthcoming on this. Some of the analysis has already been leaked. Keep in mind that the other two authors both requested retraction of the data due to unexplainable data anomalies that massively supported the hypothesis.

This is not JCR’s only problem. Only one JCR study has ever been successfully replicated by an independent third party. 28 attempts to replicate JCR papers have failed. I maintain the replication tracker for the field of marketing here: https://openmkt.org/research/replications-of-marketing-studies/ They may claim that if you change a thing here or there you can get a study to replicate but I only count exact replications. If you try to exactly replicate a JCR study you can expect to run into difficulty as 28 out of 29 other replication teams have.

Like Retraction Watch? You can make a tax-deductible contribution to support our work, follow us on Twitter, like us on Facebook, add us to your RSS reader, or subscribe to our daily digest. If you find a retraction that’s not in The Retraction Watch Database, you can let us know here. For comments or feedback, email us at [email protected].

Marketing journals are full of questionable articles – see one such below

Biology and being green: The effect of prenatal testosterone exposure on pro-environmental consumption behavior published in Journal of Business Research.

One can easily make it out that if this paper was viewed under stringent statistical lens it will fail to pass the statistical smell test. Shameful that reviewers and editors did not do their due diligence